Mysteries of Udolpho

Mysteries of Udolpho

On Friday I made the claim that zombie movies provide young people with a way to react against the numerous stratagems that our society uses to manipulate them, whether through advertising or celebrity hype or political appeals. What I said about zombie movies could also be applied to Twilight and Harry Potter and other fantasies. These stories give young people powerful ways to forge identities in the face of social pressures that are (to put it mildly) daunting.

In the late 18th century, young people turned to gothic novels for the same reasons. I was reminded of this as I picked up Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, which I begin teaching tomorrow.

But Jane Austen offers a follow-up insight that I should have mentioned. While she has no problem with young people reading such books, she feels that, at some stage, they need to grow past them. If you’re still stuck on zombie movies when you’re 30, there’s a problem.

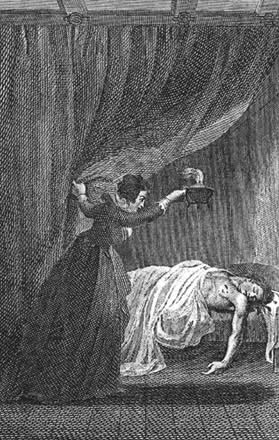

The young ladies in Northanger Abbey are enthralled with the novels of Anne Radcliffe, which address adoescent concerns no less than do contemporary gothics. In The Mysteries of Udolpho and The Italian, young, unmarried women were able to see versions of their own confinement. In real life, they were closely chaperoned and forbidden to venture out by themselves. They were also hedged in by scores of rules and restrictions. Life, as a result could get very boring.

In Radcliffe’s novels, it’s not mom and dad and the vicar and the village gossips who are hemming the heroines in. Rather it is mad barons and crazy stepmothers and scheming monks. The jailer may be a member of the Spanish Inquisition, who in The Italian abducts the heroine and carries her off in a closed coach across the Alps. The books make confinement exciting.

In fact, one feminist scholar has pointed out how Radcliffe’s lush descriptions of nature–freshly fallen snow in an Alpine pine forest glistens in the moonlight–turn abduction into a travel fantasy. At least young readers got to escape dull and boring England in their imaginations.

Furthermore, the female heroines, while they are victims, have a certain amount of agency. They creep around their prison fortresses at night uncovering dark secrets.

Austen makes the point that Catherine Morland must learn to distinguish between fantasy and reality. In other words, she must learn to grow beyond the gothic to, say, the kind of fiction that Austen would go on to write. When she suspects that General Tilney has done away with his wife and shares her suspicions with his son, he jolts her out of her paranoid speculations with a humiliating reproof:

If I understand you rightly, you had formed a surmise of such horror as I have hardly words to—–Dear Miss Morland, consider the dreadful nature of the suspicions you have entertained. What have you been judging from?

Catherine’s eyes are opened:

Charming as were all Mrs. Radcliffe’s works, and charming even as were the works of all her imitators, it was not in them perhaps that human nature, at least in the midland countries of England, was to be looked for. . . . [I]n the central part of England there was surely some security for the existence even of a wife not beloved, in the laws of the land, and the manners of the age. Murder was not tolerated, servants were not slaves, and neither poison nor sleeping potions to be procured, like rhubarb, from every druggist. Among the Alps and Pyrenees, perhaps, there was no mixed characters. There, such as were not as spotless as an angel, might have the dispositions of a fiend But in England it was not so; among the English, she believed, in their hearts and habits, there was a general though unequal mixture of good and bad. Upon this conviction, she would not be surprised if even in Henry and Eleanor Tilney, some slight imperfection might hereafter appear; and upon this conviction she need not fear to acknowldege some actual specks in the character of their father, who, though cleared from the grossly injurious suspicions which she must ever blush to have entertained, she did believe, upon serious consideration, to be not perfectly amiable.

So Catherine, in gaining perspective on her fantasy works, at the same time steps into the maturity of an adult. But Austen has one more surprise for us. The General suddenly starts acting irrationally and, in a total violation of protocol, orders Catherine out of his house. (The reason, we learn later, is that he suddenly discovers, or so he thinks, that she has less money than he previously thought.) As a result she must return home, unaccompanied, in a carriage. For the age, this is a big deal.

In a stab at the patriarch, Austen lets us know that, while the gothic may be fantasy, the issues it addresses are serious. Women are indeed victimized by family patriarchs. Upon learning the reasons for the General’s behavior, Catherine realizes that she hasn’t been as mistaken as she thought:

Catherine, at any rate, heard enough to feel, that in suspecting General Tilney of either murdering or shutting up his wife, she had scarcely sinned against his character, or magnified his cruelty.

So we should take seriously the fantasy stories that young people are drawn to. Often they are fighting for their sense of self in a world that does not have their best interests at heart. And while they should move beyond Twilight and Harry Potter and zombie movies, they should do so only because good adult fiction will give them a deeper understanding of the forces they are up against. They need all the resources they can get in their battles.