Friday

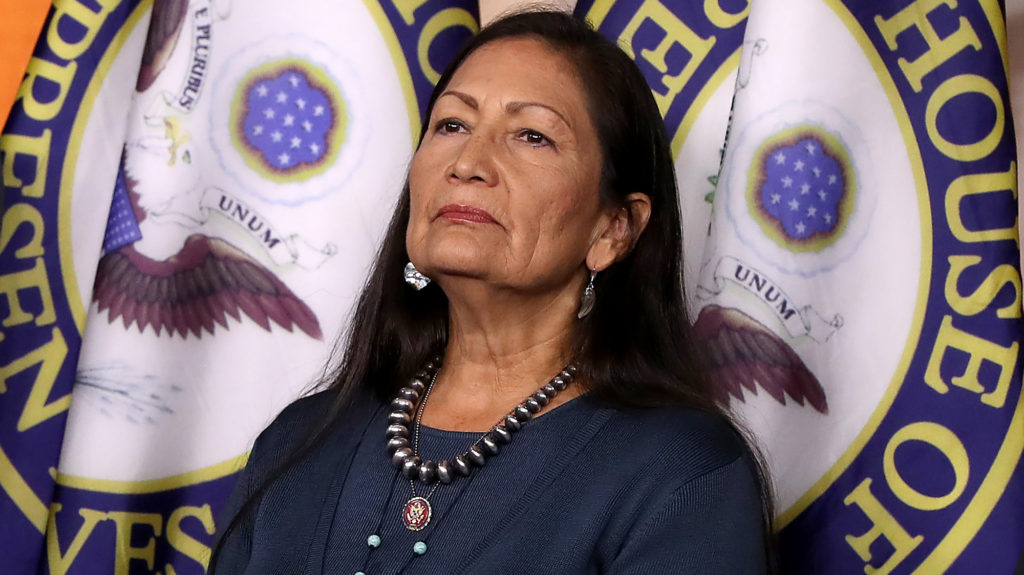

I see that Rep. Deb Haaland, who has just been confirmed as Secretary of the Interior (she’s our first Native American Cabinet Secretary), is a member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe, which is also Leslie Marmon Silko’s tribe. If Haaland’s vision of the environment is anything like that of the acclaimed novelist, which I believe it is, then America’s public lands are in good hands.

Silko’s Ceremony is my favorite Native American novel. In it, Silko describes a sickness overtaking America as it grows away from the land. Her protagonist, a World War II veteran who has survived the Bataan Death March, must reconnect with the earth if he is to overcome his own fragile mental state, brought about by mother abandonment, childhood bullying, PTSD from his war experiences, survivor guilt, white racism, and Indian prejudice against his mixed race. The odds are formidable but, by tapping into tribal ceremonies (thus the novel’s title) he finds a way forward, both for himself and for the planet at large.

I’ve written several times (including here) about Silko’s vision of the “witchery” that she believes is destroying the planet. Her poem about a witch’s prediction of a white invasion pretty much captures the Trump administration’s vision of the environment, including its desire to sell off and desecrate public lands:

Then they grow away from the earth

then they grow away from the sun

then they grow away from the plants and animals.

They see no life

When they look

they see only objects.

The world is a dead thing for them

the trees and rivers are not alive

the mountains and stones are not alive

The deer and bear are objects

They see no lifeThey fear

They fear the world.

They destroy what they fear.

They fear themselves.

In search of cattle that whites have stolen from his uncle, Tayo finds them on land that was once used by Indians and that has now been fenced in to keep Indians out. This sets off a reflection on what the whites have lost in thinking they can own the land:

If the white people never looked beyond the lie, to see that theirs was a nation built on stolen land, then they would never be able to understand how they had been used by the witchery; they would never know that they were still being manipulated by those who knew how to stir the ingredients together: white thievery and injustice boiling up the anger and hatred that would finally destroy the world: the starving against the fat, the colored against the white. The destroyers had only to set it into motion, and sit back to count the casualties. But it was more than a body count; the lies devoured white hearts, and for more than two hundred years white people had worked to fill their emptiness; they tried to glut the hollowness with patriotic wars and with great technology and the wealth it brought. And always they had been fooling themselves and they knew it.

And further on:

The [Indians] had been taught to despise themselves because they were left with barren land and dry rivers. But they were wrong. It was the white people who had nothing; it was the white people who were suffering as thieves do, never able to forget that their pride was wrapped in something stolen, something that had never been, and could never be, theirs. The destroyers had tricked the white people as completely as they had fooled the Indians, and now only a few people understood how the filthy deception worked; only a few people knew that the lie was destroying the white people faster than it was destroying Indian people. But the effects were hidden, evident only in the sterility of their art, which continued to feed off the vitality of other cultures, and in the dissolution of their consciousness into dead objects: the plastic and neon, the concrete and steel. Hollow and lifeless as a witchery clay figure. And what little still remained to white people was shriveled like a seed ohoarded too long, shrunken past its time, and split open now, to expose a fragile, pale leaf stem, perfectly formed and dead.

Grim though this picture is, Ceremony wrestles though to a positive conclusion, with Tayo providing a model for healing. His quest acknowledges our need for a healthy environment, solid relationships, and meaningful work. When he returns with the cattle, which are environmentally friendly (they can survive in barren environments), he gives the elders reassurance that the young will carry on tribal traditions. Their wisdom has guided him and he will ensure that the old customs continue on. There’s a balance between young and old, continuity and change, and nature and humans that bodes well.

While Haaland may not be able to undo all the damage wrought by the Trump administration, let alone all that Indians have suffered over the centuries, she has those issues in her sights. According to a Red River Radio article,

She’s promising to begin repairing a legacy of broken treaties and abuses committed by the federal government toward tribes. It’s one pillar of a long and ambitious to-do list of reforms the administration is planning at the sprawling agency that is the federal government’s most direct contact with the nation’s 574 federally recognized — and sovereign — tribes.

And:

Nationwide, tribal leaders believe the injustices of the past might start to be reversed under Haaland. The Biden administration has indicated it’s reinstating an Obama-era rule requiring consultation with tribes, meaning that any future lands development or right of way projects like pipeline must be signed off on by affected tribes.

No one is expecting miracles, but Haaland’s appointment represents an important step. As Silko makes clear, it’s not only the future of Native Americans that’s at stake.