Tuesday

Yesterday, after seeing a Sewanee student production of Hamlet, I compared Claudius’s successful coup to Donald Trump’s attempted one. Today I’m thinking of the play again after having read a Washington Post article about political turmoil in a polarized Montana town. Not only are the adults fighting about today’s hot button issues but, over the past 16 months, nine of their teenagers have committed suicide, including three since the beginning of the school year. Hamlet’s own suicidal thoughts help us understand what may be going on.

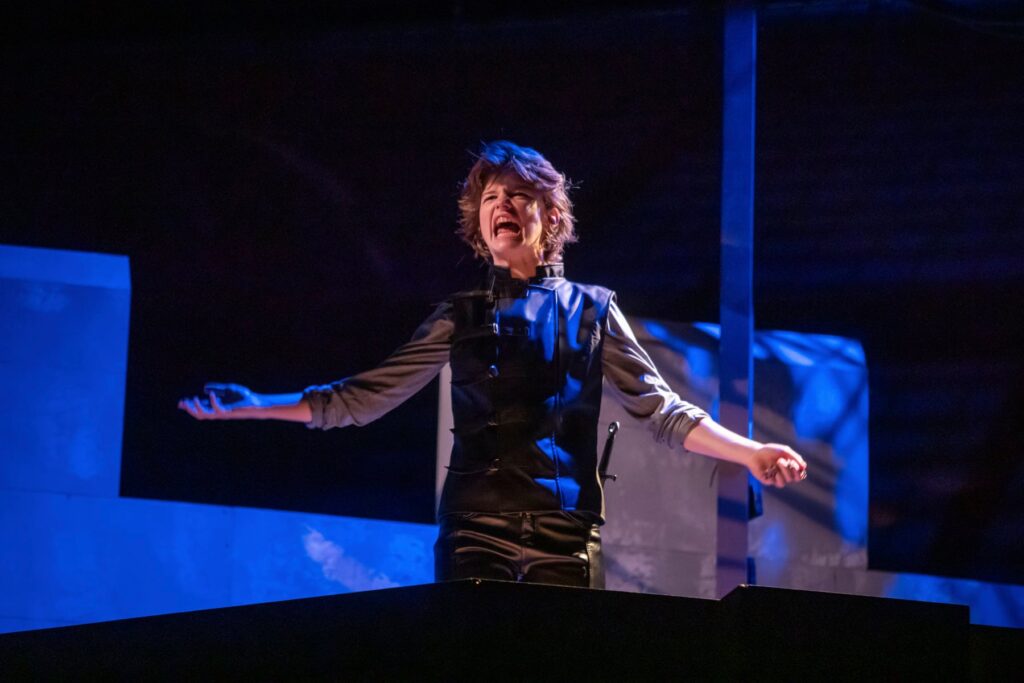

To be sure, Hamlet is no teenager but a young man of about 30. That being said, he can come across as a precocious adolescent, and this was reenforced by Dakota Collins’s superb performance. Through him, Hamlet was androgynous, super sensitive, and somewhat innocent. As a result, I understood much better why he would be so affected by the machinations of those running society and could imagine those Montana school children being similarly affected. As the Post article observes,

No one knows exactly what led the teenagers to end their lives. But people here are thinking: What if the adults in the Flathead, with all their anger, have provided a terrible example for the children?

“We’re such a highly wounded community right now,” said Kyle Waterman, a gay city councilman who received training this year in making a citizen’s arrest in case he feels physically threatened. “It’s been hard to show people we’re here for our kids.”

Now put yourself in Hamlet’s situation. Thinking his father has everything in hand, despite a war with Norway, Hamlet feels free to go away to college. When he returns, however, everything has been turned upside down, with his uncle suddenly his king and stepfather. Claudius and Gertrude want him to shrug off his father’s death and adapt to the new reality but, even before he learns of the “murder most foul,” he wants to erase himself from reality. He even contemplates self-slaughter as everything seems “weary, stale, flat and unprofitable”:

O, that this too too solid flesh would melt

Thaw and resolve itself into a dew!

Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d

His canon ‘gainst self-slaughter! O God! God!

How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable,

Seem to me all the uses of this world!

Fie on’t! ah fie! ’tis an unweeded garden,

That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature

Possess it merely.

Things, of course, go from bad to worse once Hamlet Sr.’s ghost reports the murder. Already fragile, Hamlet is pushed over the edge. Whatever idealism he had has been shattered, as we see in his discourse with his former friends Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern:

I have of late—but wherefore I know not—lost all my mirth, forgone all custom of exercises; and indeed it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame, the earth, seems to me a sterile promontory, this most excellent canopy, the air, look you, this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire, why, it appears no other thing to me than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours. What a piece of work is a man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculty! in form and moving how express and admirable! in action how like an angel! in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the world! the paragon of animals! And yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? man delights not me…

As Hamlet figures out that his friends have been set up to spy on him, and as he detects Polonius setting up Ophelia to spy on him as well, he feels less and less able to trust anyone or anything. His mother’s behavior has prompted him to wonder about Ophelia (“frailty, thy name is woman”), and the visiting actors’ ability to feign tears over imaginary characters (“What’s Hecuba to him or he to Hecuba?”) only furthers his sense of unreality.

Sensing himself half mad, Hamlet once again thinks upon death in his most well-known soliloquy:

To be, or not to be, that is the question,

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep;

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to, ’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish’d.

Given his active imagination, however, even death doesn’t seem a simple solution. His reasoning, fortunately, has the virtue of forestalling a suicide:

To die, to sleep;

To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there’s the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause: there’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life;

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscover’d country from whose bourn

No traveler returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Faced with conflicting pressures, Hamlet becomes increasingly erratic and high-strung. Like a teenager, he vacillates between crippling self-doubt and precipitous action. Late in the play he reflects upon death once again as he muses upon the skull of a man who played with him as a child. Only at the end of the tragedy does everything become clear to him.

Did those Montana teenagers have a version of Hamlet’s confusion? Did reality to them seem unstable because of the way that adults were behaving? Between Trump unleashing America’s id and a world-wide pandemic affecting every aspect of life, there’s plenty to point to. When the instability of adolescence comes up against adults who are unwilling or unable to provide the necessary support systems–when grown-ups act like teenagers, in other words–tragedy seems inevitable.