While it made sense that my student Mary would be drawn to Northanger Abbey (see my Thursday and Friday posts), Mansfield Park was the Jane Austen novel that brought out her best. She identified with the heroine Fanny Price for very understandable reasons. With her speech impairment, Mary, like Fanny, grew up feeling marginalized as all the “beautiful” people around her sucked up the attention. In response, Mary (again like Fanny) developed a rich interior life that others were unaware of.

There is one area in particular where Mary’s life and the book match up.Mary’s mother had to fight when school authorities wanted to put Mary in special education classes. Meanwhile Maria and Julia Bertram, Fanny Price’s cousins, see Fanny as deficient for not knowing a number of rote facts that they had been taught by their governess: the Roman emperors, figures from mythology, and “all the Metals, Semi-Metals, Planets, and distinguished philosophers.”

Was Mary’s public school guilty of the condescension that guides the judgment of the Bertram sisters? Here is how Maria and Julia’s dreadful aunt Norris answers their questions about their “deficient” cousin: “[Y]ou are blessed with wonderful memories, and your poor cousin has probably none at all. There is a vast deal of difference in memories, as well as in every thing else, and therefore you must make allowance for your cousin, and pity her deficiency.”

For Mrs. Norris, education is a means of keeping people in their proper places and maintaining the status quo. “[I]t is not at all necessary,” she says, “that she should be as accomplished as you are; –on the contrary, it is must more desirable that there should be a difference.”

Austen’s views on the results of the girls’ education is scathing: “[I]t is not very wonderful that with all their promising talents and early information, [Maria and Julia] should be entirely deficient in the less common acquirements of self-knowledge, generosity, and humility. In everything but disposition, they were admirably taught.”

I love the angry understatement in that last sentence. Few writers can deliver a subtle knock-out blow as well as Jane Austen.

Since Mary’s senior project was about images of reading in Jane Austen, how did Mansfield Park fit into her thesis? The novel has two significant reading dramas. The first seems small but Mary lasered in upon it. Fanny Price does have one sympathetic cousin, Edmund, who pays attention to her and becomes her reading coach:

Kept back as she was by everybody else, his single support could not bring her forward; but his attentions were otherwise of the highest importance in assisting the improvement of her mind, and extending its pleasures. He knew her to be clever, to have a quick apprehension as well as good sense, and a fondness for reading, which, properly directed, must be an education in itself. Miss Lee taught her French, and heard her read the daily portion of history; but he recommended the books which charmed her leisure hours, he encouraged her taste, and corrected her judgment: he made reading useful by talking to her of what she read, and heightened its attraction by judicious praise. In return for such services she loved him better than anybody in the world except William [her brother]: her heart was divided between the two.

The other reading drama, however, sets Edmund and Fanny at odds. The Bertrams have become friends with free spirits Henry and Mary Crawford, and together they decide to put on a home theatrical, the German play Lovers’ Vows. The subject matter of play was sensational for the time, involving a son born out of wedlock that comes back to save his starving mother. He clashes with his upper-class father who, in the end, marries mom. The play offers the Bertrams and Crawfords the chance to flirt with each other under the cover of their characters. Fanny and at first Edmund see the production as immoral.

But Edmund is won over after being pressured by the others, especially when he realizes that he will be able to play out tender love scenes with Mary Crawford, whom he is falling in love with. In the end it is only Fanny, already marginalized, who must speak up for the morally right thing to do, and she is overridden. Only when an appalled Sir Thomas discovers the production are Fanny’s objections validated.

It took a long time for Mary and me to understand why she found this episode significant. It was related to her anxieties about graduating. But we didn’t discover this until two weeks before the project was due.

Here’s how the two are connected. In the episode, Fanny must challenge the man who has been her trusted mentor. Having been trained by Edmund to be a moral and discriminating reader, she realizes that the Crawfords and Bertrams are turning Lovers’ Vows into a vehicle for (by the standards of the time) self-indulgent sensuality. Yet she then watches Edmund sign on anyway.

The episode signaled to Mary that she couldn’t rely on mentors to know everything and to pave the way for her. Sometimes mentors are unreliable. As she was only a few weeks from leaving the safe haven of St. Mary’s and of separating from parents and teachers, voicing this realization out loud was hard. I’m not saying that her mother or teachers were letting her down like Edmund. But she did have to break with them/us. At a time when she was feeling as alone and battered as Fanny, she had to learn to be strong.

Fanny provided a heroic model. Once again drawing on her reading and Edmund’s tutelage, Fanny is able to resist the intense pressure, from Sir Thomas on down (including Edmund), that she betray her heart and her morals and marry the rakish and selfish Henry Crawford. In their eyes, it would be a splendid marriage, but she holds fast. No heroine in Jane Austen’s fiction, I think, goes through such a daunting struggle as her quietest heroine.

As I noted, Mary didn’t realize that her project was about mentors as well as about books until a few days before the project was due. I thought she was all settled on a theme about the effectiveness (and ineffectiveness) of books in preparing one for life, but she wouldn’t let her discussion of mentor figures go, even though it was “messing up” a clear line of thought. When I finally saw how all her pieces fit together, I wrote her a long note apologizing for having not seen their importance. I told her that she already had an A for the project, whatever she chose to do further If she wanted to revise, however, she should link books and the mentors who teach us how to read them.

Moments like this keep one humble as a teacher. We do our best to listen to students and help them develop their ideas in the directions they want to go. But we can miss things and give poor advice. Teaching, as the saying goes, is an art, not a science.

Mary rewrote her entire project in three days. She knew that she was writing for her life and needed to make it as accurate as possible. In the end she concluded that Austen’s heroines must ultimately move beyond the books and mentors that they have come to rely on. Because a good senior project is always a coded autobiography, I knew Mary was speaking for herself as well as for Austen. The final product was magnificent. I cheered.

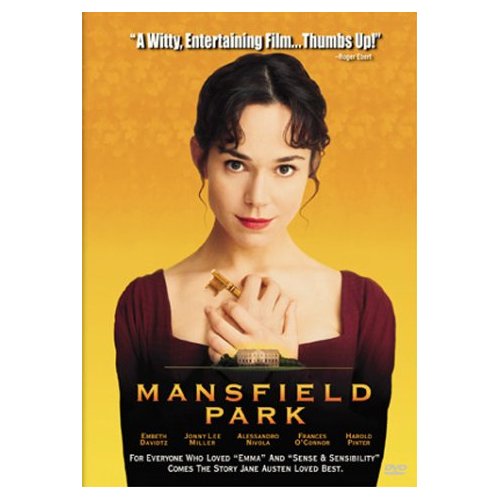

Addendum: I have mixed feelings about the visual I use today, a poster from Patricia Rozema’s Mansfield Park. Rozema radically alters the character of Fanny, turning her more into a cross between an Elizabeth Bennett and an idealized Jane Austen. This is undoubtedly because it’s hard to excite modern audiences with a quiet and reserved heroine. The result is a film that fails to plumb the depths of Fanny’s real heroism and that creates an inconsistent heroine. Why would this witty and outgoing woman (as Rozema depicts her) suddenly become prudish at the film’s end?