Jason Blake, who teaches English at the University of Ljubljana, submitted a counterargument to my case against forbidding use of the first-person singular in literature essays. While I think there are other ways than an outright ban to deal with the problems that he identifies, I like his point that one can write a committed essay without using “I” and an evasive essay using the pronoun. And I love his Frederick Exley quote.

By Jason Blake, English Dept., Univ. of Ljubljana

My excellent and quirky high school English teachers had some great rants, many directed at students who used the first-person singular in essays. But even those witty hippy rants, even Mr. Mitchell with his legendary “People are so fucking prejudiced…” diatribe, paled against this one from Frederick Exley’s A Fan’s Notes:

A freshman had nuns cloistered in a “Beanery,” a sophomore thought the characters in Julius Caesar talked “pretty damn uppity for a bunch of Wops,” […] and a senior considered “Hamlet a fag if I ever saw one. I mean, yak, yak, yak, instead of sticking that Claude in the gizzard, that Claude who’s doing all those smelly things to his Mom.”

Exley is unfazed by the slurs and sympathetically bemused by the “touching bewilderment of these students” as they grapple with the Bard. What really irks him is

an English department chairman who clung to such syntactical myths as that either different from or different than are permissible as the former is used in America and the latter in England. Though I had done some substitute work, this was my first contractual obligation, I was bringing to it a typically asinine and enthusiastic aplomb, and at this point I sought the floor [during a staff meeting]. “I’ve heard this for years,” I said, “have always looked for it, and have found that most English writers use different from. Without a Fowler handy I haven’t the foggiest how this argument got started, but I suspect that some prose writer of Dean Swiftian eminence got smashed one day, inadvertently substituted than for from, and for the past two hundred years the dons at Oxford and Cambridge have been scratching their heads and picking their noses over it. But this professorial bickering has nothing to do with us. Between getting smashed and cracking up their hot rods, initiating each other into their sex clubs, and having their rumbles, these little dears are looking to us for direction” – loud laugh here from the back of the room, issuing from a Dartmouth man who taught English and Latin – “and we ought to give it to them. Oughtn’t we to take a hard and arbitrary line and say it’s different from, period?”

If Exley’s narrator (also named Frederick Exley in this “fictional memoir”) can get so angry about “different from” versus “different than,” what might he have said about the use of “I” in high school essays? He might have settled the question for good by imposing a “hard and arbitrary line” for students to follow. After all, for developing minds wrestling with the essay form, there is comfort in firm rules.

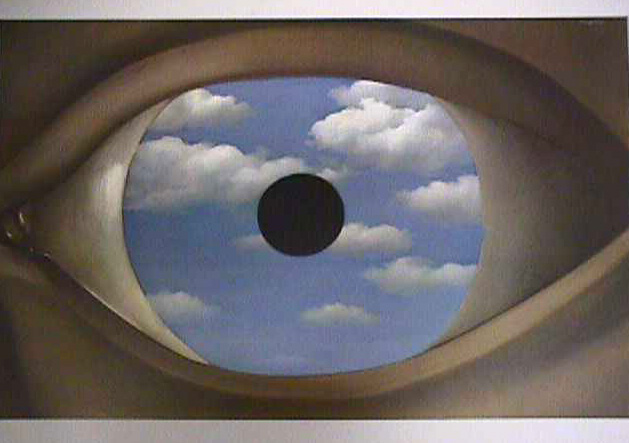

Comfort rules aside, the no-“I” edict seems especially arbitrary. Robin’s recent post “How Teachers Can Make Lit Real” pointed out the absurdities of banning the first-person singular. My own English teachers at least took the time – in between sharing their lists of 100-favorite books, occasionally taking cheap-shots at “lesser disciplines” like mathematics and physics, and describing their battles with uptight parents (something about an “inappropriate” Salvador Dalí film) – to say why “I” was out. They provided the usual justifications: sentence clutter, fluffy subjectivism, and the tummy-ache problem of refuting a thesis like “I think Hamlet was Italian.” The teacher can prove that Hamlet was not Italian, but he can’t prove whether you think Hamlet was Italian, just as he can’t prove whether you have a real tummy ache on a glorious Friday afternoon when your boyfriend happens to be waiting for you in the parking lot. Such arguments against “I” are surely generic and universal, and no doubt anyone reading this blog has heard them before.

Here at the University of Ljubljana, I’m tempted to ban “I” for another reason, one that is perhaps culturally specific: students use it to run away from the text. They use “autobiography” as a not-so-slick avoidance strategy within the actual essay. Do American students also write so frequently about the self instead of the self and literature?

Here’s exactly what I mean by “essayistic autobiography.” (The nickname and samples are adapted from my Writing Short Literature Essays: A Textbook with Exercises for Slovenian Students.):

When I first sat down to write this mini-essay for our first-year poetry class, I realized almost immediately that it would not be an easy task because I have never written a poetry essay before – back in high school, I never had to write a poetry essay because our literature classes were all about names and dates and memorizing…

That’s not much of a hook in a classroom where almost every student is writing his/her first poetry essay in English. Though “I” is repeated four times in the sentence, the reader learns little about the individual doing the writing, even less about how she reads a poem. In the most extreme instances, such filibustering can go on for a hundred words, about two-thirds of a typical Slovenian sentence and half the length of the first mini-assignment. It is clear that the student is dodging the assignment, perhaps out of fear that a truly personal response might be punished. If you like numbers, when I forget to address this problem ahead of time, approximately one-third of a first-year class will write that sort of essay.

I understand why. It must be terrifying to be asked to bare your soul in the neat form of an argument. This example of “autobiography,” however, is more troubling and just as common:

I had a tough time understanding this difficult poem; I had to look up a number of words in the dictionary, and I could not even find all of the unknown words.

The sentence is deeply disturbing because of the self-blame it oozes. “I had a tough time” and “I could not even find…” suggest that the student feels there’s something morally or intellectually wrong with her because she doesn’t immediately grasp all the insults and allusions in, say, Shelley’s “England in 1819” (quoted in full below).

Feeling “stupid” because you don’t “get” a poem kills literary enjoyment, and sometimes removing the “I” can help the student overcome an engagement-hurdle. That said, I can provide useful feedback for the above sentence, which is a promising first step because the student – though she may not realize it – has pinpointed her difficulties in engaging with the poem. It’s the words, stupid… and, by the way, you are not stupid!

If a student points out that she “had to look up a number of words,” she can soon reflect on the voice or tone of the poem. Is the speaker noxiously wordy? If so, how does he sound? Scholarly? Inauthentic? Why don’t the words appear in the Oxford Advanced Learners’ Dictionary? Are they archaic, as in Coleridge’s “Now wherefore stopp’st thou me?” from “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner?” Slang, as in “Papa’s gonna buy you a mockingbird?” Vulgar, as in Philip Larkin’s “This Be the Verse?” (The last is an invented example. Turns out, the f-word is in the Oxford Advanced Learners’ Dictionary, and I’m pretty sure all of my Slovenian students have heard that word before.)

From the initial and tepid “I had to look up a number of words in the dictionary,” it’s not hard to arrive at “I had to look up a number of the archaic slanderous words in the dictionary,” and an even shorter step to “there are many archaic and slanderous words in this poem.” Then the student can start thinking about the poem and examining her reacts to slander.

My hopes when discouraging the first-person pronoun is, paradoxically, to promote engagement with literature. The self will always be there in a literature essay. My aim is to help students trim their essays of what went on before they started writing the essay, and because Slovenians excel at guilt, to direct them to the work rather than revel in self-flagellating “I don’t get it.”

Again, it is a special form of arrogance to assume that your classrooms are mysteriously different from those of colleagues in other countries – two years ago I taught a course on sports literature in Maine and realized that my “Slovenian” essay problems were not unique to Central Europe. Perhaps I am mistaken in seeing “I” as a common means of avoiding the self in literature essays.

As a conclusion, here’s a wonderful and personal first sentence to a short essay on Shelley’s anti-monarchy rant: “We all occasionally criticise the way our country is run, but ‘England in 1819’ by Percy Bysshe Shelley is absolutely dripping with contempt.” There’s no lack of voice, there’s wonderful engagement with the poem, and, more wonderful still, the student tied the 200-year-old poem to the present. Isn’t this much fresher than “When I sat down to read ‘England in 1919,’ it hit me as a difficult poem because…”?

Here’s Shelley’s poem, which reads a bit like an Exley rant:

England in 1819

An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying king,–

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn,–mud from a muddy spring,–

Rulers who neither see, nor feel, nor know,

But leech-like to their fainting country cling,

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow,–

A people starved and stabbed in the untilled field,–

An army, which liberticide and prey

Makes as a two-edged sword to all who wield,–

Golden and sanguine laws which tempt and slay;

Religion Christless, Godless–a book sealed;

A Senate,–Time’s worst statute unrepealed,–

Are graves, from which a glorious Phantom may

Burst, to illumine our tempestous day.