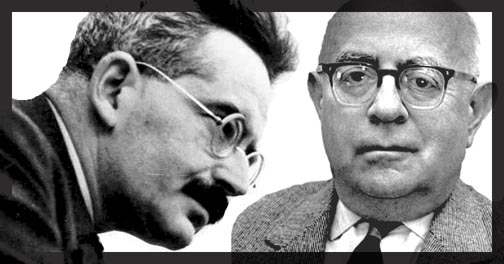

An excellent Alex Ross article in the most recent New Yorker argues that we should bring back the Frankfurt School, most notably Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno. I feel fortunate to have been immersed in these thinkers as a history major at Carleton College (1969-73) and appreciate the case that Ross makes.

The Frankfurt School was a collection of neo-Marxist social theorists at Goethe Institute in Frankfurt, Germany in the 1920’s and 1930’s, a number of whom fled to the United States with the rise of Hitler. People started rereading them in the 1960s when they/we were looking for ways to understand the dynamics of advanced capitalist society. I remember feeling at the time that our very ability to imagine alternatives to the society we were living in was threatened by capitalism’s ability to subsume everything.

In the 1990’s, with the triumph of Reaganism, Marx no longer seemed relevant to the modern world. Ross points out, however, that this has been changing with recent developments:

With the fall of the Soviet Union, free-market capitalism had triumphed, and no one seemed badly hurt. In light of recent events, however, it may be time to unpack those texts again. Economic and environmental crisis, terrorism and counterterrorism, deepening inequality, unchecked tech and media monopolies, a withering away of intellectual institutions, an ostensibly liberating Internet culture in which we are constantly checking to see if we are being watched: none of this would have surprised the prophets of Frankfurt, who, upon reaching America, failed to experience the sensation of entering Paradise. Watching newsreels of the Second World War, Adorno wrote, “Men are reduced to walk-on parts in a monster documentary film which has no spectators, since the least of them has his bit to do on the screen.” He would not revise his remarks now.

Ross focuses on Benjamin and Adorno because of the important ways they pushed each other on the subject of popular culture. Benjamin trumpeted how popular culture seemed a vibrant way of liberating us from traditional class society. His most famous quotation may be “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism,” and he looked to popular culture as a way of working outside the parameters of traditional power centers. Adorno, by contrast, argued for the continuing importance of the traditional arts.

Each of the men had his blindnesses, but Ross says that the debate between the two is vital. Adorno overlooked the importance of certain popular forms, especially jazz, while Benjamin could be guilty of failing to see how mass culture could itself be taken over by capitalism. At one point Adorno noted that both high and low culture were in danger of being ensnared by commerce:

Both bear the stigmata of capitalism, both contain elements of change. . . . Both are torn halves of an integral freedom to which, however, they do not add up. It would be romantic to sacrifice one for the other.

Ross observes,

In particular, it would be a mistake to romanticize the new mass forms, as Benjamin seems to do in his mesmerizing essay [“Art in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction”]. Adorno makes the opposite mistake of romanticizing bourgeois tradition by denying humanity to the alternative. The two thinkers are themselves torn halves of a missing picture. One collateral misfortune of Benjamin’s early death is that it ended one of the richest intellectual conversations of the twentieth century.

Ross points out that Fredric Jameson, a contemporary Marxist, attempts to reconcile the two thinkers, writing that the

“cultural evolution of late capitalism” can be understood “dialectically, as catastrophe and progress all together.”

I appreciate Ross’s conclusion where he talks about the increasing difficulty to find freedom within art as capitalism seeks to intrude at all points. It can turn classical music into elevator music and advertising jingles, and it can commercialize hip-hop. Ross ends his article by talking of the challenges of finding liberation through art:

Above all, these figures present a model for thinking differently, and not in the glib sense touted by Steve Jobs. As the homogenization of culture proceeds apace, as the technology of surveillance hovers at the borders of our brains, such spaces are becoming rarer and more confined. I am haunted by a sentence from Virginia Woolf’s The Waves: “One cannot live outside the machine for more perhaps than half an hour.”

Art’s major mission is to help us step outside the machine, even if only momentarily.