Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at [email protected]. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Wednesday

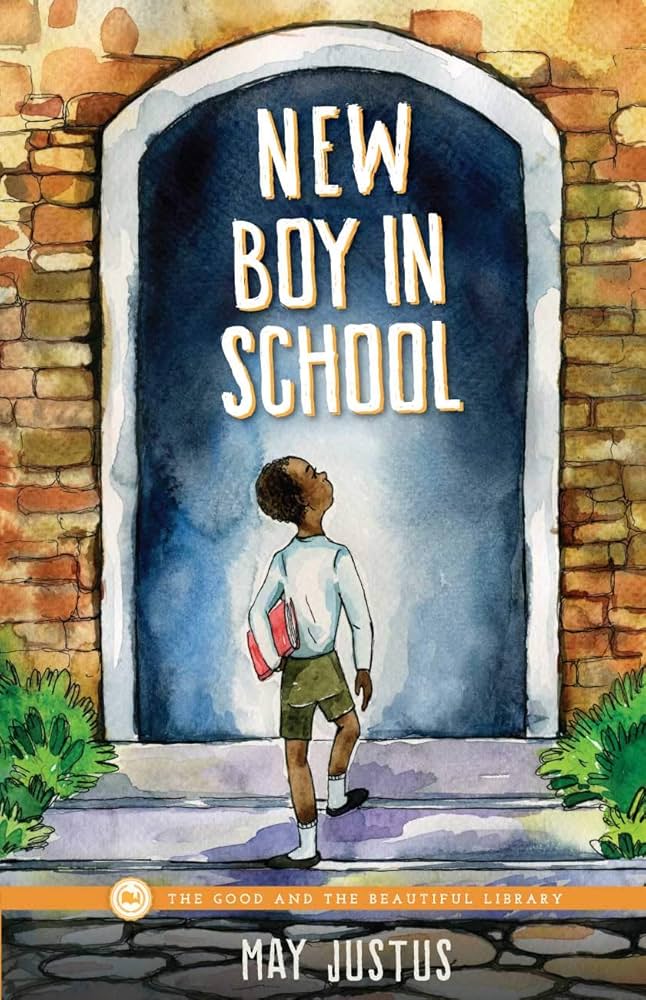

As I comb through childhood memories for a talk I’m giving tomorrow, I’ve just reread, for the first time in 60 years, a civil rights children’s book that was dedicated to me and my brothers. New Boy in School (you can read it here) is about an African American boy who, attending a newly integrated school, discovers he is the only student of color in his class. The book is so close to the experience of the one Black kid in my own seventh grade class that I can’t help but wonder if author May Justus borrowed some of it from me. Maybe I shared my encounter with Ronnie Staten with her, or at least with my parents.

There’s no way I’ll ever know and it doesn’t really matter but it’s fun to think about. Here’s the story:

As I’ve reported in the past, I grew up in the Appalachian south—in Sewanee, Tennessee—and as a child I was one of the child plaintiffs in a landmark civil rights case. In 1961 four White families and four Black sued the Franklin County Board of Education on behalf of their children for failure to integrate. Citing the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, we won the case and integration took place in two stages. In the first year only a few of Sewanee’s Black children entered Sewanee Public School while full integration happened the following year. Ronnie was the one Black placed in my seventh-grade class.

On his first day, I made a special point of reaching out to him on the playground. While he appeared to appreciate it, he was more interested in joining the other boys playing basketball. I realized at the time that it was probably the best thing he could do to speed acceptance but was glad I made the effort.

Closely watching the progress of Sewanee’s integration was Miss Justus (as we called her), who lived 10 miles away. An accomplished author, Miss Justus had come to the area with fellow teacher Vera McCampbell in 1931 as part of a John Dewey-inspired educational experiment. Dewey’s philosophy is that practical and abstract education should go hand in hand so that, for instance, one learns arithmetic from buying groceries and reading from undertaking various life tasks. Miss Justus initially set up a one-room school where the kids cut firewood and cooked their own lunches, and later in life she wrote a Little Golden Book about the approach (The Wonderful School of Miss Tillie O’Toole).

Not long after Miss Justus and Miss McCampbell set up their school, Myles Horton established the legendary Highlander Folk School nearby. Originally established to support Appalachian coal miners, Highlander moved into civil rights activism in the 1950s. As the only integrated conference center in the south, Highlander became a hub of the civil rights movement with activists from all over the south gathering to discuss and share strategies and approaches. Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, Jesse Jackson, and others attended the workshops, and Miss Justus, who appreciated what Highlander was doing, volunteered herself to be the organization’s secretary and treasurer.

Although the state of Tennessee eventually chased Highlander out of Grundy County, Miss Justus stayed. Looking back I’m surprised that she didn’t experience more flack for her Highlander association. Maybe she was too famous and too beloved. Her friend Vera, however—now teaching in the public school system—was fired a year before she was due to collect her pension in a particularly vindictive move.

In any event, the suit against Franklin County had been partly the brainchild of Septima Clark, an extraordinary African American woman who was Highlander’s education coordinator, so that she, Miss Justus, and the Sewanee families were all in regular contact. Out of these associations came New Boy in School.

Unusual for 1963, the book has a Black protagonist, Lennie, whose family has just moved into the area. Terribly unhappy, Lennie hides from the other students but is befriended by Terry, who reaches out. The following day, Lennie brings a ball to class, which evolves into a collective game. Finally, after one final bout of shyness about performing for a school program, Lennie realizes he can contribute a song his father has taught him and all ends well. Maybe Miss Justus saw me as Terry.

I’m wondering if New Boy in School captures at all how Ronnie felt on his first day. (The book probably should have been dedicated to him, but Miss Justus didn’t know the Statens as she knew the Bateses.) While all the Whites are unrealistically nice—the n-word never makes an appearance—the book is good at capturing Lennie’s intense anxiety:

Lennie said nothing. Somehow he was a little afraid in this fine new school. It all seemed so strange to him. Most of the faces about him were friendly–Miss Baker’s and those of the children—but they were white faces.

“There are so many of them,” said Lennie, “and only one of me.” Yes, Lennie was the only Negro boy in the room.

And further on:

When it was time for reading class Lennie paid no attention. He just sat there behind his book. When it was time for recess, and all the children ran outside Lennie stayed in the schoolroom.

Finally Miss Baker took him by the hand, and tried to get him to join in a singing game. As soon as she turned him loose though, Lennie ran off. When the children laughed at him, he hid behind a big bush that grew in a corner of the schoolyard.

As I say, Ronnie was not this shy and I recall an extraordinary moment when a student called him the n-word directly to his face. Ronnie just looked at him and smiled, deflating the student utterly. It’s a moment I will never forget. Years later, I learned that Sarah Staten, Ronnie’s remarkable mother, had coached her kids to do just that.

I am keenly aware, now that I have grandchildren of color, how vital it is to have book protagonists that one can identify with. My grandchildren take it for granted that, of course, book characters will be of multiple races and ethnicities. At the time Miss Justus wrote New Boy in School, however, such books were very few in number. Even Black schools were using the white suburbia Dick, Jane, and Sally books to teach reading.

Of all her books, Miss Justus always said she was proudest of New Boy in School. I myself am proud to have played a role in its creation.

Additional note: Rereading how Lennie wins over his class by his singing, I am reminded of my segregated Boy Scout troop as I was growing up. In one of our summer jamborees—perhaps in 1962—we encountered an all-black troop. My fellow scouts had many unkind things to say about them until we heard them sing, at which point their harmonics put everyone to shame. We had never heard such singing.