Tuesday

Notre Dame in flames is breaking my heart, along with hearts all over the world. For me, Notre Dame is the soul of Paris, and I remember counting the stairs and wandering around the demon statues when I was 11. My attachment was further cemented when I read Victor Hugo’s novel in French at 15. I did not know then, however, that at one time the novel saved the cathedral, which in 1831 was falling apart.

More on that in a moment. First, however, let’s look at Hugo’s celebration of the cathedral. Notre Dame, he observes, is like no other cathedral, being a mixture of different styles:

Notre-Dame is not, moreover, what can be called a complete, definite, classified monument. It is no longer a Romanesque church; nor is it a Gothic church. This edifice is not a type. Notre-Dame de Paris has not, like the Abbey of Tournus, the grave and massive frame, the large and round vault, the glacial bareness, the majestic simplicity of the edifices which have the rounded arch for their progenitor. It is not, like the Cathedral of Bourges, the magnificent, light, multiform, tufted, bristling efflorescent product of the pointed arch.

Drawing on Romantic notions of organic growth, Hugo says the cathedral grew as the nation grew:

Great edifices, like great mountains, are the work of centuries. Art often undergoes a transformation while they are pending, pendent opera interrupta [“the work hangs interrupted]; they proceed quietly in accordance with the transformed art. The new art takes the monument where it finds it, incrusts itself there, assimilates it to itself, develops it according to its fancy, and finishes it if it can. The thing is accomplished without trouble, without effort, without reaction,—following a natural and tranquil law. It is a graft which shoots up, a sap which circulates, a vegetation which starts forth anew. Certainly there is matter here for many large volumes, and often the universal history of humanity in the successive engrafting of many arts at many levels, upon the same monument. The man, the artist, the individual, is effaced in these great masses, which lack the name of their author; human intelligence is there summed up and totalized. Time is the architect, the nation is the builder.

According to Vox’s Constance Grady, in the 19th century Notre Dame

was in a state of horrific disrepair. Its architecture was considered old-fashioned, it was largely neglected, and it was vandalized. Hugo ends the preface of Hunchback with the dark prediction that “the church will, perhaps, itself soon disappear from the face of the earth.”

Thanks to the novel’s success, King Louis Philippe began a restoration project 13 years later. After that, it became Paris’s most popular site.

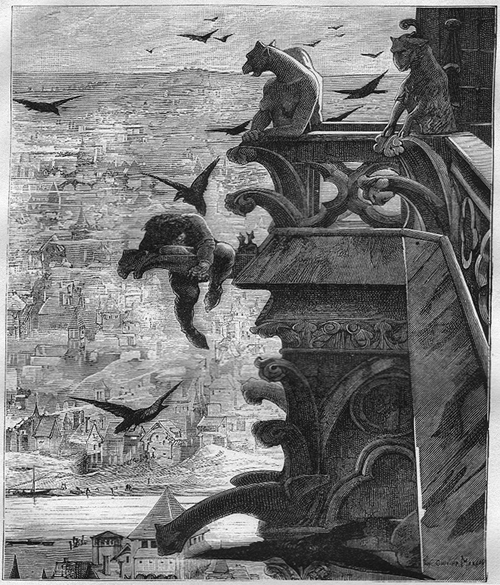

In large part, Hugo’s novel stayed with me because of its tragic ending. I couldn’t believe that the author would allow Esmeralda to be hanged. As I watched images of burning Notre Dame, I recalled my teenage heartbreak. I was Quasimodo once again, gazing upon destroyed beauty, although this time I was gazing at rather than from the towers. In the following scene, the hunchback has just thrown the evil archdeacon who framed Esmeralda over the balustrade, at which point his gaze returns to the gallows:

The deaf man was leaning, with his elbows on the balustrade, at the spot where the archdeacon had been a moment before, and there, never detaching his gaze from the only object which existed for him in the world at that moment, he remained motionless and mute, like a man struck by lightning, and a long stream of tears flowed in silence from that eye which, up to that time, had never shed but one tear.

We are like that man struck by lightning. The tears are flowing.