Thursday

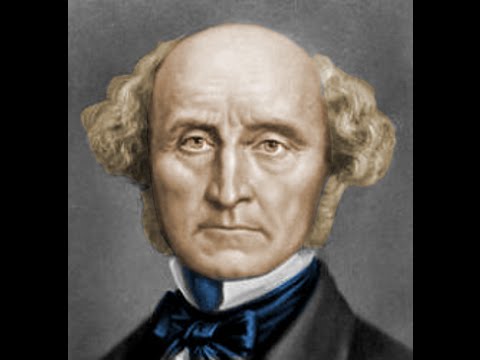

Julia alerted me to an interesting New York Times philosophy column by Adam Etinson that asks the question, “Is a life without struggle worth living.” The column reflects upon the career of utilitarian philospher John Stuart Mill and notes that William Wordsworth’s poetry helped pull him out of a philosophic cul-de-sac, along with an accompanying mental breakdown.

In my mind, the piece should have been entitled, “Is a life without poetry worth living.” Or perhaps, “Poetry makes life worthwhile.”

Mill was a follower of Jeremy Bentham, who believed that “all human action should aim to promote the greatest happiness of the greatest number.” The article observes that Mill

devoted much of his youthful energies to the advancement of this principle: by founding the Utilitarian Society (a fringe group of fewer than 10 members), publishing articles in popular reviews and editing Bentham’s laborious manuscripts.

Utilitarianism, Mill thought, called for various social reforms: improvements in gender relations, working wages, the greater protection of free speech and a substantial broadening of the British electorate (including women’s suffrage).

I remember reading Bentham and Mill in a sophomore ethics class at Carleton College and my soul freezing. I was all for their progressive agenda, but the algebraic way that Bentham went about determining the greatest good seemed to deprive life of color. I’ve been teaching Shelley’s Defence of Poetry this week, and he pretty much says the same thing about utilitarianism.

Mill’s mental breakdown therefore does not surprise me. Mill explains that his depression stemmed from his fear that, if a perfect society were ever achieved, he wouldn’t experience great happiness and joy. In other words, he sensed that his life-long goal wouldn’t result in the end that he wanted. We might say that he needn’t have worried—odds are we will never achieve a perfect society—but his doubts about his project plunged him into despair.

Mill says that he was saved by Wordsworth’s poetry:

What made Wordsworth’s poems a medicine for my state of mind, was that they expressed, not mere outward beauty, but states of feeling, and of thought coloured by feeling, under the excitement of beauty. They seemed to be the very culture of the feelings, which I was in quest of. In them I seemed to draw from a source of inward joy, of sympathetic and imaginative pleasure, which could be shared in by all human beings; which had no connexion with struggle or imperfection, but would be made richer by every improvement in the physical or social condition of mankind. From them I seemed to learn what would be the perennial sources of happiness, when all the greater evils of life shall have been removed… I needed to be made to feel that there was real, permanent happiness in tranquil contemplation. Wordsworth taught me this…

In other words, it is not only material conditions that give our life joy and meaning. To be sure, it is important that we work to improve our physical and social conditions, but that’s not all there is to life. I imagine Mill being moved by such passages as this one from Tintern Abbey:

And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

In Defence of Poetry, Shelley puts his finger on Mill’s malaise, saying that utilitarians are mere reasoners or mechanics, confining themselves to our animal and social needs. While they have an important role to play, they miss an important dimension of what it means to be human. For this, we must turn to poetry:

Poetry is indeed something divine. It is at once the centre and circumference of knowledge; it is that which comprehends all science, and that to which all science must be referred. It is at the same time the root and blossom of all other systems of thought; it is that from which all spring, and that which adorns all; and that which, if blighted, denies the fruit and the seed, and withholds from the barren world the nourishment and the succession of the scions of the tree of life. It is the perfect and consummate surface and bloom of all things; it is as the odor and the color of the rose to the texture of the elements which compose it, as the form and splendor of unfaded beauty to the secrets of anatomy and corruption.

William Blake makes a similar point when he attacks what he sees as the secular and sterile Enlightenment:

Mock on, Mock on, Voltaire, Rousseau;

Mock on, Mock on, ’tis all in vain.

You throw the sand against the wind,

And the wind blows it back again.

And every sand becomes a Gem

Reflected in the beams divine;

Blown back, they blind the mocking Eye,

But still in Israel’s paths they shine.

The Atoms of Democritus

And Newton’s Particles of light

Are sands upon the Red sea shore

Where Israel’s tents do shine so bright.

Blake wasn’t against science and he certainly wasn’t against the social causes to which Mill devoted his life. We miss out on something essential, however, when we break reality down into component parts (the atoms of Democritus) and see the universe as an intricate machine, even a machine chugging towards justice and equality for all. No wonder a philosopher thinking that way would descend into depression.

Mill’s flattened view of life came about from imagining a world that authors of dystopias have also imagined in works such as Brave New World, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” and The Giver. Missing from such worlds is beauty and higher spiritual purpose.

It appears that Mill found these in Wordsworth and was saved.