Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

If I have been writing a lot recently about Daniel Genis’s Sentence: Ten Years and a Thousand Books in Prison, it is largely because someone who respects great novels as much as I do has special insight into a question I have long wrestled with: can literature carry us through the darkest of times and situations?

It’s an issue I recall encountering in Margaret Drabble’s The Ice Age, which I read 35 years ago, where a character in an Albanian jail finds solace in books and writing. Having had himself exchanged for his partner’s daughter, who has been locked up as a political hostage by the authoritarian regime, Anthony Keating finds prison-with-books as almost a relief from the cutthroat world of business in which he has been engaged. I’ve always wanted to know how realistic this was.

It’s a version of Richard Lovelace’s declaration in “To Alithea, from Prison”:

Stone walls do not a prison make,

Nor iron bars a cage;

Minds innocent and quiet take

That for an hermitage…

In Lovelace’s case, it is thoughts of Alithea rather than books that transform his imprisonment, but still. In any case, Genis shows me a flesh-and-blood person, not a literary character, exploring the issue.

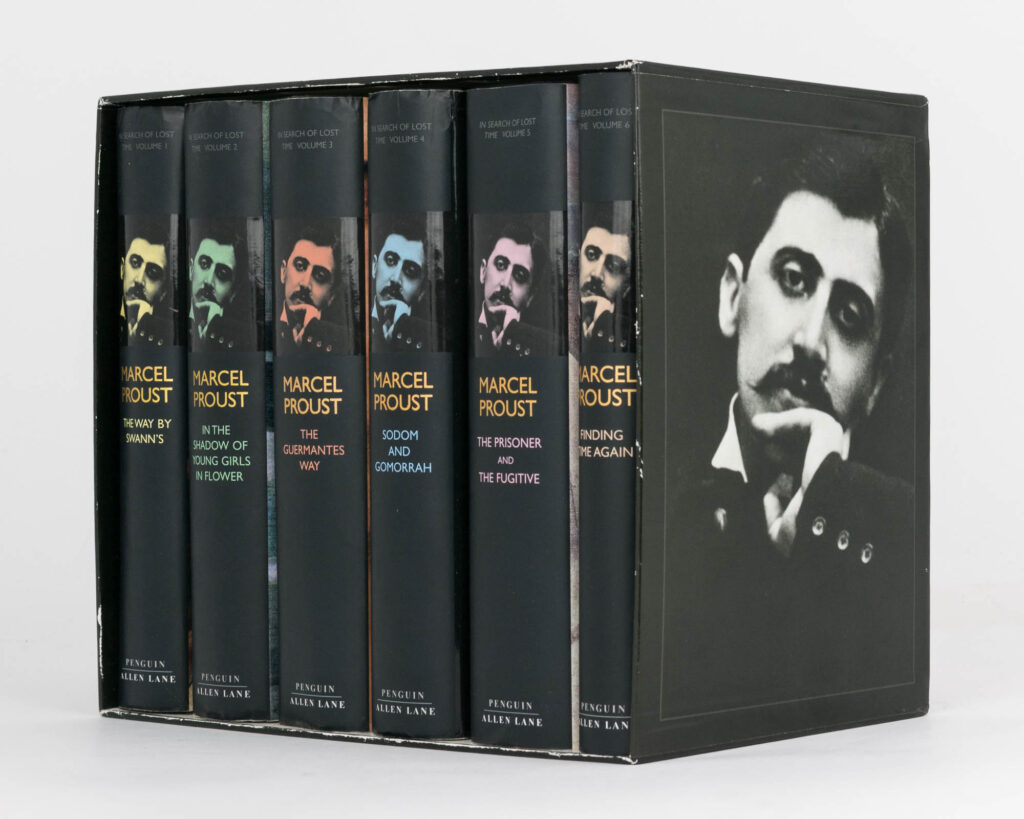

From Genis we see that it’s not enough to have an innocent and quiet mind. In his final bout of solitary confinement, as I noted yesterday, Genis finds himself paired with a schizophrenic roommate who becomes convinced, by the cover art on Robert Musil’s The Man without Qualities, Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, and Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, that Genis is “crazy, satanic, and gay.” Confined with Radar for 23 out of 24 hours, Genis thinks of Sartre’s No Exit, about a coward, a lesbian, and a nymphomaniac yoked together forever in hell:

Sartre wrote No Exit to make a miserable point that I had rejected years earlier as a younger man. As a student at NYU, I could hardly taker seriously his simplistic idea of the French existentialist that “L’enfer, c’est les autres.” [“Hell is other people.”] I loved people, and people loved me. But locked in a room with Radar, ironically almost duplicating the conditions of the play, I realized that what I once thought was facile nihilism was in fact a terrible truth.

Proust, however, provided Genis with a more uplifting vision. To set the background, Genis tells us how he used literature in his search for meaning. As he notes, “After passing the halfway point of my bid [time in prison] and my thirtieth birthday, I ceased reading to learn more about things. I decided that a finer reason to read is to learn meanings. Of life, for example.”

Genis first tried out philosophy before discovering (this has also been my experience) that it is too abstract. Like me, he discovered that he needs plot, characters, setting, imagery and fiction’s other attributes to conduct such a search:

Douglas Adams said that that meaning is forty-two [in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy], which is as good an answer as any. I explored Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and Heidegger, reading the latter on an exercise bike to double my pain. The philosophy of ethics particularly interested me, but the truth was that I was too dense to apply what I learned from these German philosophers to my own situation. Literature was easier for me to digest, so I found myself in The Brothers Karamazov and Crime and Punishment and Knut Hamsun’s Hunger. It was in these great psychological novels of the nineteenth century that I discovered my flawed person. My narcissism and cowardice and compromises were all there, but the solutions—or at least a solution for me—were absent. The redemption I craved, the meaning of my ill-spent life, was not provided by Tolstoy or Dostoyevsky. I did not believe in god or destiny; only I was responsible for my actions, and it wasn’t forgiveness I craved but meaning.

Genis says that for a while he considered Stoicism, as encountered in Tom Wolfe’s A Man in Full. But this too was not enough:

Wolfe led me to reread Epictetus after my first exposure almost twenty years earlier. It helped, especially when I suffered from being treated unjustly. But I was no lifer, and as my remaining time dwindled, I realized I needed a better answer to the question of the meaning of my life. Stoicism understandably gives a man condemned to live out his life behind the wall a way to continue living in the face of hopelessness. But I was soon to be released to go live with my wife in Brooklyn. I needed more than the stiffest upper lip in the world.

In Search of Lost Time provided him with the answers he longed for:

I never argue that Proust has the answer to the eternal question for everyone, but I will eagerly assert that it was Marcel who spent three thousand pages explaining the meaning of my life to me. I found redemption and sanity while I read the longest novel of them all in the box while Radar raged on the cot beneath me.

Genis notes that Proust was “the culmination of a many-years-long effort to read the longest books of world literature.” These books included Joyce’s Ulysses, Wallace’s Infinite Jest, Dostoyevsky’s Brothers Karamazov (which “contains all possible novels within it”), Murakami’s 1Q84, Musil’s The Man without Qualities, and Mann’s four-volume Joseph and His Brothers (which he says enlarged his understanding more than the Torah of what it meant to be a Jew). But Proust “gave meaning to my experience, to my time, my pain, to the whole lot.”

Proust spoke to Genis because of how he handles time, memory, and art. Time first:

Proust describes it as the destroyer of joy in life and sapper of meaning. I simply had years of it to do, though in Proustian terms, we are all “doing” life sentences. The years are obviously the commodity taken away from a prisoner. They stand between him and happiness in the most concrete of ways, but Time is also the opponent of all life. Every passing second erodes whatever joy one has found and carries one closer to the end. The fact that the passage of time inevitably leads to our deaths makes the conduct of our lives mean nothing.

Genis notes that this fact depressed Proust so much that “he retired to a cork-lined room, drank morphine cordials, and masturbated under a sheet when paid rent boys came to perform before him.”

At first, memory appears to offer a solution, especially memories of childhood:

Not by coincidence, the happiness of childhood is the set of memories that torments prisoners as well. Every prisoner is a memory artist, a maestro at remembering. Much of Marcel’s quest for happiness is as a memory master as well, even though the only cage in which he’s locked is the present.

Initially Genis is attracted to how Proust summons up happy memories as a way to be happy:

Perfect recollection of the perfect moment seems to be a supernatural process available to those sensitive enough to do so There are almost psychedelic episodes throughout the narrative that seem to show a flicker in space-time when an instance resonates in synchronicity with a prior one and an ecstatic unity across time and space is achieved.

Because prisoners are generally unable to attain such epiphanies, Genis writes that he read Proust “with an eye toward practical use of his methods.” And in fact, he says that has “had more sex in my head than in bed, and savored fine meals hundreds of times, clutching the memories even as time clawed at them.”

In Proust’s final volume, however, he undercuts the idea that memory is the key to meaning and happiness. As Genis puts it, “No matter how good one is at remembrance, it is a barren occupation. It creates nothing, and mimics time in eating away one’s allotment of years….The essence of life that even the best memory artist can squeeze out is vapid. The only power it has is to pervert and decay. Compulsively remembering revives joy into hysteria, wonder into obsession, and love into jealousy.”

The answer then—at least as far as Genis is concerned—is Art, which alone (as Shakespeare repeatedly tells us in his sonnets) can defeat Time. Genis notes that In Search of Lost Time concludes

with Marcel going off to write the novel that the reader can begin reading anew. Even linearity is thus discarded. The novel ends with the author inviting the reader to return to the beginning. Many do, reading Proust continually throughout their lives.

Genis took away from this that, “to save myself, to make meaning of my life, I had to write.” As he puts it, “My bid was the perfect manifestation of the predations of Time, but there was an answer. Art would redeem the loss. Art alone could save my life.”

Speaking for myself, Art is only one of several ways I find meaning in life, others being relationships, family, nation, world community, religion, and nature. Of course, all these areas are interrelated, but I agree with Genis that literature provides powerful access to them. When Dante, for instance, defines God as “the Love that moves the sun and the other stars,” this is an instance of poetry articulating something that is both beyond us and at the core of our being.

In short, one could do worse than turn to literature to ferret out the meaning of life, the universe and everything.