Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at [email protected]. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Thursday

Over the past year I’ve been reporting on Angus Fletcher’s Wonderworks: The 25 Most Powerful Inventions in the History of Literature, focusing on one literary invention at a time. Fletcher, who is “Professor of Story Science” at Ohio State, takes what could be described as a psychological-anthropological-historical approach to literary techniques, arguing that they have had an impact similar to, say, the introduction of the wheel or the steam engine on human development. Given that my own project is charting how literature changes lives, you can see why I’ve devoted so much attention to the book.

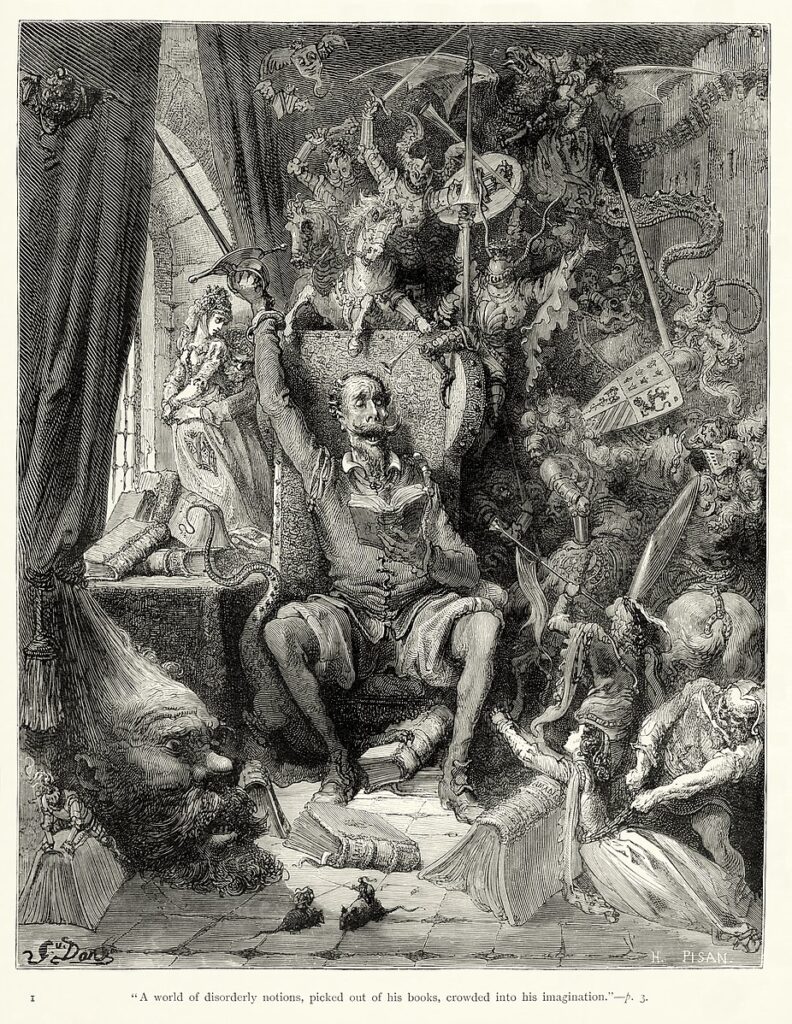

In a chapter that touches on Don Quixote, Greek and Roman comedies (Aristophanes’s Frogs and Lysistrata, Platus’s Pseudolus), and the NBC sitcom 30 Rock, Fletcher looks at works that move between different fictional realities, thereby “prompting our brain to wonder: Is one reality more real? Is one reality more fictional.“

Fletcher’s major example is part 2 of Don Quixote, where the knight encounters people who have read part 1. As Fletcher puts it,

This is a mind bender, not just for the don but for us. A fictional character is riding around the world where his fictions have been published—which is to say, a fictional character is riding around the factual world. So, is the don real? Or is the real world a fiction? Our brain flutters back and forth, inspecting both possibilities, trying to sort out the meta-textual puzzle.

There are yet more twists and turns to come, especially since Cervantes in part 2 is also responding to a counterfeit sequel written by the pseudonymous author Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda. Cervantes’s Quixote calls out this other Quixote as a fraud. Or as Fletcher puts it, “an unreal character sets out to disprove a false fiction by revealing himself in the real world through a genuine fiction.”

Fletcher says the mental gymnastics involved in contrasting fantasy from reality is key to engaging with the world. As we mature, our understanding of what life can contain is enlarged, enabling us to transition from the rules of one environment to the next. While it’s an understanding that Quixote himself has trouble achieving, most of us come to it as we grow older.

But then Fletcher takes another step. Through certain kinds of fiction, we can engage in counterfactual thinking, conducting thought experiments into what an alternate world might look like. Rather than “impossibly reimagining life to suit our fancy,” he writes, we can “learn how to construct plausible dreams that we can export more readily to the life beyond.” We do this with what Fletcher calls “the Comic Wink.”

For a work that employs this wink, he turns to Aristophanes’s comedy Lysistrata, which posits the question, “What would life be like if women ran the government?” The counterfactual thinking encouraged by comedy, he says, “was important to Athenian democracy, which depended for its survival on an openness to new ideas.” But because new ideas can be unsettling, they must be cushioned by a wink, which is “a potent reality-suspending device.” For just a moment, an actor breaks the theater’s fourth wall to assure us, “None of this is really real.” Here’s Plautus’s Pseudolus giving us this wink:

I know, I know. You’re thinking that I’m a two-bit charlatan. But I assure you, all my impossible promises will come true. What kind of a comedy would this be if they didn’t.

You may be familiar with Pseudolus from Mel Brooks’s Something Funny Happened on the Way to the Forum.

While the Comic Wink has proved effective in “getting human brains to open themselves to outside ways of thinking,” Fletcher writes, “it’s only the first half of the dream-come-true technology that modern authors have derived from the Story in the Story.” The second half is the “Reality Shifter.”

Unlike the Comic Wink, which starts in the fantasy but gestures towards the real world, the Reality Shifter “starts in the real world—and then drifts in to fantasy, gently pulling the boundary of reality with it.” This happens in Don Quixote when the hero of part 1 reaches out to readers that the author imagines reading the book, including them as characters in part 2.

And how does this change our lives? Fletcher writes that scientists have shown “that exercises in counterfactual thinking can boost our ability to imagine creative ways to translate fantasy into reality.” It “increases our belief in our ability to change the world; and it improves the problem-solving skills we need to make change a reality. It gives us the will and then gives us a way.”

Put more prosaically, it gets us to think outside the box when we encounter life’s challenges.

In other words, Fletcher gives us yet another reason to make sure our children read imaginative literature throughout their education.