Thursday

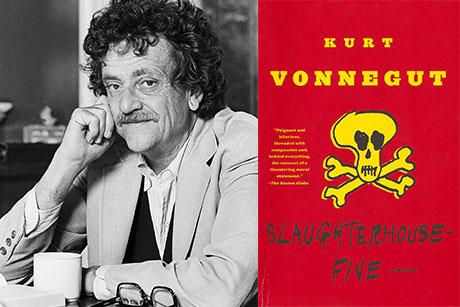

To honor the 50th anniversary of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, I am reposting an essay about how Vonnegut used science fiction to come to terms with the Battle of the Bulge and the Dresden bombing, both of which he experienced first-hand. I owe the ideas to student Chris Hammond, who devoted his senior project to the subject. Chris contends that Vonnegut was only able to approach the trauma through the much-derided genre of pulp science fiction. If baby boomers embraced Slaughterhouse Five, it’s undoubtedly because they were experiencing their own senseless war.

Reposted from May 6, 2014

In today’s post I report on my student Chris Hammond’s essay on Kurt Vonnegut’s use of science fiction to deal with his PTSD, which I first described last November (here). Since then, Chris has become much more specific about the importance of Sirens of Titans, Cat’s Cradle, and Slaughterhouse-Five in the process.

Chris’s central question was why it took Vonnegut 24 years to write directly about the allied firebombing of Dresden, which he witnessed directly as a German prisoner-of-war. (The slaughterhouse where he was imprisoned functioned as a bomb shelter.) In his project, Chris argued that the depth of the trauma was so great that Vonnegut could only articulate it indirectly, through science fiction. Each of his early science fiction novels helped him get closer to telling his Dresden story until he was able to break the silence in Slaughterhouse- Five.

Although Vonnegut was initially an enthusiastic soldier—he enlisted after Pearl Harbor—his capture by the Germans at the Battle of the Bulge brought home to him that he was just a pawn in a larger drama. Then his experience in Dresden caused him to doubt the justice of the allied cause, as did the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima.

He returned to an America that did not want to hear about his war experiences or about Dresden. Like many veterans, he learned that he was supposed to join the general forgetting amidst 1950’s prosperity.

If he could not write directly about the war, however, he could write science fiction, which had entered its golden age. While he appeared to adopt the common tropes of the genre, like space exploration, alien invasion, and time travel, Chris shows how the author subverted each one. In Vonnegut’s fiction, the alien isn’t demonized and technology is a force of malevolent, not benign, control.

Furthermore, Chris shows how each of the science fiction novels is a version of Vonnegut’s war experiences. Each captures (1) Vonnegut’s evolution as a soldier, (2) the silencing he encountered upon returning to the United States, and (3) his longing for a way to handle the psychological effects of Dresden.

In Sirens of Titan (1959), for instance, Vonnegut describes, in heavily coded fashion, how protagonist Malachi Constant follows a trajectory very much like his own: he is uprooted from a life of relative ease, sent into outer space, thrust into a Martian army that controls his mind and sends him on a laughably inept invasion of Earth, returns to Earth to find himself first lionized and then shunned, and is exiled to Titan where he attempts to set up a new life for himself. While on Titan he learns that there has been some master plan in which he has just been a pawn.

In Cat’s Cradle (1963), Vonnegut gets a little closer to directly expressing his own experience since he is now writing about an apocalypse such as he witnessed in Dresden At the behest of the military, naïve scientists have invented Ice 9, which freezes any water it comes into contact with. Unfortunately, some Ice 9 falls into the ocean, thereby ending all life on the planet. To deal with this apocalypse, the protagonist begins practicing a strange religion called Bokononism, which helps him cope even as it acknowledges its own fictionality. Chris notes that Vonnegut’s science fiction worked liked the religion, giving Vonnegut a way of articulating his experiences even though it was obviously fictional.

In Slaughterhouse-Five (1969), Vonnegut is finally able to set a character, Billy Pilgrim, in Dresden as a prisoner of war. Billy’s time travel is a metaphor for Vonnegut’s own PTSD flashbacks. Billy returns to the United States, where he is supposed to live a suburban life, but a brain injury incurred in an accident returns him to Dresden. Then he is abducted by aliens, whose large deterministic vision of the universe provides Billy with a fatalism that both protects him (“So it goes”) and renders his individual life meaningless.

In Slaughterhouse-Five there is also a bad science fiction writer, Kilgore Trout, who functions as Vonnegut’s acknowledgement that science fiction is both necessary and inadequate for expressing the truth of Dresden. In other words, even as Vonnegut writes directly about his war trauma, he acknowledges that this too is an inadequate means of expression, not to mention a clumsy coping mechanism. Fiction isn’t enough but fiction is what he has.

We can’t begin to imagine what it must have been like to experience first-hand a massive human atrocity like Dresden. The amazing thing is that, through the means of a little respected literary genre, Vonnegut was able capture at least some of that hell.

Fiction gets at truths unreachable by straightforward reporting.