Friday

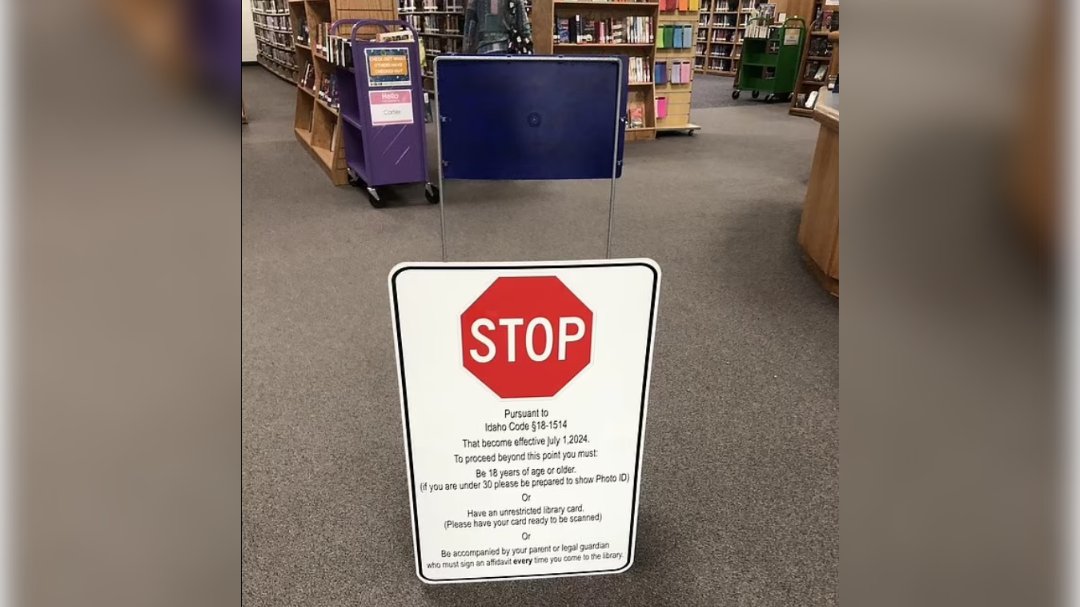

Last month retired Idaho teacher Glenda Funk alerted me to the restrictions that have been imposed on public libraries in that state. Thanks to House Bill 710, passed by the legislature, libraries can now be fined if they don’t respond to patrons objecting to this or that book. As Idaho Education News reports,

The new law establishes a statewide policy for reviewing materials that could be considered “harmful” to minors, including items with sexual content, nudity or homosexuality.

If a patron challenges an item, library officials have 60 days to remove or relocate it, after which the patron can file a lawsuit. A library that violates the law faces a mandatory $250 fine.

The impact varies depending on the size of the library. While, for large libraries, the focus “remains mostly on policy and interpretation,” for small libraries there’s no room to relocate books. In Donnelly Library, for instance, director Sherry Scheline reports that they have had to report all of the library’s materials as “adult” items. As a result, parents must sign waivers for their children to spend time there. The waiver offers three options:

The first option allows parents to waive their HB 710 rights to allow their child to check out materials without a parent present. “I understand the librarians have not been afforded the opportunity to review every item in their inventory, and therefore are not responsible for the content of items that my child may check out,” the waiver reads. “I affirm that my signature on this clause permits my child to circulate materials that may or may not have adult themes.”

A second option allows children to be at the library without a parent present, but requires parental permission for the child to check out materials.

A third option requires children to have a parent with them in the library at all times.

I haven’t read any updates on how the waiver system has worked, but as I was reading the article I was put in mind of an episode in Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, an Italian novel about two smart girls growing up in working class Naples.

Raffaello (Lina) Cerullo is an extraordinary student–she’s the “brilliant friend”–but must abandon formal schooling early in order to work in her family’s shoe repair shop. Narrator Elena Greco is slightly more fortunate in that she can continue on, and she proceeds to take top honors in her classes. But she too is saddened by her limited prospects (her mother wants her to become a secretary, her father wants her to work in city hall) and escapes into the library. And whereas once she and Lina shared everything about what they were learning in school, this has come to an end:

In my spare time I didn’t go out, I sat and read novels I got from the library: Grazi Deledda, Pirandello, Chekhov, Gogol, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky. Sometimes I felt a strong need to go and see Lila at the shop and talk to her about the characters I liked best, sentences I had learned by heart, but then I let it go: she would say something mean; she would start talking about the plans she was making with Rino, shoes, shoe factory, money, and I would slowly feel that the novels I read were pointless and that my life was bleak, along with the future, and what I would become: a fat pimply salesclerk in the stationery store across from the parish church, an old maid employee of the local government, sooner or later cross-eyed and lame.

Elena receives a shock, however, when she receives an invitation to a special event honoring “the most assiduous” library patrons, as determined by the library records:

The small ceremony began. The winners were: first Raffaella Cerullo, second Fernando Cerullo, third Nunzia Cerullo, fourth Rino Cerullo, fifth Elena Greco, that is, me.

Realizing that Lina has been using the library to educate herself, forging the names of her (non-reading) family to get more books, Elena has to suffocate her giggles:

Still feeling that laughter in my eyes, and with an unexpected sense of well-being, after the teacher has asked repeatedly and in vain if anyone from the Cerullo family was in the room, he called me, fifth on the list, to receive my prize. Praising me generously, Ferraro gave me Three Men in a Boat, by Jerome K. Jerome. I thanked him and asked, in a whisper, “May I also take the prizes for the Cerullo family, so I can deliver them?”

Libraries open us to worlds upon worlds, a space of freedom for curious children. Idaho politicians regard this as a threat.