Monday

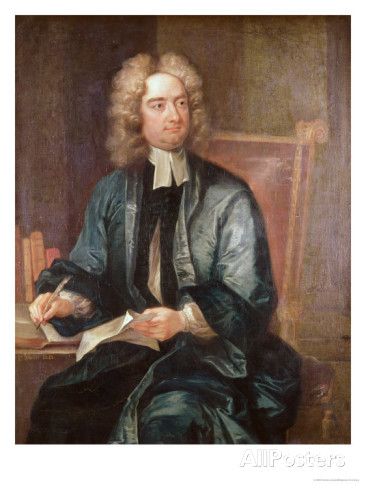

Kudos to Mark Charney of Salon for setting Jonathan Swift loose on Donald Trump. Swift, maybe the greatest satirist of all time, would have had a field day with our politics.

Charney’s excuse for mentioning the 18th century author is a new biography by John Stubbs, which has got to be better than the dull-as-dishwater Irvin Ehrenpreis biography we relied on for years. In an interview with Stubbs, Charney asked him to imagine how Swift would see us:

John Stubbs explains that Swift “wasn’t at all what we’d call a liberal. He had very decided views on what people should believe and how they should behave.” But neither did he suffer fools, as he “detested the abuse of political power, or indeed any excessive use of force by the stronger party.” Swift’s chapter in Gulliver’s Travels in which Gulliver confronts the giant Brobdingnagians shows his rage against, as Stubbs put it in an interview with Salon, “doltish insensibility to those weaker than ourselves.”

Stubbs acknowledges that Swift’s writings are buoyed by an anger that is “very much like the anger against a corrupt establishment that seems to have carried Donald Trump to the White House.” But Stubbs adds that Swift would not let Trump get away with his rhetoric:

Simultaneously Swift incessantly expresses his disgust at how morally outraged and exploited people invariably fall for the cheap promises of politicians.

Charney then tries his own hand at seeing Trump through Swiftian eyes:

The whole Trump campaign sounded like a Jonathan Swift essay. A polite suggestion that Mexican-Americans should vote for someone promising to wall off their country, that Muslims should vote for someone aiming to bar entry of all Muslims to the United States, that lower-income families should vote for someone who plans to strip away any chance they have at healthcare, that women should vote for someone who seems to think that women are lumps of warm flesh to be grabbed at will.

The difference, of course, is that Swift is not serious:

There’s not that much of a gap between “A Modest Proposal” recommending that the poor solve their problems by selling their babies for meat, and the modest proposal that the U.S. keep those “bad hombres” out by building a wall across Mexico that the Mexicans will somehow pay for. The difference is in the intent of the delivery — Trump is serious and his supporters think it’s actually a good idea, whereas Swift writes in such a way that we recognize it as satire, we know that he, the author, does not actually endorse the crazy idea, and readers of his words are likewise in on the joke.

Charney also points out that Swift, unlike Trump, goes after the powerful, not the vulnerable:

[Swift] weighs in on how big fish seem to get away with big illegalities, while the little folk, the ones who can least afford it, are punished. “Laws are like cobwebs,” he wrote, “which may catch small flies, but let wasps and hornets break through.” Although he couldn’t have meant it, his choice of symbolic insect, a WASP, is particularly apt. The hard-luck minorities are always punished, but those white Anglo-Saxon Protestants, as in the Oregon militia fiasco, somehow slip through.

I suspect that the next four years will give me numerous opportunities to refer to Swift, especially to his attacks in Gulliver’s Travels on courtiers using government to line their own pockets. In the meantime, I’ll just mention how Trump’s supposedly magnanimous decision not to prosecute Hillary Clinton reminds me of the Lilliputian king’s “leniency” towards an innocent Gulliver.

In Trump’s case, according to the New York Times, he sees himself as gracious for not taking to court someone who hasn’t done anything indictable (this according to the FBI):

He said he had no interest in pressing for Mrs. Clinton’s prosecution over her use of a private email server or for financial acts committed by the Clinton Foundation. “I don’t want to hurt the Clintons, I really don’t,” he said.

The Lilliputian king, meanwhile, shows “mercy” by not having innocent Gulliver killed for high treason. Instead, he will merely shoot out his eyes. Here’s Gulliver’s response:

[N]or did any thing terrify the people so much as those encomiums on his majesty’s mercy; because it was observed, that the more these praises were enlarged and insisted on, the more inhuman was the punishment, and the sufferer more innocent.

Imagine how such little men (six inches in the case of the Lilliputian) respond when their will is thwarted. And while we’re contemplating Trump’s graciousness, let’s remember that the Justice Department, not the President, indicts people, although that’s not how Trump sees it. We’d all better pray that our Constitution’s Separation of Powers holds.

We’ve never needed more for our own Jonathan Swifts to step up.