Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Tuesday

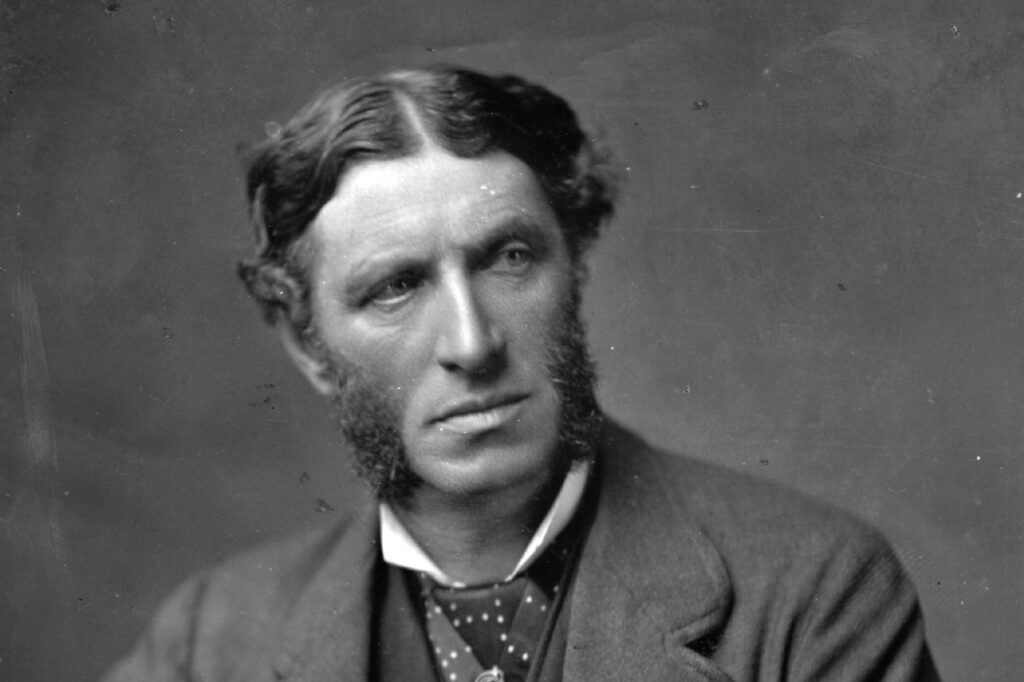

Greg Olear of the Substack blog Prevail has written another wonderful essay on a literary work, this one on Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach,” a poem he ranks among Britain’s ten greatest lyrics. Before I go further, here it is:

The sea is calm tonight.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Ægean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

While he admires the poem, Olear also points out how strange it is. The speaker, rather than using the occasion to focus all his love and attention on his love, instead laments the decline of western civilization. Even the most famous line of the poem doesn’t say what we normally think is says, Olear observes:

For a long time, I read the “let us be true” line as hopeful, where “true” means what it means when it modifies the word “love.” But then I realized I was wrong. He means “true” as in “brutally honest.” What Arnold’s really saying is, “Look, babe, let’s not bullshit each other.” And then: “I know it seems lovely that we are here in this beach house on this moonlit night, listening to the sound of the ocean that’s so relaxing, years from now Sharper Image will make it a standard setting on their noise machines. But I’ve taken the red pill, you see, and I know that’s just an illusion. In reality, the world is a dark, cruel, awful place, and we are all fucked.”

Olear doesn’t mention “Dover Bitch,” the Anthony Hecht parody of the poem, but Hecht makes a related point. Thinking of the scene from the woman’s point of view, he remarks,

To have been brought

All the way down from London, and then be addressed

As a sort of mournful cosmic last resort

Is really tough on a girl…

Olear finds genuine power in the final eight lines, however, regarding them as

all too relevant to the current climate in the United States—a country Arnold much admired, incidentally. We may as well swap “America” for “this world” in the final stanza. Our second largest city and cultural capital is on fire, our media has willfully rejected truth, our so-called leaders have capitulated one by one to the returning despot, and we await the coming of Trump Redux a week from tomorrow.

To which Olear adds, “It’s not just at night when the ignorant armies clash.”

He then, however, manages to find a hopeful message to the poem:

While writing this “Sunday Pages,” I realized that I have misremembered one of the last lines of “Dover Beach.” I thought it was And we are here alone on a darkling plain, where “darkling” is a fancy way of saying “dark and growing darker.” But it’s actually And we are here as on a darkling plain. In Arnold’s darkling view of the world, joy and love and light and certitude and peace and the relief of pain do not…exist. But the one word he never uses is alone. The plain may be darkening, the confusion sweeping, the clashing armies of ignorance and artlessness and stupidity and hatred causing the rest of us to struggle and flee. But it’s we who are here on that plain. We, all of us good guys. We are not alone. And we will be true to one another.

In other words, the main takeaway from the poem is that we don’t have to face this world all by ourselves. Olear concludes,

[I]f we rewind the poem and read it again, keeping all this in mind, we understand that the sea remains calm and the night-air sweet. The eternal note of sadness we let in can also be let out. The tide that withdraws also returns, replenishing the Sea of Faith. And if we stay together, the ignorant armies will expend all their energy attacking one another, and the world really can and will be new and beautiful and various, full of unironic sweetness and light: a land of dreams.

Olear makes one other point which I also make in the chapter I devote to Arnold in my recent book. For all the pessimism expressed in “Dover Beach,” Arnold believed that poetry can save us. As he writes in “Study of Poetry,”

More and more mankind will discover that we have to turn to poetry to interpret life for us, to console us, to sustain us. Without poetry, our science will appear incomplete; and most of what now passes with us for religion and philosophy will be replaced by poetry.

Arnold even had a plan for bringing this about: universal education. Arnold’s day job was a school inspector and he believed that, if teachers taught poetry in the schools, we would experience a new Renaissance. Describing poetry (and cultural generally) as sweetness and light, he writes that

we must have a broad basis, must have sweetness and light for as many as possible. Again and again I have insisted how those are the happy moments of humanity, how those are the marking epochs of a people’s life, how those are the flowering times for literature and art and all the creative power of genius, when there is a national glow of life and thought, when the whole of society is in the fullest measure permeated by thought, sensible to beauty, intelligent and alive. Only it must be real thought and real beauty; real sweetness and real light.

There’s only one point on which I differ from Olear. While he focuses on Arnold’s egalitarianism, emphasizing how culture should be extended to “as many as possible,” the poet also believed in class hierarchy. As Terry Eagleton points out in Literary Theory: An Introduction, Arnold wanted to use culture to maintain the existing class structure, with the middle class ascendent and the working class content with their lot in life. To quote from my book,

Each class will behave properly, he believes, if culture is the basis of the state. The aristocracy will act responsibly, giving up its ancient but now out-of-date privileges, while a cultured middle class will command the moral sway once held by the aristocracy. A cultured populace, finally, will refrain from “rowdy” behavior. In other words, all classes will read poetry, embracing its sensuous images (sweetness) and lofty sentiments (light) to create a more peaceful society.

“Notice who comes out ahead in this formulation,” I go on to say. “The upper class gives up power, the lower class ceases to strive for power, and the middle class takes power. Literature’s role is to make everyone happy with this situation.”

Or as Eagleton memorably sums up Arnold’s view, “If the masses are not thrown a few novels, they may react by throwing up a few barricades.”

But set that objection aside for the moment and think about the impact of every child being introduced to literature. While we may not have achieved Arnold’s Renaissance, I believe that literature requirements have succeeded in opening young minds to new possibilities that they may not have otherwise contemplated. There’s a reason why rightwing authoritarians are attacking English teachers and librarians. Thoughts are blooming in language arts classrooms that are beyond parental control.