Thursday

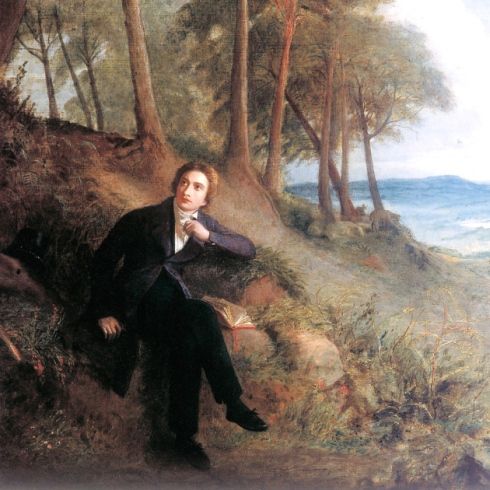

My Sewanee colleague John Gatta, who has been reading my book manuscript, has noted a significant omission: given that Better Living through Literature: A 2500-Year-Old Debate is about the transformative power of literature, why don’t I say anything about imagination? After all, as the Romantic poets saw it, this was the major source of literature’s power.

He’s absolutely right so I’m devoting today’s blog post to some preliminary discussion for an additional chapter. In my chapter on Samuel Johnson, I talk about how, borrowing a metaphor from Hamlet, he discusses how Shakespeare held a faithful mirror up to nature. Romantics scholar M.H. Abrams famously pointed out that the Romantic poets moved from a mirror to a lamp metaphor. In addition to revealing the reality that is there, poets also shine the light of their souls to illuminate the world.

I’m particularly interested in the two connections with the world that, according to poet William Wordsworth, the imagination makes possible: with common people and with nature. In a world in which we feel locked inside our individual selves and alienated from natural world, the imagination reconnects us with something bigger than ourselves.

Elsewhere in the book I talk about how various theorists believe literature can free us from “false consciousness” (Marx and Engels), the prevailing “horizon of expectations” (Hans Robert Jauss), what passes for “common sense” (Antonio Gramsci) or the reigning “world view” (Bertolt Brecht). These are all “soft power” ways (Joseph Nye) that those in authority use to maintain power. The imagination, however, helps us see beyond these “mind forg’d manacles” (to cite William Blake’s “London”) to new human possibilities.

Great poetic imaginations do not do this on a superficial level but, in Wordsworth’s words, help us “see into the life of things” (Tintern Abbey).

I find myself returning to philosopher John Stuart Mill, whom I encountered in a college ethics class. Although a utilitarian who believed in finding ways to do the greatest good for the greatest number, he found the utilitarianism of a figure like Jeremy Bentham to be sterile, a kind of ethical algebra. It’s as though one needs to be a passionless accountant to distribute society’s resources (not that they ever get evenly distributed). A literary example of a utilitarian is Gradgrind in Hard Times, who sees everything in terms of social utility and regards fantasy and the world of the circus as pointless. When he was a young man being raised by a utilitarian father, Mill had a mental breakdown and it took poetry to pull him out.

Poetry, as Mill saw it, can change our hearts and minds as mere rational self-interest cannot. Thus, although imagination and poetry seem to take us out of the world—this is certainly Gradgrind’s view—it actually allows us to engage more effectively with it.

I’m particularly interested in how it helps us imagine a freer and more egalitarian society and a healthier relationship with our natural environment. As an example of the first, there’s the poetry of Walt Whitman, whose soaring free verse in Song of Myself helps show America how to live up to the vision expressed in The Declaration of Independence. Whitman bestows humanity on everyone, including escaped slaves, Native Americans, backwoodsmen, and other marginalized populations. Seeing himself as standing in for America, Whitman memorably declares, “I contain multitudes.” Whitman doesn’t only show what a diverse and multicultural society looks like. Through his imagination, he sweeps us up so that we feel the power and excitement of such a society.

Literature does the same for the natural world, as countless poems and stories in literary history have demonstrated. Some works demonstrate the cost of being alienated from the natural world (Euripides’s The Bacchae, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Wordsworth’s “The World Is Too Much with Us”), others the gifts that it imparts. Given that how we interact with nature in the upcoming decades will determine the fate of humankind, I should have a chapter on how literature can help us negotiate this particular challenge. Perhaps there’s a good essay by Wendell Barry that has thought through these issues more systematically than I have.

Obviously, much more to come. Please write in with any suggestions you have.