Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Friday

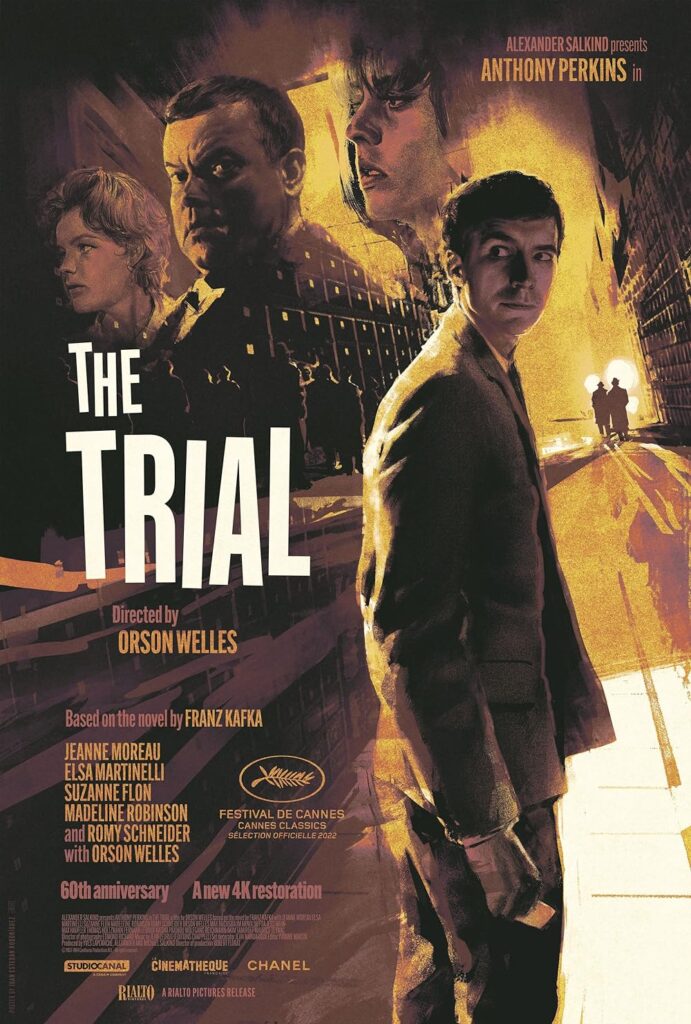

Washington Post satirist Alexandra Petri has once again hit paydirt by imagining Donald Trump as the protagonist of Kafka’s The Trial. While Trump himself, being a non-reader, would not describe his experiences as Kafkaesque, some of his more literate supporters might.

Of course, the big difference is that K. never discovers what he’s been accused of—that’s what makes the novel so nightmarish—whereas the Trump indictments are clearly spelled out: he stole documents, he defrauded banks, he attempted to overthrow the government, he slimed a woman that he raped. Petri pulls off her satire, however, by showing the whole trial through Trump’s eyes. From that vantage point, Trump is just as confused as K.

In The Trial, K. never finds a firm place on which to stand. It all starts with his arrest:

Someone must have been telling lies about Josef K., he knew he had done nothing wrong but, one morning, he was arrested. Every day at eight in the morning he was brought his breakfast by Mrs. Grubach’s cook—Mrs. Grubach was his landlady—but today she didn’t come. That had never happened before.

Then there’s this interchange with the arresting officers:

“And why am I under arrest?” he then asked. “That’s something we’re not allowed to tell you. Go into your room and wait there. Proceedings are underway and you’ll learn about everything all in good time.”

Later, when he shows up to court, he’s never clear what exactly is happening. The courtroom itself is hard to find and then, when he enters, he’s not sure what anyone’s role is:

At the other end of the hall where K. had been led there was a little table set at an angle on a very low podium which was as overcrowded as everywhere else, and behind the table, near the edge of the podium, sat a small, fat, wheezing man who was talking with someone behind him. This second man was standing with his legs crossed and his elbows on the backrest of the chair, provoking much laughter. From time to time he threw his arm in the air as if doing a caricature of someone. The youth who was leading K. had some difficulty in reporting to the man. He had already tried twice to tell him something, standing on tiptoe, but without getting the man’s attention as he sat there above him. It was only when one of the people up on the podium drew his attention to the youth that the man turned to him and leant down to hear what it was he quietly said.

And then there’s the judge:

[K.] stood pressed closely against the table, the press of the crowd behind him was so great that he had to press back against it if he did not want to push the judge’s desk down off the podium and perhaps the judge along with it.

The judge, however, paid no attention to that but sat very comfortably on his chair and, after saying a few words to close his discussion with the man behind him, reached for a little notebook, the only item on his desk. It was like an old school exercise book and had become quite misshapen from much thumbing. “Now then,” said the judge, thumbing through the book. He turned to K. with the tone of someone who knows his facts and said, “you are a house painter?” “No,” said K., “I am the chief clerk in a large bank.” This reply was followed by laughter among the righthand faction down in the hall…

There is one final interaction with this judge at the end of the chapter when K. defiantly turns to go:

“One moment,” [the judge] said. K. stood where he was, but looked at the door with his hand already on its handle rather than at the judge. “I merely wanted to draw your attention,” said the judge, “to something you seem not yet to be aware of: today, you have robbed yourself of the advantages that a hearing of this sort always gives to someone who is under arrest.” K. laughed towards the door. “You bunch of louts,” he called, “you can keep all your hearings as a present from me,” then opened the door and hurried down the steps. Behind him, the noise of the assembly rose as it became lively once more and probably began to discuss these events as if making a scientific study of them.

K doesn’t manage to maintain this bravado for long, however, and starts obsessing about his situation. It so happens that he never sees the judge again although he searches for him. He also seeks to learn about his legal situation from a lawyer, who never gives him a straight answer. In the end, the only certainty that K. finds is his own death.

Petri begins her piece by riffing on Kafka’s first line:

Someone must have been telling lies about Donald T. because he had done nothing wrong and yet he kept having to be on trial. He was on trail everywhere at once.

No, T. could think of no possible reason this would be happening to him. It was Kafkaesque! He had simply been going about his business like any other man, inflating his assets, demanding more votes to keep him in power, stockpiling classified documents in his bathroom — and now this strange thing was happening.

We soon learn the reasons for T.’s confusion: he thinks he’s at a rally:

T. knew that something was unusual when he arrived at his campaign rally. From the very first moment it struck him as an odd place for a rally. It was inside a Manhattan curtroom. His children had spoken, which was typical for a rally, but their remarks had been strangely confined to their business dealings. Instead of saying how great he was and how wonderful he was going to make America, they had said things about negotiations and used the word “boilerplate.”

In Kafka’s courtroom scene, K. tries explaining that a mistake has been made, only to be confused by the responses. Petri has the same situation play out with T.:

T. thought it best to deliver his rally speech as usual. He would certainly not be the one to admit that something was out of the ordinary. He would tell them about his hatred of windmills (“I’m not a windmill person” and how much he esteemed Mar-a-Lago, a place of incalculable value because it was the most beautiful spot in the world. He would tell them how he would be the next president, though perhaps it would be better not to elaborate on his plans to get vengeance right away. He would rail about witch hunts and judges. He started off quite strongly, but as he went on, he began to feel ill at ease. It was strange to speak like this without his cheering audience, with just the man sitting there at the desk growing visibly irritated.

Unlike Kafka, however, Petri actually shows straight answers being given to the defendant:

And this was not his only rally held in a tiny courtroom. He had to keep appearing in these places. He was on trial everywhere, all the time, and no one could tell him why. “That’s not true,” somebody said. “Everyone has been telling you why constantly. You are on trial in the state of New York for business fraud. You are on trial in Florida for your mishandling of classified documents. And you are on trial in Georgia for trying to overturn the election.”

Because he’s living in his own bubble, however, T. cannot hear what people are saying:

No, he could not understand it. He would simply refuse to understand it, and see what would happen then.

What happens then in The Trial is that K. K. is murdered by two state thugs. While we don’t want that for Trump, we do want some accountability.

Interestingly, for all people’s complaining about living in a Kafkaesque world, Trump is currently in court because America is not the society we see in The Trial. The court system is following a set of clearly set out rules so that everyone knows where they are at all times. For that matter, our electoral system keeps on reflecting the will of the voters, and our institutions of law enforcement, in the main, continue to work. And the mainstream media gets things mostly right.

If Trump gets his way, on the other hand, we really will have a Kafkaesque society where he can hound people who have done nothing wrong and twist the law to suit his own ends. Although The Trial was written in 1914-15, it resembles the world of Josef Stalin or Vladimir Putin, which we know is Trump’s dream. Increasingly we’re hearing about plans to stuff the Justice Department and the Federal Government with Trump sycophants should he regain the presidency.

The Republican House is already doing its part, seeking to impeach Joe Biden for reasons to be decided later. We’re not out of the woods yet.