Tuesday

With my mother’s death, I am reminded that we all grieve differently and that one person’s grieving may rub another person the wrong way. My own grieving for my mother has taken the form of intense busyness: for weeks I have been working simultaneously on preparing for the memorial service while putting her house in order. But whereas I wanted to distribute as much of her worldly goods to my brothers and other relatives as I could when they showed up, one of these brothers and one of my sons wanted to focus soley on their sadness and postpone matters of property division to another day. Once I realized that we were all grieving in our own particular ways, I felt better about the anger I encountered.

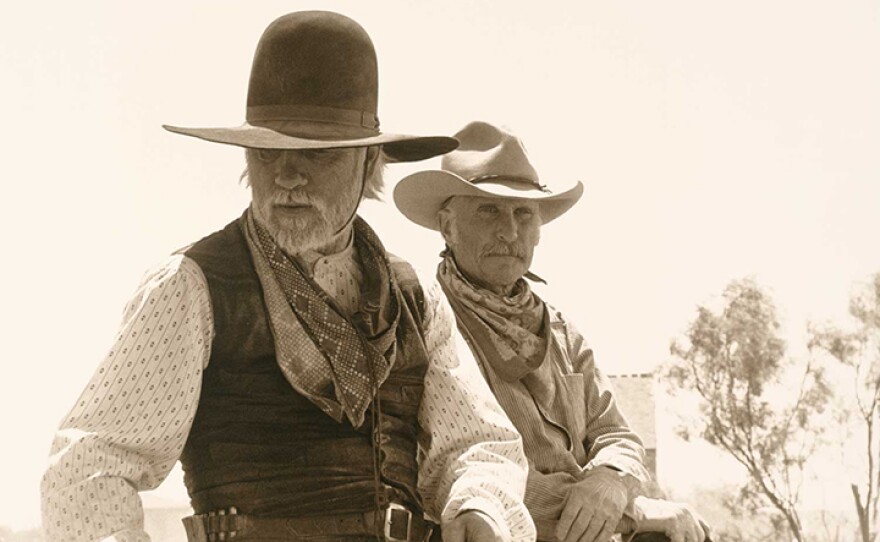

I compare my own path with that taken by Captain Woodrow Call in Larry McMurtry’s western Lonesome Dove. Call is one of two legendary Texas rangers who is outliving the heroic age of the wild west. In an epic trek, he and fellow ranger Augustus McCrae have taken a herd of cattle from Texas to the fertile grazing lands of Montana. In doing so, however, they have tamed the west even more, making themselves even more irrelevant. As Gus puts it before he dies of a gangrenous leg caused by an Indian arrow, “Look there at Montana. It’s fine and fresh, and now we’ve come and it’ll soon be ruint, like my legs.”

Because Gus understands his partner well, he makes an outrageous deathbed request: he wants Call to reverse his trek and bury Gus’s body where they started out, in Lonesome Dove, Texas. Call can’t believe what he’s heard but Gus explains his reasoning:

“My God,” Call said, thinking his friend must be delirious. “You want me to haul you to Texas? We just got to Montana.”

“I know where you just got,” August said. “My burial can wait a spell. I got nothing against wintering in Montana. Just pack me in salt or charcoal or what you will. I’ll keep well enough and you can make the trip in the spring. You’ll be a rich cattle king by then and might need a restful trip.”

Call looked at his friend closely. Augustus looked sober and reasonably serious.

“To Texas?” he repeated.

“Yes, that’s my favor to you,” August said. “It’s the kind of job you was made for, that nobody else could do or even try. Now that the country is about settled, I don’t know how you’ll keep busy, Woodrow. But if you’ll do this for me you’ll be all right for another year, I guess.”

Gus then jokingly worries that Call may die of boredom before he sets out, in which case Gus will have to settle for a Montana grave.

While Call’s 3000-mile journey back to Texas is not quite as epic as the journey to Montana, it poses serious challenges. Before he’s done, the buggy carrying the body has fallen apart, the donkey pulling it has died, and the coffin, almost lost in a river crossing, is leaking salt. Towards the end, Call must bundle the body in a tarp and drag it travois style behind his horse. At one point he is also shot by an Indian so that he has a leaking wound when he finally arrives back at Lonesome Dove. He may not live much longer.

Gus, however, has achieved his major aim: which is not to be buried in Texas but to give Call the way to mourn that suits him best.

I don’t know if intense busyness has been the best way to mourn my mother, but I feel that it has kept me going. Now that the family has dispersed and my responsibilities have diminished, I’m experiencing a void, somewhat like Call at the end of his second trek.

But it’s a void that now seems bearable.