Spiritual Sunday

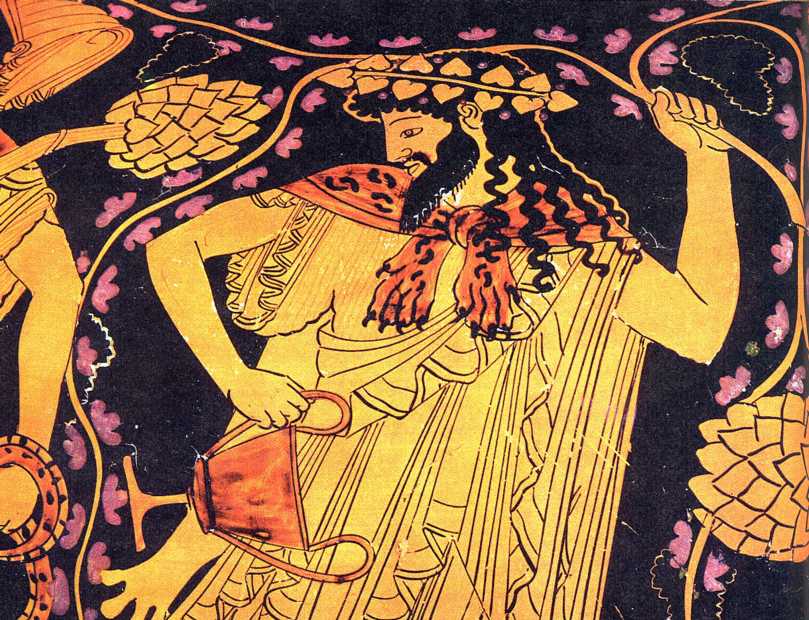

Today’s lectionary reading—the parable of Jesus as the “true vine”—reminds me of a passage from Euripides’ The Bacchae. Translator Michael Cacoyannis, the Greek filmmaker, emphasizes certain parallels between Jesus and Dionysus in ways that get us to see the passage from John in new ways. First, here’s John:

Jesus said to his disciples, “I am the true vine, and my Father is the vinegrower. He removes every branch in me that bears no fruit. Every branch that bears fruit he prunes to make it bear more fruit. You have already been cleansed by the word that I have spoken to you. Abide in me as I abide in you. Just as the branch cannot bear fruit by itself unless it abides in the vine, neither can you unless you abide in me. I am the vine, you are the branches. Those who abide in me and I in them bear much fruit, because apart from me you can do nothing. (John 15:1-5)

And now here’s Euripides, writing 500 years earlier. Like Jesus, Dionysus was born of a virgin impregnated by a god (Zeus). Some religious scholars believe that the story of the resurrection grew out of Dionysian fertility cults while others think that early Christians compared Jesus to Dionysus/Bacchus in order to elevate their new religion:

Next [after earth goddess Demeter] came the son of the virgin, Dionysus,

bringing the counterpart to bread, wine

and the blessings of life’s flowing juices.

His blood, the blood of the grape,

lightens the burden of our mortal misery.

When after their daily toils, men drink their fill,

sleep comes to them, brining release from all their troubles.

There is no other cure for sorrow. Though himself a God,

it is his blood we pour out

to offer thanks to the Gods. And through him,

we are blessed.

A later passage brings Pentecost to mind:

This God is also a prophet. Possession by his ecstasy,

his sacred frenzy, opens the soul’s prophetic eyes.

Those whom his spirit takes over completely

often with frantic tongues foretell the future.

There’s also this:

He is life’s liberating force.

He is release of limbs and communion through dance.

He is laughter and music in flutes.

He is repose from all cares—he is sleep!

When his blood bursts from the grape

and flows across tables laid in his honor

to fuse with our blood,

he gently, gradually, wraps us in shadows

of ivy-colored sleep.

Like Jesus, Dionysus offends the authorities in charge of law and order, who take particular offense to his female followers. In one scene, King Pentheus becomes a Pontius Pilate figure, passing judgment on an unresisting Dionysus. We see Pentheus’s rage against this rabble rouser earlier in the play:

The rest of you,

scour the city, find this effeminate stranger

who afflicts our women with this new disease

and who befouls our beds. And when you catch him,

drag him here in chains.

He’ll taste the people’s justice when he’s stoned to death,

regretting every bitter moment of his fun in Thebes.

I don’t want to push the parallels too far because Christianity took Dionysian rituals in a less earthly direction, proclaiming as heretics those who advocated for a more sensual Christ. Also Jesus, unlike Dionysus, does not insist upon vengeance.

Nevertheless, we can see why people found the Eucharist drama so compelling. By the time of the Last Supper, there was already a long mythic history of wine as a metaphor for a god’s life-sustaining blood.