Wednesday

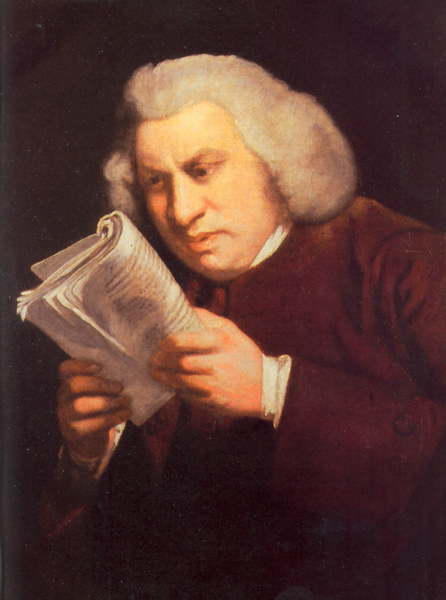

Yesterday, while reading Samuel Johnson’s preface to The Plays of William Shakespeare (1765), I was reminded that the 18th century would not have objected to the premise of my blog. It is later schools of criticism that have bristled over the notion that literature is supposed to help us lead better lives.

Romantic poets and 19th century novelists worried at how utility was becoming the measure of all things (see Dickens, Hard Times). Often they regarded literature as a refuge from the values of money-grubbing industrial capitalism. Horrified at how workers were being reduced to instruments, poetry elevated the imagination to counter the descent into materialism.

The same was true of the 1950s when literary scholars, reacting against consumer capitalism, approvingly quoted Sidney’s “the poet, he nothing affirmeth,” W. H. Auden’s “poetry makes nothing happen,” and William Carlos Williams’s

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

Poetry, in other words, is not narrowly pragmatic.

Samuel Johnson didn’t have these worries. For him, Shakespeare was a blessing to humankind because he made our everyday lives better. His plays are full of news about people.

Shakespeare was able to do this, Johnson believes, because he understood human nature better than any modern writer:

Shakespeare is above all writers, at least above all modern writers, the poet of nature; the poet that holds up to his readers a faithful mirror of manners and of life…His persons act and speak by the influence of those general passions and principles by which all minds are agitated, and the whole system of life is continued in motion. In the writings of other poets a character is too often an individual; in those of Shakespeare it is commonly a species.

This in turn means that “much instruction” is to be gained from encounters with the Bard:

It is from this wide extension of design that so much instruction is derived. It is this which fills the plays of Shakespeare with practical axioms and domestic wisdom. It was said of Euripides, that every verse was a precept; and it may be said of Shakespeare, that from his works may be collected a system of civil and economical prudence.

Later in the preface Johnson repeats the idea, noting,

From his writings indeed a system of social duty may be selected.

Johnson goes on to say that individual passages from Shakespeare don’t accomplish this as much as what is communicated through the unfolding of the stories and through dialogue:

Yet his real power is not shown in the splendor of particular passages, but by the progress of his fable, and, the tenor of his dialogue; and he that tries to recommend him by select quotations, will succeed like the pedant in Hierocles, who, when he offered his house to sale, carried a brick in his pocket as a specimen.

In other words, don’t quote Polonius’s “to thine own self be true” advice to Laertes if you want to honor Shakespeare’s guiding wisdom. Rather, watch how characters respond to the pressures of the moment and how they talk to others. Or as Johnson explains further on,

Shakespeare has no heroes; his scenes are occupied only by men, who act and speak as the reader thinks that he should himself have spoken or acted on the same occasion: Even where the agency is supernatural the dialogue is level with life…Shakespeare approximates the remote, and familiarizes the wonderful; the event which he represents will not happen, but if it were possible, its effects would be probably such as he has assigned; and it may be said, that he has not only shown human nature as it acts in real exigencies, but as it would be found in trials, to which it cannot be exposed.

According to Johnson, by reading Shakespeare’s “human sentiments in human language,” a hermit would be able to figure out what is going on in the world and a confessor would be able to predict where the human passions will lead.

Johnson has some blindnesses. Most notoriously, he saw nothing of use in King Lear’s bleak conclusion, which he found unbearably nihilistic. He was so traumatized by the death of Cordelia that he actually approved of Nahum Tate’s replacement ending where Cordelia survives and marries Edgar.

But we today can gain insights from the bleak ending and, for that matter, from how traumatized Johnson was by it. To acknowledge that the world can at times be this dark provides us with a truth that challenges us.

It’s not the only truth, however. Shakespeare may offer us no reassurance in King Lear, but luckily one play and one author don’t get the final word, as I argued last week. Other works and other writers can come to our aid.

One last point: in his preface Johnson courageously went against some of the prevailing assumptions about drama, including the ideas that comedy and tragedy cannot be mixed and that drama must follow the three unities of action, place and time. Shakespeare violates all these “rules” (except for unity of action), and Johnson argues that the wisdom in his plays brings those very rules into question.

As Johnson sees it, Shakespeare mingling tragedy and comedy is another instance of him being true to human nature. Johnson cites Horace’s maxim that literature instructs by pleasing and believes we find Shakespeare delightful because he understands us so well:

That [mingling tragedy and comedy] is a practice contrary to the rules of criticism will be readily allowed; but there is always an appeal open from criticism to nature. The end of writing is to instruct; the end of poetry is to instruct by pleasing. That the mingled drama may convey all the instruction of tragedy or comedy cannot be denied, because it includes both in its alterations of exhibition, and approaches nearer than either to the appearance of life, by showing how great machinations and slender designs may promote or obviate one another, and the high and the low co-operate in the general system by unavoidable concatenation.

Or put another way, we are complex mixtures of the tragic and the comic and of high and low. Shakespeare understood this far better than many of his critics. His plays teach us the truth.