As I teach Stephen King’s IT in my American Fantasy course, I’ve become fascinated by his allusions to an epic poem written by William Carlos Williams. King has multiple epigraphs for the different sections of his book, and five of those epigraphs are taken from Paterson. King’s references to Williams help clarify my sense that King dreams America’s nightmares. For Williams, a place defines a people, and King’s fictional city of Derry, Maine has a corrupt foundation that taints everything connected with it.

In past posts on IT, I’ve examined America’s penchant for violence and how America seeks to whitewash its dark history. Today I focus on those forces that are threatening the environment.

Williams famously wrote “no ideas but in things,” and the thing/place he chooses to explore in his five volume poem is Paterson, New Jersey. The central image of the poem, Williams notes, is of “the city as a man, a man lying on his side peopling the place with his thoughts.”

Paterson, as Williams sees it/him, is defined by two conflicting American strains: a paranoid, acquisitive Puritan strain and an open-minded, inquisitive strain that Williams associates with the French Jesuit missionary Father Rasles. Williams scholar Walter Scott Peterson lays out the contrast:

The “Puritans,” most simply, symbolize the kind of mind which, pursuing only pragmatic ends, views the world with mistrust or even fear. Such a mind seeks to isolate itself by retreating into conventionality and solipsism. Rasles and Williams’ other heroes, on the contrary, symbolize the kind of mind which, pursuing only the wonder and beauty freely given by its local surroundings, views the world with trust and courage. Through love and imagination such a mind seeks a mutual relationship with its world that is both vital and creative.

In IT, Derry fits the Puritan mold, although only a few sensitive adults sense that something is rotten at the core. The rottenness becomes apparent when one looks into Derry’s history, which includes a horrific treatment of the environment. King describes the clear-cutting of Maine’s “virgin” forests as a rape:

The other members of the [Library] Board are the descendants of the lumber barons. Their support of the library is an act of inherited expiation: they raped the woods and now care for these books the way a libertine might decide, in his middle age, to provide for the gaily gotten bastards of his youth. It was their grandfathers and great-grandfathers who actually spread the legs of the forests north of Derry and Bangor and raped those green-gowned virgins with their axes and peaveys. They cut and slashed and strip-timbered and never looked back. They tore the hymen of those great forests open when Grover Cleveland was President and had pretty well finished the job by the time Woodrow Wilson had his stroke. These lace-ruffled ruffians raped the great woods, impregnated them with a litter of slash and junk spruce, and changed Derry from a sleepy little ship-building town into a booming honky-tonk where the ginmills never closed and the whores turned tricks all night long.

And further on:

So that was Derry right through the first twenty or so years of the twentieth century: all boom and booze and balling. The Penobscot and the Kenduskeag were full of floating logs from ice-out in April to ice-in in November. The business began to slack off in the twenties without the Great War or the hardwoods to feed it, and it staggered to a stop during the Depression. The lumber barons put their money in those New York or Boston banks that had survived the Crash and left Derry’s economy to live—or—die—on its own. They retreated to their gracious houses on West Broadway and sent their children to private schools in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and New York. And lived on their interest and political connections.

Today, our versions of these timber barons are the Koch Brothers and other fossil fuel magnates, who seek to do away with environmental regulations (which means buying the politicians who will do so) so that they can open up the country to unfettered fracking, tar sand oil extraction, pipeline construction, unfiltered coal emissions, and the like. As a result, we are seeing a marked increase in oil wells exploding, train cars catching fire, oil tankers foundering, pipelines rupturing, and coal ash ponds polluting major waterways. Meanwhile fracking, which is occurring even in residential areas and national parks, is leading to earthquakes and groundwater contamination. King’s maniac clown is on the loose.

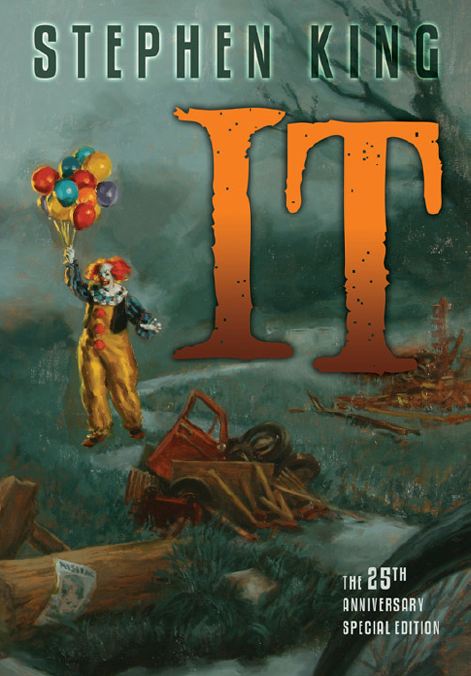

Both Williams and King look to love and imagination as the forces that must stand up to the devastation. In King’s novel, these are found in the children, whose minds have not yet been colonized by the adults. I’ll talk about how they defeat the clown next week.

One Trackback

[…] King’s Vision of Environmental Devastation […]