It makes my day to see a sports essay quote Kipling: in a superb ESPN Grantland piece, Brian Phillips recently compared Kobe Bryant to Akela, the “Lone Wolf” and leader of the pack in The Jungle Books. The comparison is even more apt and holds more lessons than Phillips realizes.

Phillips notes how Bryant has always thought that he can do everything by himself. Now, however, his image of himself is foundering on the shoals of reality. Bryant’s skills have diminished and the players around him are not very good, with the result that the Lakers are one of the worst teams in the NBA. Nevertheless Bryant appears to think that, if he keeps on taking shot after shot, he can singlehandedly will the Lakers to victory. Here’s Phillips describing his mentality:

This season is the distillation of the go-it-alone challenge Kobe set for himself back when O’Neal and Phil Jackson left L.A., or even sooner — Kobe, remember, is the star player who invited none of his teammates to his wedding. (It’s a wonder he invited his wife.) He can’t win, a fact that has no apparent bearing on the fury with which he is trying. We’re seeing Kobe stripped of everything except the will to succeed, a will that persists despite being hopeless. We’re seeing him face his doom with a fearlessness that is ludicrous, profane, and maybe slightly inspiring. We’re seeing the existential Kobe Bryant.

And now here’s Phillips quoting Kipling:

A few months ago, I read The Jungle Book to my 8-year-old niece. She listened with huge eyes to Kipling’s story of talking wolves and vengeful tigers and the Law of the Jungle; as soon as we were finished, she demanded to hear it again. One of the places where her eyes got biggest was the part about Akela, the Lone Wolf, who rules the pack from atop the Council Rock. Do you remember this? It’s silly, like Kobe Bryant, and also kind of moving, like Kobe Bryant. Akela is strong and cunning. But he knows that one day he must lose his strength, and that when that happens, the young wolves will challenge him and pull him down and kill him — which, of course, nearly happens in the course of the story. There’s a lot of talk in basketball about players who are alpha dogs; an October 2013 Sports Illustrated cover depicted Kobe as the last of the breed. But ask my niece what happens when alpha dogs reach the end.

The passage from Jungle Books is actually more complicated that this. As Phillips sees it, Kipling’s Law of the Jungle simply describes what happens to every athlete when he or she gets old. Bagheera sums up succinctly the ruthless hand of Father Time:

Akela is very old, and soon the day comes when he cannot kill his buck, and then he will be leader no more.

To my great sadness, Peyton Manning too may have reached the point where he is unable to kill many more bucks.

Kipling doesn’t stick with the Law of the Jungle as he describes it, however. First of all, while acknowledging that Akela can’t do what he used to, Kipling complains that Akela is brought down by a trick. The tiger Shere Khan, exerting an unhealthy influence on the young wolves, has persuaded them to set up a trap for Akela. The Lone Wolf explains to the pack what has happened:

Free People, and ye too, jackals of Shere Khan, for twelve seasons I have led ye to and from the kill, and in all that time not one has been trapped or maimed. Now I have missed my kill. Ye know how that plot was made. Ye know how ye brought me up to an untried buck to make my weakness known. It was cleverly done. Your right is to kill me here on the Council Rock, now. Therefore, I ask, who comes to make an end of the Lone Wolf? For it is my right, by the Law of the Jungle, that ye come one by one.

Kipling is trying to have the law of the jungle both ways here, holding it up as deep wisdom yet also looking for ways around it. There’s something to be said for the ruthlessness of the law, which allows for fresh leadership. Because Akela’s skills have slipped, he can’t enforce discipline over the younger wolves anymore. Shere Khan wouldn’t have any influence over them if Akela were still in his prime. In other words, by hanging on too long, Akela has helped create the situation that brings him down.

In another violation of the Law, Kipling seems to approve of Mowgli resorting to fire to save Akela. In a sports context, this sounds suspiciously like an owner overriding a general manager to retain a superstar whose time has passed. If the Law of the Jungle is all knowing, then trickery should neither be able to speed it up nor delay it.

Part of the problem is with the Law’s criteria. If it only insists on the buck test, then it overlooks other ways in which a leader contributes. Only after Akela jumps to the Mowgli team and goes off to kill Shere Khan do the young wolves discover how much they relied on him:

Ever since Akela had been deposed, the Pack had been without a leader, hunting and fighting at their own pleasure. But they answered the call [to come see Shere Khan’s hide] from habit; and some of them were lame from the traps they had fallen into, and some limped from shot wounds, and some were mangy from eating bad food, and many were missing.

Do you see where I’m going with this? Kobe Bryant thinks he needs to kill bucks to be the leader whereas there might be other roles he can fill. He refuses to adjust and, as a result, other teams are swarming around him with their teeth bared.

The result is not pretty although Phillips finds it fascinating. At the very least, Bryant is being true to who he is:

Kobe is alienating because he doesn’t care about dignity. If preserving his sense of who and what he is means ending his career loudly and embarrassingly, he will be as loud and embarrassing as he can. He has severed his ties, imperiously, with the support systems that keep other great players respectable after their skills erode — with teammates, coaches, and executives who could help mask his weaknesses and fawn over him in the press. …The role Kobe is playing is one he created for himself. He is showing us what happens when an alpha dog dies ungracefully, the way alpha dogs are supposed to die. It is hilarious and painful to watch, and probably to live, too, although who knows? It can’t be easy.

The end, as Phillips suggests, does not have to be undignified. For an alternative ending, we can turn to Tim Duncan of the San Antonio Spurs. Think of him as Akela in the fight against the Red Dogs, described in the second Jungle Book.

The Red Dogs are an unstoppable force that kill everything in their path. Mowgli manages to outwit them, however, by running them into an enormous beehive so that they leap off a cliff. Those who survive the fall are finished off by the wolf pack in the river below.

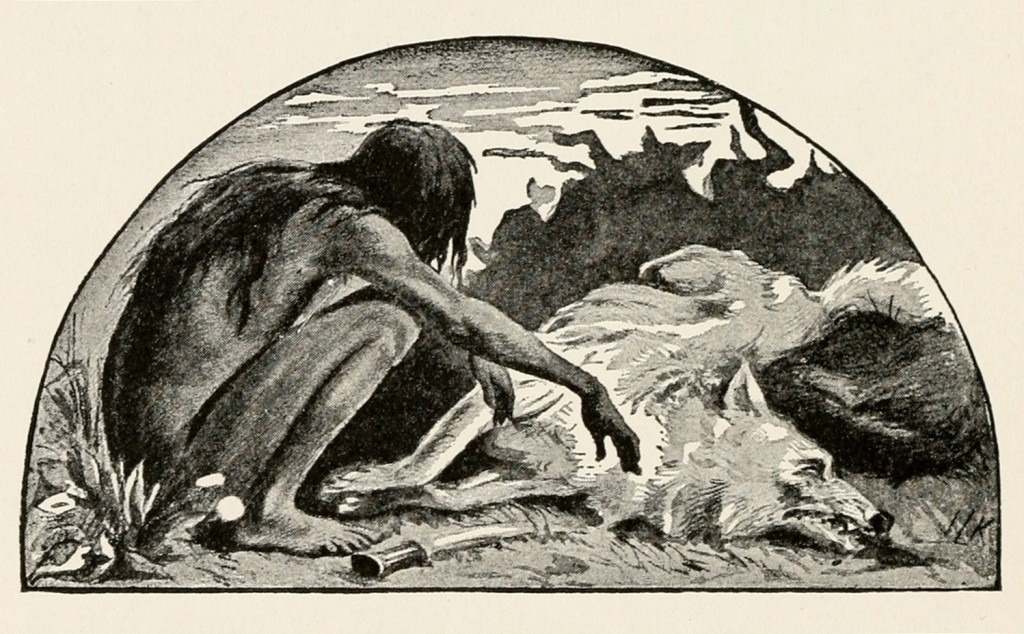

Akela, who has essentially turned the pack over to Mowgli by this point, dies in this last great battle. His death is noble and heroic:

“There is no more to say,” said Akela. “Little Brother, canst thou raise me to my feet? I also was a leader of the Free People.”

Very carefully and gently Mowgli lifted the bodies aside, and raised Akela to his feet, both arms round him, and the Lone Wolf drew a long breath, and began the Death Song that a leader of the Pack should sing when he dies. It gathered strength as he went on, lifting and lifting, and ringing far across the river, till it came to the last “Good hunting!” and Akela shook himself clear of Mowgli for an instant, and, leaping into the air, fell backward dead upon his last and most terrible kill.

Duncan, unlike Bryant, has turned the alpha dog role over to others and become an important part of a collective effort. The result last year was another NBA title. Even if there had been no championship, there would still have been dignity.

Kobe is made of different stuff, and it appears he will prove to be a true Lone Wolf down to the very end.