Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Friday

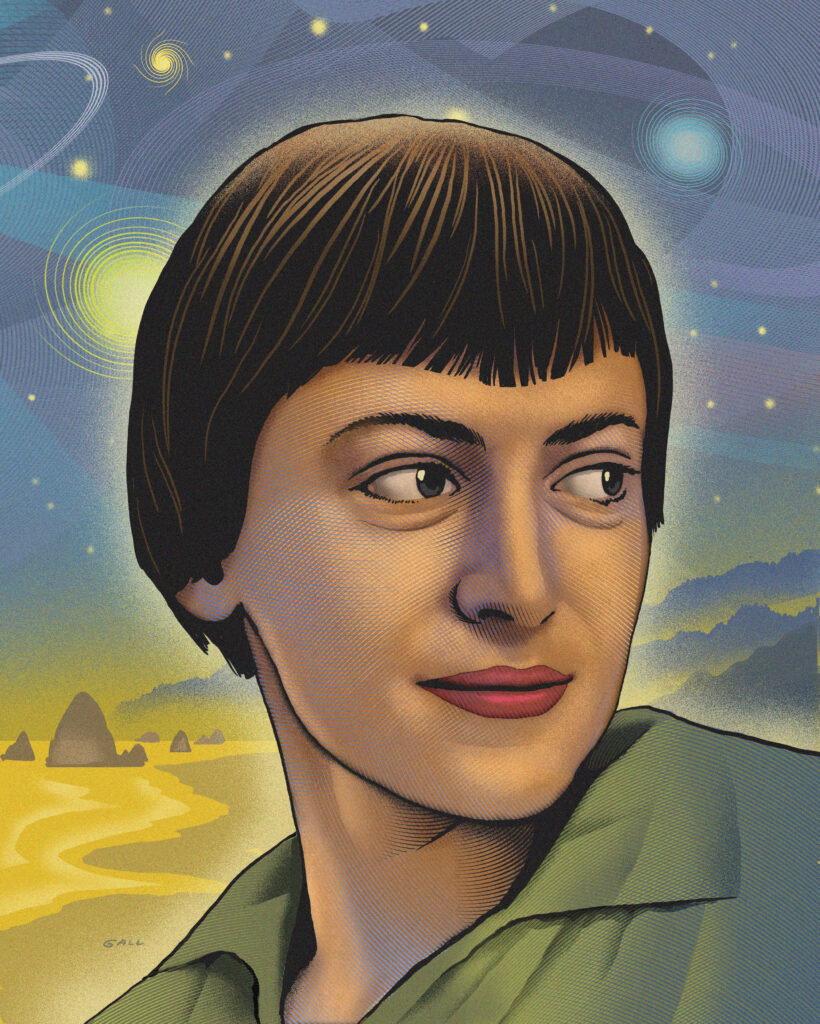

A recent Literary Hub article on Ursula Le Guin’s activism grapples with how to respond to Trumpism’s recent victory, with Julie Phillips looking back over the author’s life and works for anything useful.

Phillips begins with Le Guin’s response to Trump’s first victory in 2016. “Americans have voted for a politics of fear, anger, and hatred,” Le Guin observed, and her fear was that liberals like her would fall into a vicious circle of action and reaction. It’s something that happens in The World for Word Is Forest, where the peaceful Athsheans live in accord with nature until aggressive earthlings invade them in a search for natural resources. Although they manage to repel the invaders, they are tainted by the experience, learning that it is possible to kill without reason.

As she processed Trump’s victory, Le Guin wrote that she was looking “for a place to stand, or a way to go, where the behavior of those I oppose will not control my behavior.” In her case, she turned to Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching, advocating his “paradoxical ideal” of “doing without doing”:

[S]he advised standing firm, “refusing to engage an aggressor on his own terms.” Instead of fighting back, she counseled patience, compassion, and courage. “Defending a cause without fighting, without attacking, without aggression,” she argued, “is an action. It is an expression of power. It takes control.”

For a concrete example, she turned to water, which

gives way to anything harder than itself, offers no resistance, flows around obstacles, accepts whatever comes to it,…yet continues to be itself and to go always in the direction it must go. The tides of the oceans obey the moon while the great currents of the open sea keep on their ways beneath. Water remains itself and pursues its course, flowing down and on, above ground or underground, breathing itself out into the air in evaporation, rising in mist, fog, cloud, returning to earth as rain, refilling the sea. Water doesn’t have only one way. It has infinite ways, it takes whatever way it can, it is utterly opportunistic, and all life on earth depends on this passive, yielding, uncertain, adaptable, changeable element.

Phillips acknowledges herself somewhat frustrated by this response—it’s too vague and mystical for her—so she turns to how Le Guin actually lived her beliefs, along with what her fiction reveals. In The Dispossessed, for instance, she describes an anarchist community that has turned its back on capitalism and found another way to live. To reread The Dispossessed during the closing days of the 2024 election, Philips says,

was to take a restful vacation from billionaire oligarchs and election stress. On Anarres there are no politicians, no bosses, no wages, no police, “no law but the single principle of mutual aid between individuals” and “no government but the single principle of free association.” Its goals aren’t in the future—what we can achieve someday, when we run the perfect campaign or elect the perfect candidates—but in the process itself. Its people practice a politics of means, not ends.

While the Anarresti have only one word for “work” and “play,” Phillips notes, they do have a special word for drudgery (kleggich), which involves “the necessary tasks that keep households and societies running.” Le Guin, she points out, devoted much of her life to “small actions to support her city and its communities.” She also participated in various elections, stuffing envelopes and writing newsletters for Eugene McCarthy (in 1968) and, over the years, giving benefit reading “for bookstores, writers’ retreats, a women’s shelter, against hunger, censorship, AIDS.”

The idea of small actions making a difference is embraced in her well-known short story “The Ones Who Talk Away from Omelas,” a parable where certain citizens choose to walk away from their utopian society because this society can only exist if a child is mistreated. The parable applies to any society that exploits a few for the benefit of the many.

Phillips reports that Le Guin originally considered having people come in and save the child, even though in doing so they would render the rest of society unhappy. It’s noteworthy that, in her final version as in Dispossessed, she has people leave rather than strive to rectify the injustice.

While this may sound escapist, there’s something important that Le Guin is doing, which is using her fiction to imagine other possibilities for society. In my book Better Living through Literature I talk about how Marxist literary theorist Fredric Jameson praises Le Guin and certain other science fiction authors for this imagining:

Jameson [believes] that, if we have difficulty imagining a better world, it is “not owing to any individual failure of imagination but as the result of the systemic, cultural, and ideological closure of which we are all in one way or another prisoners.” In other words, those in power limit our very ability to imagine….

In his writing Jameson contends that utopian science fiction such as Dispossessed, Joanna Russ’s Female Man, Marge Piercy’s Women on the Edge of Time, and Samuel Delany’s Triton can counter this closure. He writes that their “deepest vocation is to bring home, in local and determinate ways, and with a fullness of concrete detail, our constitutional ability to imagine Utopia itself.”

In other words, by immersing ourselves in literary sci-fi, we begin chipping away at the impediments to imagining, thereby creating a space for radical aspiration. It’s a way of keeping our hope muscles from atrophying.

In her Literary Hub article, Phillips writes about a 1982 interview by a science fiction magazine where Le Guin was asked what she would do to save the world. She impatiently replied,

The syntax implies a further clause beginning with if…What would I do to save the world if I were omnipotent? But I am not, so the question is trivial. What would I do to save the world if I were a middle-aged middle-class woman? Write novels and worry.

To which Phillips adds, “If ‘worry’ can be translated as ‘care,’ then she combined her vision for the future with tending to what is worthy of care in the here and now.”

In short, Le Guin maintains a healthy balance between tending to local projects “while still writing and listening to the voices of writers who ‘can see alternatives to how we live now, and can see through our fear-stricken society … to other ways of being.’”

A novelist may not be able to tell us exactly what to do in the fact of a Donald Trump–Le Guin in fact shies aways from being didactic in her novels–but he or she\ helps prevent us from succumbing to his version of the world. While the fascist mentality seeks to limit what we see as possible, works like Dispossessed and “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” expand our horizons.