Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share it with anyone else.

Thursday

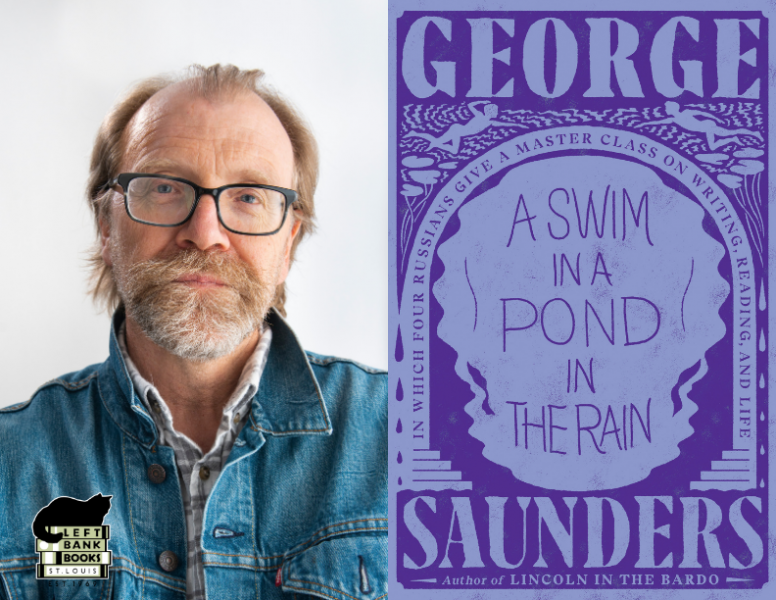

I just stumbled across George Saunders’s A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading and Life (2021). Since (as you well know) I’m a sucker for those who write about literature’s life lessons, I just had to hear what the Booker-winning novelist’s had to say on what Ivan Turgenev, Anton Chekhov, Leo Tolstoy, and Nikolai Gogol can teach us.

Swim in a Pond is itself a master class, based on a course that Saunders teaches to aspiring writers. As such, it functions as a “workbook” (Saunders’ description), and the author regularly interrupts the stories he’s anthologized with questions about how we are responding.

He observes that those stories, while quiet, domestic, and apolitical, can at the same time be regarded as “resistance literature, written by progressive reformers in a repressive culture, under constant threat of censorship, in a time when a writer’s politics could lead to exile, imprisonment, and execution.” The resistance in the stories, he explains, is

quiet, at a slant, and comes from perhaps the most radical idea of all: that every human being is worthy of attention and that the origins of every good and evil capability of the universe may be found by observing a single, even very humble, person and the turnings of his or her mind.

To offer a personal example of how such works can impact a life, he recounts his experience with (not so apolitical) Grapes of Wrath, which he read while holding down a brutal summer job in a Texas oil field as a “jug hustler”:

As I read Steinbeck after such a day, the novel came alive. I was working in a continuation of the fictive world, I saw. It was the same America, decades later. I was tired, Tom Joad was tired. I felt misused by some large and wealthy force, and so did Reverend Casy. The capitalist behemoth was crushing me and my new pals beneath it, just as it had crushed the Okies who’d driven through this same Panhandle in the 1930s on their way to California. We too were the malformed detritus of capitalism, the necessary cost of doing business. In short, Steinbeck was writing about life as I was finding it. He’d arrived at the same questions I was arriving at, and he felt they were urgent, as they were coming to feel urgent to me.

Saunders said that the Russian authors, when he encountered them a few years later, worked on him in the same way:

They seemed to regard fiction not as something decorative but as a vital moral-ethical tool. They changed you when you read them, made the world seem to be telling a different, more interesting story, a story in which you might play a meaningful part, and in which you had responsibilities.

At a time when various universities, regarding literature as “something decorative,” are reducing or even eliminating their humanities departments, Saunders shows us the colossal error of their ways. The aim of art, he says, is

to ask the big questions: How are we supposed to be living down here? What were we put here to accomplish? What should we value? What is truth, anyway, and how might we recognize it? How can we feel any peace when some people have everything and others have nothing? How are we supposed to live with joy in a world that seems to want us to love other people but then roughly separates us from them in the end, no matter what?

To which he adds, with a parenthetical wry smile,

(You know, those cheerful Russian kinds of big questions.)

To engage his students, Saunders teaches very much as I do in that he wants them to report on their interactions with the work. He makes clear there is no wrong answer (except, I suppose, claiming a reading experience you didn’t in fact have):

The basic drill I’m proposing here is: read the story, then turn your mind to the experience you’ve just had. Was there a place you found particularly moving? Something you resisted or that confused you? A moment when you found yourself tearing up, getting annoyed, thinking anew? Any lingering questions about the story? Any answer is acceptable. If you (my good-hearted trouper of a reader) felt it, it’s valid. If it confounded you, that’s worth mentioning. If you were bored or pissed off: valuable information. No need to dress up your response in literary language or express it in terms of “theme” or “plot” or “character development” or any of that.

If we study the way we read, he explains, we will become alert to how we process reality. Or as he puts it:

To study the way we read is to study the way the mind works: the way it evaluates a statement for truth, the way it behaves in relation to another mind (i.e., the writer’s) across space and time. What we’re going to be doing here, essentially, is watching ourselves read (trying to reconstruct how we felt as we were, just now, reading). Why would we want to do this? Well, the part of the mind that reads a story is also the part that reads the world; it can deceive us, but it can also be trained to accuracy; it can fall into disuse and make us more susceptible to lazy, violent, materialistic forces, but it can also be urged back to life, transforming us into more active, curious, alert readers of reality.

Saunders also provides a reassuring observation for those concerned about all the assaults on books, libraries, and the humanities in general:

Over the past ten years I’ve had a chance to give readings and talks all over the world and meet thousands of dedicated readers. Their passion for literature (evident in their questions from the floor, our talks at the signing table, the conversations I’ve had with book clubs) has convinced me that there’s a vast underground network for goodness at work in the world—a web of people who’ve put reading at the center of their lives because they know from experience that reading makes them more expansive, generous people and makes their lives more interesting.

(Enthusiastic applause)