Friday

Last month in The New York Times, Libyan novelist Hisham Matar touted literature as a powerful response to authoritarianism. The ideas will not be new to readers of this blog, but it’s always good to see literature reaffirmed in a public forum.

While Matar begins by talking about how we may read literature to “know the world” (or as Emily Dickinson puts it, “to take us lands away”), he then reverses course and talks about the shock of recognition when the foreign becomes familiar:

But the most magical moments in reading occur not when I encounter something unknown but when I happen upon myself, when I read a sentence that perfectly describes something I have known or felt all along. I am reminded then that I am really no different from anyone else.

Perhaps that is the secret motive behind every library: to stumble upon ourselves in the lives and lands and tongues of others. And the more foreign the setting, the more poignant the event seems. For a strange thing occurs then: A distance widens and then it is crossed.

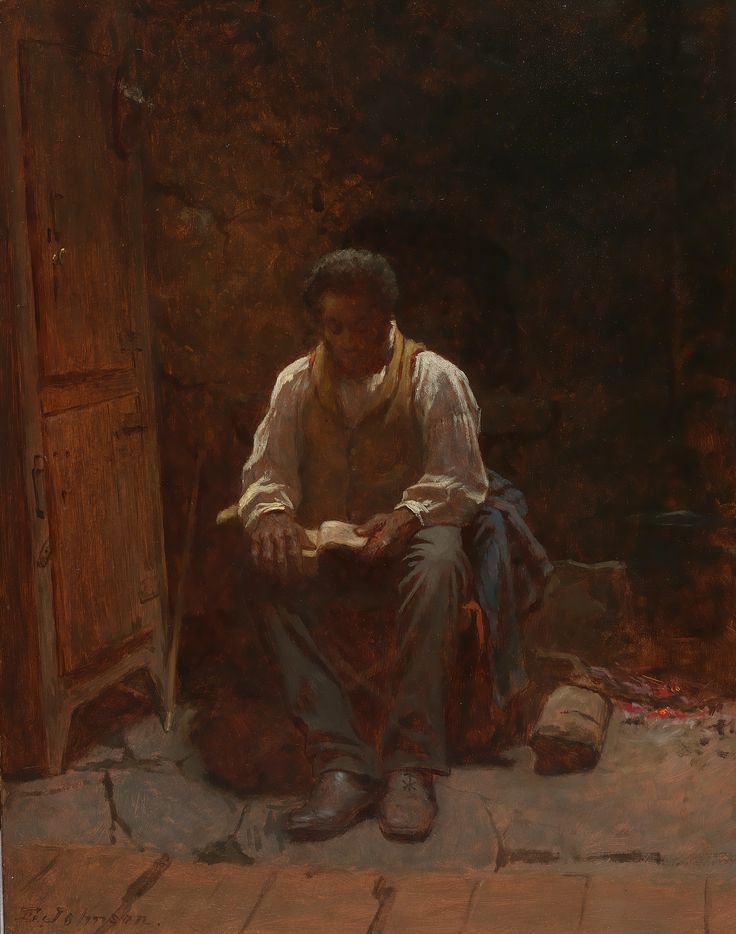

How many times, and in ways that did not seem to require my consent, have I suddenly and in my own bed found myself to be Russian or French or Japanese? How many times have I been a peasant or an aristocrat? How many times have I been a woman? I have been free and without liberty, gay, disabled, old, loved and loathed.

Matar is taking a universalist position here, asserting that “great literature has always flowed to the universal.” He sets up this universalism against the “narrow visions of right-wing populists such as Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, Geert Wilders and Nigel Farage.” Books, he says, can

develop our emotional, psychological and intellectual life, and, by doing so, show us how and to what extent we are connected.

This is why literature is the greatest argument for the universalist instinct, and this is why literature is intransigent about its liberty. It refuses to be enrolled, regardless of how noble or urgent the project. It cannot be governed or dictated to. It is by instinct interested in conflicting empathies, in men and women who are running into their own hearts, in doubt and contradictions. Which is why, without even intending to, and like a moon to the night, it disrupts the totalitarian narrative. What it reveals about our human nature is central to the conversation today.

In arguing for literature’s universalism, Matar takes issue with identitarianism, which argues that we can’t truly enter into the mindset of a different gender, ethnicity, nationality, etc. For identitarians, Matar says, “individual life is, first and foremost, representative of a racial, religious or cultural category.” In opposing this view, Matar aligns himself with Zimbabwean writer Dambudzo Marechera, who sees as narrowly provincial those who write “for a specific nation or a specific race.”

Philosopher Martha Nussbaum takes a similar view in“Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education.” Believing that literature is essential for creating “world citizens,” she writes,

The world-citizen view insists on the need for all citizens to understand differences with which they need to live; it sees citizens as striving to deliberate and to understand across these divisions. It is connected with a conception of democratic debate as deliberation about the common good. The identity-politics view, by contrast, depicts the citizen body as a marketplace of identity-based interest groups jockeying for power, and views difference as something to be affirmed rather than understood.

And further on:

An especially damaging consequence of identity-politics in the literary academy is the belief, which one encounters in both students and scholars, that only a member of a particular oppressed group can write well or, perhaps, even read well about that group’s experiences. Only female writers understand the experience of women; only African-American writers understand black experience. This claim has a superficial air of plausibility, since it is hard to deny that members of oppressed groups frequently do know things about their lives that other people do not know…But in general, if we want to understand the situation of a group, we do well to begin with the best that has been written by members of that group…We could learn nothing from such works if it were impossible to cross group boundaries in imagination.

Given that white identitarian politics have taken over the White House at the moment, universalism must be the left’s focus. I appreciate their concerns about universalism, and so does Nussbaum, who agrees that literary interpretation “is indeed superficial if it preaches the simplistic message that we are all alike under the skin.” We don’t have to see our choice as either-or, however.

When I read, I note both the points where I connect with characters and the points where I feel I’m missing something. That’s why we need diversity in college faculties. Those of us who teach older works negotiate the sameness-difference divide all the time, as I pointed out yesterday when my 18th century Couples Comedy class discussed Sense and Sensibility. While we relate to Elinor and Marianne in many ways, we also have to factor in their far more formal society and their rigid rules. Are our cultural differences with Austen or Shakespeare or the Beowulf poet greater than differences between various American ethnicities?

Negotiating sameness and difference in literature is not unlike what different activist groups must go through if they are to make common cause.

So think of literature’s universalism as an antidote to Trump’s exclusionary politics. Matar believes that Trump excludes because he does not understand, and therefore fears, multicultural complexity:

What false vigor then must demonizing and excluding millions of innocent people based on their race and religion inspire. And just like the censor who underestimates the common reader, Mr. Trump too has a limited interpretation of himself and therefore of humanity. And just like the censor, his actions will damage the fiber of his society because, in the long run, the more lasting damage falls on the one doing the excluding more than those being excluded.

If only Trump’s parents had read to him when he was a child.