Tuesday

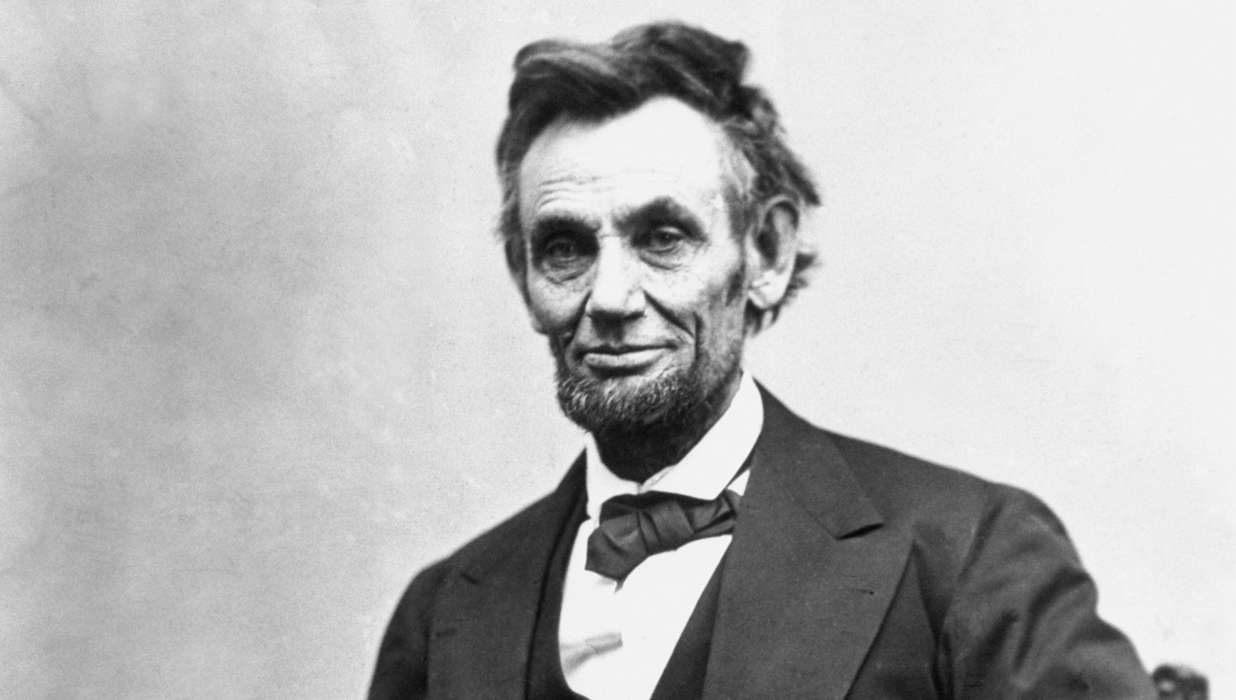

I’m currently reading a fascinating study about Lincoln’s Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness, recommended by my novelist friend Rachel Kranz. Among other things, author Joshua Wolf Shenk explores how Lincoln turned to literature to handle his mental illness and turn it into a source of strength.

Lincoln suffered unipolar depression for the entirety of his adult life. Shenk breaks his life into three stages: fear, engagement, and transcendence. While there were moments early on where the illness paralyzed him—“I am the most miserable man alive,” he wrote at one point—he figured out how to work with it when he entered politics. As Shenk puts it, whereas the first stage saw him trapped in a private hell,

the second stage has him turning to the world around him. From whether he could live, he turned to how he would live.

Lincoln’s greatness, Shenk believes, lay in how he was able to use his depression to his advantage. A man who hadn’t suffered as much and reflected as much might have been overwhelmed by the immensity of the Civil War. Suspicious of optimism, Lincoln had concluded that one should soldier on and do one’s duty, regardless of the hell one is experiencing:

In the first stage, he asked the big questions. Why am I here? What is the point? Without the sense of essential purpose he learned by asking these questions, he may not have had the bedrock vision that governed his great work. In the second stage, he developed diligence and discipline, working for the sake of work, learning how to survive and engage. Without the discipline of his middle years, he would not have had the fortitude to endure the disappointments that his great work entailed. In the third stage, he was not just working but doing the work he felt made to do, not only surviving but living for a vital purpose. Yet he constantly faced the same essential challenges that had been presented to him throughout. All through his career fighting the extension of slavery, and all through his presidency, he faced painful fear and doubt—indeed, he faced it on an awful scale. But he repeatedly returned to a sense of purpose; from this purpose he put his head down to work at the mundane tasks of his job; and with his head down, he glanced up, often enough, at the chance to effect something meaningful and lasting. We justly look upon the transcendence of his final days with admiration, noticing the amazing balance between earthly works and self-dissolution.

Literature was a vital part of this process, helping Lincoln cope with his depression and draw important lessons from it. Shenk says that Lincoln

gave voice to his melancholy, reading, reciting, and composing poetry that dwelled on themes of death, despair, and human futility. These strategies offered him relief, sustenance, and a movement toward wisdom.

…Somewhat in the way that insulin allows diabetics to maintain their lives without eliminating the underlying problem, humor and poetry gave Lincoln succor without taking away his need for it. Rather than quash his conflicts, his therapies may actually have heightened them, for these were not medical strategies but moral and existential ones. Faced with questions about the meaning of life, Lincoln chose responses that engaged many of the same questions. Thus did “therapy” and “malady” come together in Lincoln’s journey toward wholeness.

Among the key authors were Lord Byron, Edgar Allan Poe, and Shakespeare. In Byron’s depression, Shenk writes, Lincoln recognized his own:

[Byron’s] verse play Manfred began with a soliloquy that instructed:

Sorrow is Knowledge: they who know the most

Must mourn the deepest o’er the fatal truth.

In Byron’s poem “The Dream,” a favorite of Lincoln’s, melancholy is described as “a fearful gift”:

What is it but the telescope of truth?

Which strips the distance of its fantasies,

And brings life near in utter nakedness,

Making cold reality too real!

Lincoln recognized his melancholy as well in “The Raven.” His friend John Stuart said that he “repeated it over and over”:

“He never read poetry as a thing of pleasure, except Shakespeare,” Stuart said. “He read Poe because it was gloomy.”

The raven in the poem is an emblem of Poe’s own melancholy. Sitting above the speaker’s determination to be rational (signified by the goddess Pallas Athena) is the prospect of a never-to-leave madness:

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o’er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted—nevermore!

According to Shenk, Lincoln was especially drawn to Shakespeare’s tragedies. Among his favorites, Lincoln listed King Lear, Richard III, Henry VIII, Hamlet, “and especially Macbeth. I think nothing equals Macbeth. It is wonderful.”

It makes sense that Lincoln would be drawn to Macbeth. Although he never engaged in Macbeth’s lawless behavior, like Macbeth he was ambitious and like Macbeth he saw himself forced to wade through blood to engage his objectives. Above all, he wrestled with Macbeth’s existential doubts. In his melancholy, one can imagine him resonating to

To know my deed, ’twere best not know myself.

And

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

Literature gave Lincoln a framework for understanding the full complexity of human beings. It kept him from being shallowly optimistic about human goodness, and it kept him from falling into despair over human perversity. Shakespearean wisdom is behind the memorable concluding image of Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address:

The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Lincoln knew, from reading the Bard, that angels and devils war within each and every one of us. He knew, from painful personal experience, how difficult it is to follow one’s better angels. Lincoln’s call is thrilling because he believes that we, as a nation, are up to the challenge.

One Trackback

[…] Lincoln Transformed Depression thru Lit […]