Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday

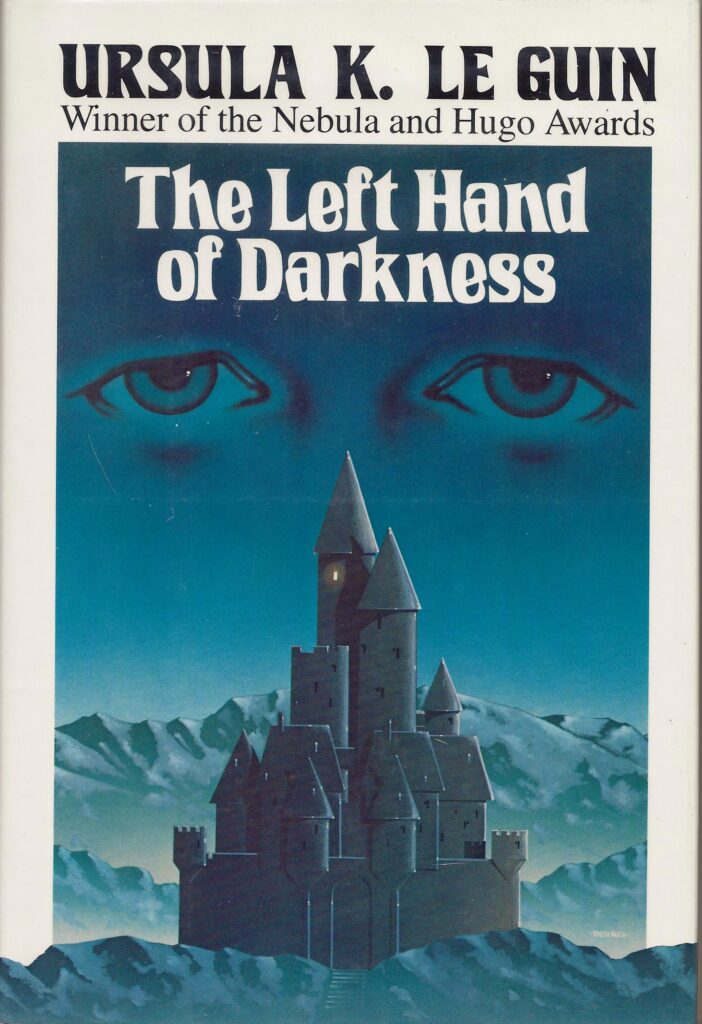

In my weekly series on Angus Fletcher’s book Wonderworks: The 25 Most Powerful Inventions in the History of Literature, I look today at his argument that Thomas More’s Utopia, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, and Ursula Le Guin’s Left Hand of Darkness help us to “decide wiser.” By this he means that these works help us see the world through expanded awareness by getting us to suspend judgment, thereby freeing ourselves from bias.

In what I am calling Fletcher’s anthropological-psychological approach to literature, the Ohio State “professor of story science” says that while staying comfortably inside one’s own judgments can feel “instantly good to our neurons”—it delivers “pleasant microdoses of emotional superiority”—in the long run doing so “make[s] us anxious, incurious, and less happy.” But we can improve our long-term mental well-being by suspending judgment:

The longer we suspend our judgments, the more accurate our subsequent verdicts become. This valuable fact has been uncovered by researchers who’ve spent decades probing the mechanics of better decision-making, only to discover the key is simply more time and more information. Which is to say: reserving our judgment until the last possible moment.

One of the best ways for suspending our judgments and expanding our view of the world is through traveling to other cultures—and if one can’t travel in actuality, one can travel through books. Thus Fletcher mentions such works as “Herodotus’s fourth century-BCE musings on Egyptian circumcision; Fan Chengda’s twelfth-century geographies of the painted towers of the southern Song dynasty; and Ibn Battuta’s fourteenth-century guides to the fruited rivers of Persia, the pickled pepper pods of Zanzibar, and the seed-eating wizards of the old Mughal Empire.”

The problem with travel books, however, is that, while we are invited to sample other cultures, the narrator is often, comfortably, one of us:

The travelogues of Herodotus, Fan Chengda, and Ibn Battuta are all told in the voice of a single author who presents himself as a trustworthy set of eyes; the sort of experienced guide whom we might hire on a real trip to show us around. This style of writing sets our brain on autopilot. Even when the travelogue introduces us to people who act unexpectedly, it supplies us with a constant source of social cues: the narrator.

Because this perspective is less jolting than actual physical travel, such travelogues are less effective at boosting our sense of wonder. Fletcher therefore turns to three works that find ways to jolt us further, with each one (he contends) being an advance over the previous.

The first is Thomas More’s Utopia, which has two narrators arguing over an imaginary land. In other words, there are two perspectives about how we are to judge it, that of the character Hythloday and that of “Thomas More.” Between these two perspectives, Fletcher says, we inhabit a “netural in-between suspended forever.”

Only, he adds, we don’t. While More has given us two narrators, his original readers “decided the Utopia had only one true author: Hythloday. The ‘Thomas More’ fellow, they reasoned, was a satirical gag, so they compressed Utopia’s unique two author structure into a traditional one-author travelogue.”

Swift in Gulliver’s Travels found a different way to jolt us, turning its narrator into an untrustworthy witness. By the end of the work, Gulliver has gone mad, so if we have been relying on him to give us a solid view of the world, we find ourselves suddenly having to readjust where we thought we stood. Otherwise, we would find ourselves putting trust in a man who agrees that human beings (the Yahoos) should be exterminated. Indeed, when the Platonic horses order him to leave their kingdom, he uses the skin of human babies for his ship’s sails and human fat to caulk the boat. When he returns home to his family, meanwhile, he faints at the smell of his wife and spends four hours a day talking to the horses in his stables.

But Fletcher, for reasons that I’ll disagree with in a moment, says that we find a way to become comfortable in Swift’s vision: we just see it as satiric, and with that familiar category settled, we are no longer jolted. Therefore, Fletcher says, we need one more Henry Jamesian turn of the screw (my comparison, not his). This, he says, we get from Ursula Le Guin’s Left Hand of Darkness.

In that sci-fi novel we have a character, Genly Ai, who is so revolted “at the ‘animals’ of his own species that he flees to escape them in a separate room.” But when he visits the family of a Gethen friend—another people—he finds himself “overwhelmed with ‘strangeness,’ feeling as shockingly repelled by the Gethens as he does by humans.” Fletcher writes,

With this narrative twist, Ursula Le Guin doubles the innovation of Gulliver’s Travels. It’s as though Gulliver ended by swooning in horror at his wife—then swooning in horror at the horses of his stables….So rather than allowing us to follow the readers of Gulliver’s Travels in rocketing out of the narrator’s orbit, Left Hand interrupts our thrust away, suspending us in a state of half repulsion and half agreement…Gently Ai is crazy—and he’s sane. He’s so strange—and he’s just like me…our judgment hung in space indefinitely.

Fletcher calls this “the invention of the Double Alien,” and it’s worth noting that this is not the only work where Le Guin uses it. In The Dispossessed, for instance, against the backdrop of an Earth that has been environmentally destroyed, the protagonist bounces back and forth between a capitalist planet where some lessons have been learned and its desolate moon, which has been settled by idealistic anarchists. Each society has its flaws, as the anarchist protagonist discovers as he finds himself out of step with both societies. As in Left Hand of Darkness, there’s resistance to any final judgment.

But I think the same occurs with Gulliver’s Travels, which I consider the world’s greatest work of satire. The extra twist, which Fletcher doesn’t mention, is how Swift satirizes satire itself. Swift never ever allows one to rest comfortably. Gulliver by the end of the book has essentially become a satirist—only horses are worth talking to he thinks—and Swift shows that to be a dead-end as well.

At the same time, he provides us with a character, the Portuguese sea captain who rescues Gulliver, who all but restores our faith in humanity. Even though Brits of the time associated the Portuguese with the Portuguese Inquisition, Pedro de Mendez goes out of his way to make sure that Gulliver gets safely home. It’s an example of something Swift once remarked in a letter, of loving people but hating humanity. Or to use his exact words,

I have ever hated all nations, professions, and communities, and all my love is toward individuals: for instance, I hate the tribe of lawyers, but I love Counsellor Such-a-one, and Judge Such-a-one: so with physicians—I will not speak of my own trade—soldiers, English, Scotch, French, and the rest. But principally I hate and detest that animal called man, although I heartily love John, Peter, Thomas, and so forth.

So one problem I find with Fletcher’s mind-expanding book is that he talks as though literary techniques are superseded just as human inventions are. But literature is more than a technique. Authors can create timeless works even while working within limitations. Swift doesn’t need Le Guin’s “double alien technique” to pull the rug out from under us every time we become complacent. He’s brilliant at always keeping us off balance.

Which is to say, in great works of art our judgment never finds a comfortable position upon which to rest.