Spiritual Sunday

On Friday I wrote that Wilkie Collins’s humorous depiction of a reader’s obsession with Robinson Crusoe could function as a parody of this blog. As house steward Gabriel Betteridge in The Moonstone sees it, Daniel Defoe’s novel is the key to better living. In his eyes, the book has all the answers to life’s questions.

Do you see me making the same claims for literature generally?

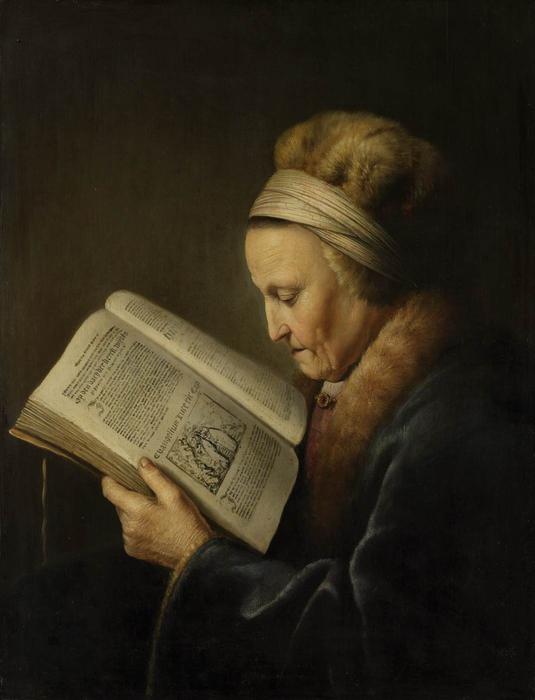

Upon further reflection, I realized that Gabriel Betteridge uses Robinson Crusoe as Crusoe himself uses the Bible. That, in turn, has led me to reflect the extent to which my own interactions with the Bible have influenced this blog. I share that with you today.

A number of years ago, I took—and then taught—the Episcopal Church’s four-year course Education for Ministry. Founded by the father of my best friend in middle school (Charlie Winters), EFM is designed for those who want to better understand the Bible. When I took the course, the first year was devoted to the Old Testament, the second to the New, the third to church history, and the fourth to theology.

The study is not altogether academic, however. In the course, the participants share personal stories that are surfaced by the Bible reading for that day. As a result, the Bible is transformed into a living guide that helps us grapple with the most pressing issues we face. The participants apply the methods used to unlock the Bible to unlocking a “slice of life” that one of them shares. The resulting realizations are sometimes profound.

As I was involved in the course, I realized that I could apply the same method to works of literature. I therefore adjusted my teaching (allowing, of course, for the different situations), with the result that my students began applying the literature we were reading to their lives. This blog owes its existence in part to Education for Ministry.

A couple of thoughts come to mind as I say this. One is that the practice of “close reading,” which literary study came to prize highly in the 20th century, itself has been traced back to Talmudic study of the Torah. In the 19th century, the study of literature—when it was studied at all—involved historical anecdotes, author biographies, and random associations. The belief that literature could offer up precious truths—that students could be initiated into its sacred mysteries if they were taught to examine texts in a disciplined manner—owes something to the influx of Jewish students into the universities.

These students were willing to study in a way that privileged young men with their “gentleman’s C’s” were not, and they began changing college culture. For a while, certain universities saw this as a problem and set up quotas limiting Jewish admission.

In the end, however, these students prevailed, academic “drudges” were no longer held in contempt, and colleges became more than social finishing schools. Many of our most prominent literary scholars have been Jewish, with Lionel Trilling, Stanley Fish, Stephen Greenblatt, Carolyn Heilbrun, Elaine Showalter, and Harold Bloom coming immediately to mind.

In short, that I related studying the Bible to studying literature is no accident.

I also think of how Victorian poet and critic Matthew Arnold saw literature as replacing religion in our increasingly secular society, given that both religion and literature command immense emotional and experiential power. If religion could no longer control the potentially rebellious working class, Arnold argued, perhaps literature could do the job.

When I was in my twenties and thirties, I myself didn’t see the point of religion. After all, as I told the rector of our local church, I had the rich symbolic language of literature. I no longer think this, and each plays a vital role in my life

But if I sometimes sound evangelical as I advocate for literature—well, you’re not just imagining things.