Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. I’ll subscribe you via Mailchimp for the weekly or email you directly for the daily (your choice). Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone.

Wednesday

My friend Dennis Johnson recently alerted me to a powerful commencement address, delivered by the accomplished novelist Nicole Krauss and published in the Washington Post. Author of The History of Love and The Great House, both of which I highly recommend, Krauss argues that literature is essential if humans are to step into freedom and live up to our potential.

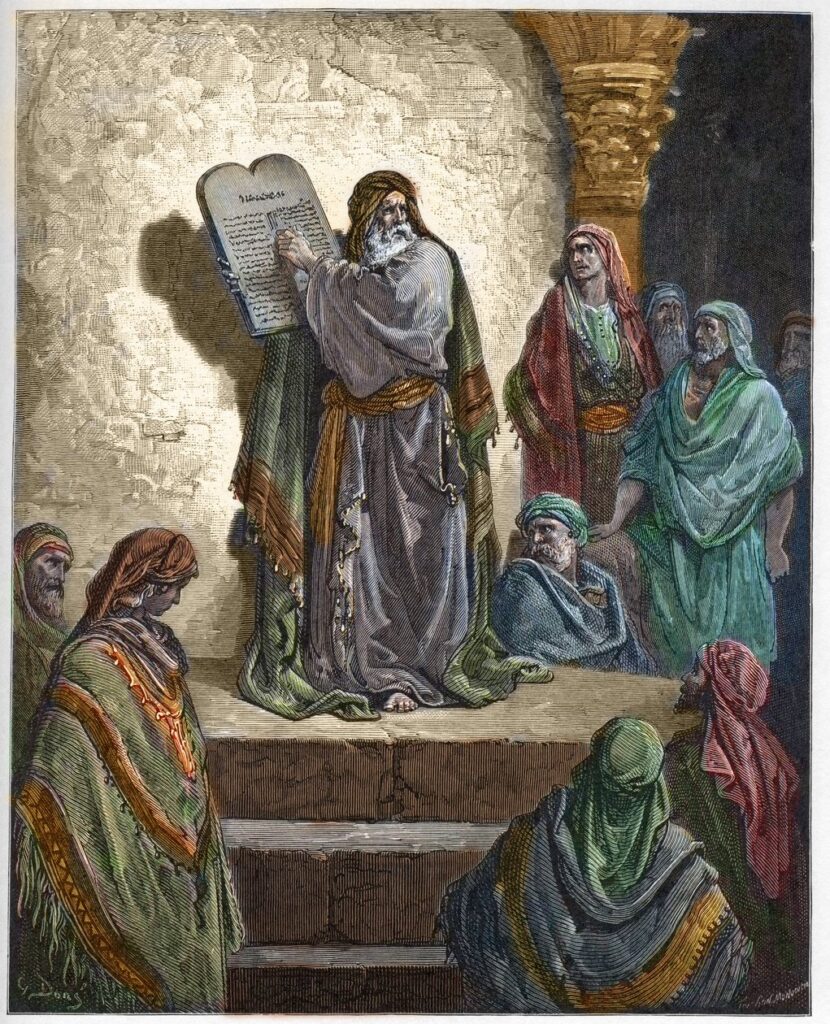

Krauss grounds her case in a powerful historical moment. When the Jews were captives in Babylon, they had turned to writing and transcribing the Torah because they had no access to their land or their Temple. Upon their return to Jerusalem, the question was whether they were going to be a people of the Temple or a people of the Torah. Krauss describes what happened next:

[I]t is in Nehemiah that we read of something truly extraordinary: the first record of the Torah being read in public. Ezra brought the scroll out and read from it, “facing the square before the Water Gate, from the first light until midday, to the men and the women and those who could understand; the ears of all the people were given to the scroll of the Torah. … They read from [it], translating it and giving the sense; so they understood the reading.”

Krauss says that “it is impossible to exaggerate how momentous this moment was”:

At perhaps the greatest juncture the Jews have ever faced, the Temple was replaced by Torah. Sacrifice was replaced by reading, teaching and study. And Judaism was made independent of place and became portable, ensuring its survival to this day.

Not only did Judaism become portable but the first steps towards democratization had been taken. As Krauss explains it,

In those few lines of Nehemiah, we find a rejection of a hierarchical system based on hereditary power in the hands of the few, toward the town square, where all men and women are offered the chance to participate, to listen, learn and understand the teachings for themselves. It might be argued that from that day on, all that is required to live as a Jew are words. No more, and no less.

This is where the importance of writing comes in. Krauss says that she writes, just as she reads, because she believes that

in the realm of literature we are, each of us, free. Free to imagine, to invent, to change our minds, to travel through time, across space, to feel and experience the full breadth of ourselves, and to do what I don’t believe can be done in any other realm, medium or dimension: to step into the mind of another. Feel what it is to live inside another and, in the process, enlarge ourselves beyond the borders of selfhood, into the vaster fields of mutual understanding and empathy.

To intrude into Krauss’s argument for a moment, in my book Better Living through Literature I make the case that the 19th century Romantic Imagination expanded the franchise in a similar way. When a poet like Wordsworth began to make shepherds, leech gatherers, and wheat gatherers the subjects of his verse, he opened the door for poets and writers

to use the Imagination to step beyond their own narrow class boundaries in ways that would have been, well, unimaginable in earlier times. Through literature authors have entered the lives of the marginalized (Walt Whitman), the urban poor (Charles Dickens), American slaves (Harriet Beecher Stowe), Dorset dairy maids (Thomas Hardy), French coalminers (Emile Zola), Nebraska pioneers (Willa Cather), Harlem residents (Langston Hughes), African American sharecroppers (Jean Toomer), African American homosexuals (James Baldwin), bankrupted Oklahoma farmers (John Steinbeck), Laguna Pueblo war veterans (Leslie Marmon Silko), transplanted Pakistanis (Hanif Kureishi), West Indian immigrants (Zadie Smith), American lesbians (Alison Bechdel), and on and on….[T]he Romantic Imagination elevated lower-class figures to new levels of importance. In the process, it inspired generations of social and political idealists and changed conversations about public policy.

Krauss, however, adds one major caveat to her argument that literature is “fundamentally democratic.” “To access its freedoms,” she writes, “we must be taught to read, value and engage with literature.” She sees us standing at a crossroads where the future of reading, writing, and literature is at stake, along with “all of the expansive freedom they have afforded us.”

Concerned about AI and “the demolition of the capacity to read and engage with a book,” she worries that we

have lost not just our ability to concentrate on deciphering long passages of written language; we have, I believe, begun to lose our attachments to the meaning of words and sentences, which we once trusted to carry the precious freight of communicating who we are — to ourselves and to each other. The blatantly, proudly senseless speech of our current leaders is not the cause, it is merely the most extravagant example of what happens when an entire culture — increasingly, the monoculture of the world — gives up on, and ceases to be capable of, the struggle to funnel meaning into language — to translate themselves, their thoughts, and their ideas into words that others can read and share.

Writing and reading take effort, she points out, and without that effort “we will slide deeper and deeper into inchoateness, darkness, violence, diminished freedom for all and a diminished state of human being.”

She takes heart, however, from all the professors who make it their life work to ensure that their students “have access to the freedom that comes with becoming a reader, being able to write for oneself, and partake in a culture of literature and ideas.” (Remember, this is a commencement address.) She also takes the long view, noting that, after all, we have been finding words for ourselves and have been writing our own story for thousands of years. In the process, we “have done something far more radical than expressed ourselves: We have invented ourselves. We have asked the essential question: Who are we, and what kind of people do we want to be?”

“Where there is destruction,” she concludes, “there is also the potential for tikkun, for repair.” To rise to the occasion, however, we must be educated “in the bonding of language and meaning.”

Authors, teachers, librarians, parents, bloggers, social workers, therapists, friends, and others are critical to making this educational bonding happen.