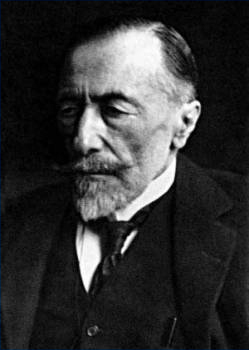

Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad

I have just begun reading a book that is very much in tune with this website: Joseph L. Badaracco’s Questions of Character: Illuminating the Heart of Leadership through Literature, published by Harvard Business School Press (2006). I report here on the introduction.

The author talks about assigning Joseph Conrad’s “Secret Sharer” to a group of businessmen in a leadership workshop. The story, which I first encountered in a “Jungian Approaches to Literature” course, is about a ship’s captain who allows a mysterious stranger on board his ship. The captain hides him there and then, a few days later, sails close to shore to the man can swim ashore.

At first, Badaracco says, the captain gets criticized by members of the workshop for being so irresponsibile. Then, however, a “highly respected CEO” in the group looks around and says, “I’ll bet most of you have done similar things, and you wouldn’t be here today if you hadn’t.” At that point things take off. Badaracco reports:

I spent the rest of the session listening to a discussion, rather than leading it. The conversation covered many important questions. Was the new captain ready to take on his responsibilities? What did his actions reveals about his character? How do leaders learn from their mistakes? The group was deeply engaged, arguing about the captain and talking about their own experiences In fact, about a year later, a colleague of mine ran into someone who had attended the discussion, and she wanted to continue talking about the captain.”

Badaracco asserts that literature is critical in leadersip training, in part because, in real life, “most people see the leaders of their organizations only occasionally and get only fleeting glimpses of what these leaders are thiking and feeling.” Serious literature, on the other hand, “offers a view from the inside.” The author goes on to say that literature

“opens doors to a world rarely seen—except, on occasion, by leaders’ spouses and closest friends. It lets us watch leaders as they think, worry, hope, hesitate, commit, exult, regret, and reflect. We see their characters tested, reshaped, strengthened, or weakened. These books draw us into leaders’ worlds, put us in their shoes, and at times let us share their experiences.”

The chapters in the book are as follows:

–Do I Have a Good Dream? – Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman

–How Flexible Is My Moral Code? – Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart

–Are My Role Models Unsettling? – Allen Gurganus’s “Blessed Assurance”

–Do I Really Care? – F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Love of the Last Tycoon

–Am I Ready to Take Responsibility? – Conrad’s “Secret Sharer”

–Can I Resist the Flow of Success? – Louis Auchincloss’s I Come as a Thief

–How Well Do I combine Principles and Pragmatism? – Robert Bolt’s Man for All Seasons

–What Is Sound Reflection? – Sophocles’ Antigone

–Judging Character

The author acknowledges that literature is not enough and that one also needs the perspectives that comes from “historians, journlalists, scholars, leaders’ personal accounts of their experiences, and our own observations.” And of course, one also needs hands-on experience. But personal experience, he notes, is “narrow and skewed—in a world with six billion people and thousands of years of recorded history, each of us is only a tiny, fleeting dot of consciousness.” Literature’s advantage is that it is often focused on character—certainly fiction is—and Badaracco sees questions of character as crucial to successful leadership. Leaders must know who they really are and even the best ones can lose their way. Literature can help on both counts

As I dip into the book, I’ll periodically report on different chapters. For now, I’m just pleased to find another books that confirms that literature provides us with vital life skills.