Thursday

The Guardian newspaper recently had an article on “the top single mothers in fiction,” which is my kind of article. Sadly, only the top three are from classic fiction (which partly explains why they’re the only ones I recognized), so I set myself the challenge to see if I could come up with another seven. Here’s my list. Please send in your favorites.

I love the Guardian’s top three, with the choice of Euripides’s Medea particularly inspired. Here’s what author Beth Morrey has to say about her:

Medea

“It might seem odd to start with a drama about a barbarian witch who kills her own children when her husband leaves her for a princess. But shoutout to Euripides for featuring a female protagonist who dominates the action, a chorus of Corinthian women, and a scot-free exit. Medea murders her sons in cold blood to annoy her ex, Jason. But Jason is maddening – a shameless social climber who rubs salt in the wound by suggesting Medea stay on as a mere mistress. Medea has the last laugh, escaping with the bodies of their sons in Helios’ chariot, hinting the Gods are on her side. This is a woman scorned taking back control and getting away with it. The Athenian audience didn’t react favorably to the notion, awarding the play third place (out of three) at the Dionysia festival of 431 BCE. I’m sure Euripides would be heartened to know Medea’s No 1 in my top 10.” [Beth Morrey]

Mrs. Dashwood

I heartily approve of Morrey’s selection of Elinor and Marianne’s mother in Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility. Mrs. Dashwood all but reverts to her teen years after her husband dies, relegating head of the family duties to eldest daughter Elinor. As a result, she doesn’t exercise motherly caution when Marianne falls in love with Willoughby, which almost ends in disaster. A great moment is when, late in the book, she realizes that heartbroken Elinor needs her to be a mother.

Marmee

Morrey includes Margaret (Marmee) March in her list because her husband is absent, elevating her to head of the household. Morrey describes Little Woman’s matriarch as “the archetypal single mother saint” and describes her as “infuriatingly perfect.” She adds, however, that

Alcott hints at dark depths when Marmee confesses she was once as hot-headed as her daughter Jo, but learned to control her temper. I would love to have seen a tiny flare of it, the glimmer of original sin.

Hester Prynne

I don’t know how Morrey could have left the protagonist of The Scarlet Letter off her list, but so she has. The mother of Pearl eventually arises to sainthood herself but at one point thinks that she can just throw away her scarlet letter and live free of the taint. (Pearl lets her know otherwise.)

Helen Graham

Another character who must be included on every such list is the inhabitant of Anne Bronte’s Wildfell Hall, who flees there with her son to save him from his abusive and alcoholic father. She is accused by villagers who don’t know her story of overprotecting her son, but she knows what’s at stake and risks social shunning to keep him safe. Tenant of Wildfell Hall ranks right up there with Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights.

The Countess of Roussillon

This is the mother-in-law every woman should dream of. The mother of the irresponsible Bertram in Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well, the countess takes Helena’s side when Bertram proves a brute. I saw Judi Densch play her in a Stratford-upon-Avon production and will never forget the scene where she lets Bertram have it for abusing his wife. Dench did no more that make a tiny dismissal gesture with her right hand, but I was thrown back in my seat by the move. That’s the moment when I realized Dench’s greatness.

Clara Copperfield and then adoptive mother Betsey Trotwood

Widowed Clara may be angelic—one of Dickens’s child women—but she’s an incompetent mother, with her worst action being marrying the abusive Murdstone when David is seven. After being sent away to an awful school and then an awful job, David is fortunate (after running away) to be taken in by Betsey Trotwood, recently named by my English professor son as Dickens’s greatest creation. Toby Wilson-Bates quotes David Copperfield’s opening lines before declaring Trotwood the winner of his contest:

“Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.” The pages show you lost, son. From donkeys to dandies, Betsey takes and vanquishes all comers.

Taylor Greer

Barbara Kingsolver exploded on the literary scene with her sassy, foul-mouthed protagonist in The Bean Trees. Greer is given and unofficially adopts an Indian baby, after which Kingsolver had to write a sequel (Pigs in Heaven) to clean up some of the mess she had gotten into with her story. (A white woman can’t just take and raise an Indian baby, even if it is given to her, without the author addressing the various ethical and cultural issues that arise—which Kingsolver then does in Pigs in Heaven.)

Lulu Nanapush Lamartine

One of Louise Erdrich’s great creations, Lulu is rescued from a reservation school by village elder Nanapush (in Tracks), who raises her as his own and tells her stories about her extraordinary mother Fleur. Lulu goes on to have her own colorful life, birthing nine children (eight of them sons) to five different fathers—and while members of the tribe try to shame her, she always walks with her head high. As she explains at one point in the Pulitzer Prize-winning Love Medicine,

When they tell you that I was heartless, a shameless man-chaser, don’t ever forget this: I loved what I saw. And yes, it is true that I’ve done all the things they say. That’s not what gets them. What aggravates them is I’ve never shed one solitary tear. I’m not sorry. That’s unnatural. As we all know, a woman is supposed to cry.

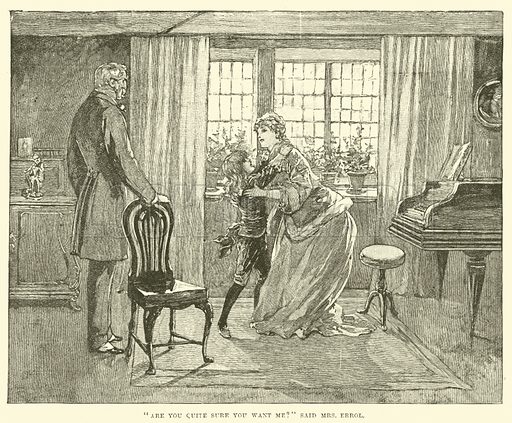

Mrs. Cedric Errol

This last character few will recognize outside myself, but the mother of Little Lord Fauntleroy was an important part of my childhood. In Frances Hodgson Burnett’s 1886 novel, Fauntleroy’s father, the son of an earl, has married this American woman, been disinherited as a result, and then died, leaving her alone with her angelic son. When the death of the earl’s older sons leaves Fauntleroy as the next heir, mother and child return to England, but the harsh and unforgiving earl refuses to see her, even though he is won over by Fauntleroy. In the end, of course, he learns to appreciate the woman his son risked everything to marry.

My girl side was in love with Fauntleroy when I was young, especially his long locks, his velvet suits and his lace collars. I was later to learn that there was a Fauntleroy craze for a while, with mothers dressing their sons up in this fashion. While many boys hated it, my father loved his mother outfitting him this way. (This would have been forty years after the book appeared but Granny, born the year the book appeared, was very Victorian.) Rereading Burnett’s novel now is like eating one of those sugary treats we loved as children but find inedible as adults. For an example, here’s a passage highlighting one of the consolations of single motherhood:

So when he knew his papa would come back no more, and saw how very sad his mamma was, there gradually came into his kind little heart the thought that he must do what he could to make her happy. He was not much more than a baby, but that thought was in his mind whenever he climbed upon her knee and kissed her and put his curly head on her neck, and when he brought his toys and picture-books to show her, and when he curled up quietly by her side as she used to lie on the sofa. He was not old enough to know of anything else to do, so he did what he could, and was more of a comfort to her than he could have understood….

As he grew older, he had a great many quaint little ways which amused and interested people greatly. He was so much of a companion for his mother that she scarcely cared for any other. They used to walk together and talk together and play together. When he was quite a little fellow, he learned to read; and after that he used to lie on the hearth-rug, in the evening, and read aloud—sometimes stories, and sometimes big books such as older people read, and sometimes even the newspaper; and often at such times Mary, in the kitchen, would hear Mrs. Errol laughing with delight at the quaint things he said.

So that’s my list. Some of the mothers are angelic, some supremely confident, some murderous killers. Expect a post on single fathers in the near future.

Further thought: A slighting reference to Fauntleroy shows up in the Eugene Field poem “Just afore Christmas”:

Father calls me William, sister calls me Will,

Mother calls me Willie, but the fellers call me Bill!

Mighty glad I ain’t a girl – ruther be a boy,

Without them sashes, curls, an’ things that’s worn by Fauntleroy!

Love to chawnk green apples an’ go swimmin’ in the lake –

Hate to take the castor-ile they give for belly-ache!

‘Most all the time, the whole year round, there ain’t no flies on me,

But jest ‘fore Christmas I’m as good as I kin be!