Tuesday

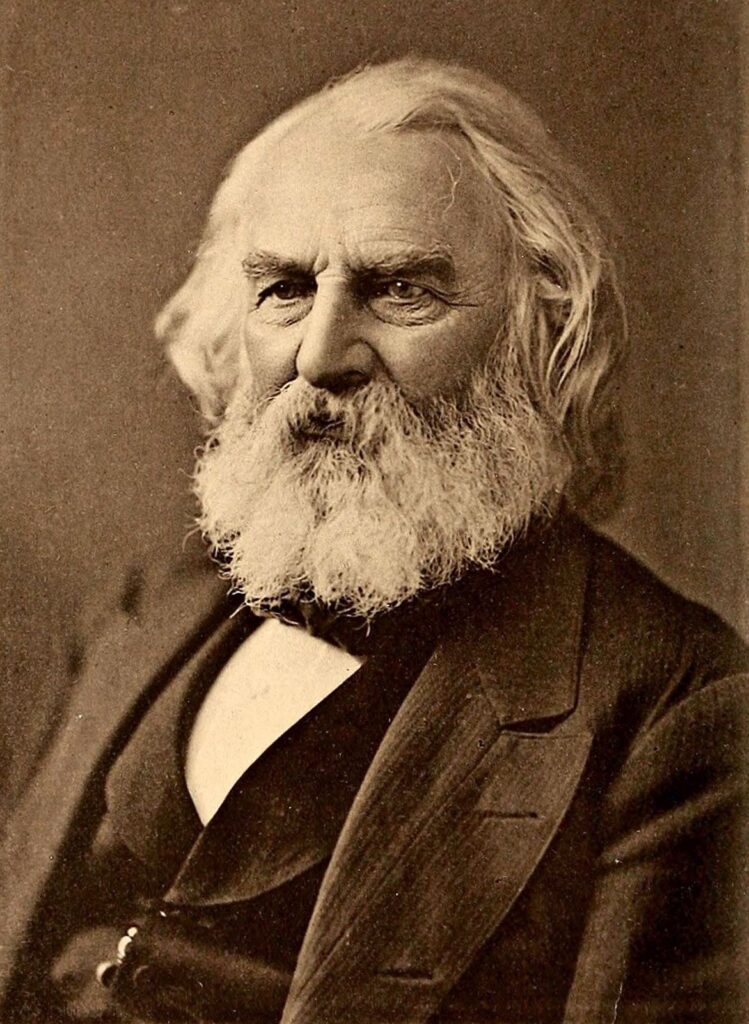

I wrote last week of Matthew Pearl’s The Dante Club (2003), a literary murder mystery starring poets Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, and their publisher J.T. Fields. Pearl plays with these legendary figures as a child plays with dolls or toy soldiers imagining them interacting and conversing as they work on a controversial translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

I wrote in my earlier post about how Pearl thinks America would have responded to Dante in the year 1867. Today I share some of his other observations of literature’s impact.

For instance, he has Ralph Waldo Emerson show up and speak slightingly of Longfellow’s poetry:

Emerson straightened the papers had had brought to Fields in order to show that the purpose of his visit was completed. “Remember that only when past genius is transmitted into a present power shall we meet the first truly American poet. And somewhere, born to the streets rather than the athenaeum, we will come upon the first true reader. The spirit of the American is suspected to be told, imitative, tame—the scholar decent, indolent, complaisant. The mind of our country, taught to aim at low objects, eats upon itself. Without action, the scholar is not yet man. Ideas must work through the bones and arms of good men or they are no better than dreams. When I read Longfellow, I feel utterly at ease—I am safe. This shall not yield us our future.

The man that Emerson in fact believed was “the first truly American poet” is mentioned by publisher Fields in a conversation with a junior partner:

“Do you know, Osgood why we did not publish Whitman when he brought us his Leaves of Grass?” He did not wait for a reply. “Because Bill Ticknor did not want to call down touble on the house over the carnal passages.”

“May I ask whether you regret that, Mr. Fields?”

He was pleased with the question. His tone modulated from employer’s to mentor’s. “No I don’t, my dear Osgood. Whitman belongs to New York, as did Poe.” That name he said more bitterly, for reasons that still smoldered. “And I’ll let them keep what few they have. But from true literature we mustn’t ever cower, not in Boston. And shall not now.”

Fields’s animus against Poe is never explained. (Maybe he explains it in his 2006 novel, The Poe Shadow.) It’s worth noting, however, that not everyone shares Emerson’s dismissal of Longfellow. In fact, he is seen as a rock star. One woman, in awe of him when he shows up in her house looking for the murderer, explains what a boon he is to her life. She explains he also soothes her husband, who is suffering from Civil War PTSD and whom she recites Longfellow’s Evangeline to at night:

She tried her best to explain her wonderment [at Longfellow’s appearance]: explained how she read Longfellow’s poetry before going to sleep each night: how when her husband was bedridden from the war she would recite Evangeline aloud to him; and how the gently palpitating rhythms, the legend of faithful but uncompleted love, would soothe him even in his sleep—even now sometimes, she said sadly. She knew every word of “A Psalm of Life,” and had taught her husband to read it as well; and whenever he left home, those verses were her only release from fear.”

I had to look up “A Psalm of Life.” Longfellow explains that it is “what the heart of the young man said to the psalmist”:

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.Life is real! Life is earnest!

And the grave is not its goal;

Dust thou art, to dust returnest,

Was not spoken of the soul.Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destined end or way;

But to act, that each to-morrow

Find us farther than to-day.

Evangeline, meanwhile, opens with:

This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks,

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.

Loud from its rocky caverns, the deep-voiced neighboring ocean

Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the forest.

One other Longfellow note. We encounter the poet’s daughters, whose names I grew up knowing from having read “The Children’s Hour”: “Grave Alice, and laughing Allegra, and Edith with golden hair.” It is to Edith that the poet, whenever he is feeling tender, recites the final stanza of his poem “Children”:

Ye are better than all the ballads

That ever were sung or said;

For ye are living poems,

And all the rest are dead.

In short, Pearl has written a novel in which he can imagine poetry playing a far more prominent role in people’s lives than it does today.