Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Sunday

As I’ve immersed myself in Victorian novels recently, I’ve been struck by how religious many of them are. To be sure, not all novelists talk about God—Emily Bronte, Charles Dickens, and Wilkie Collins barely do so, for instance—but there are others for whom faith is a central theme. I particularly think of Charlotte Bronte, Elizabeth Gaskell, and (today’s subject) George MacDonald.

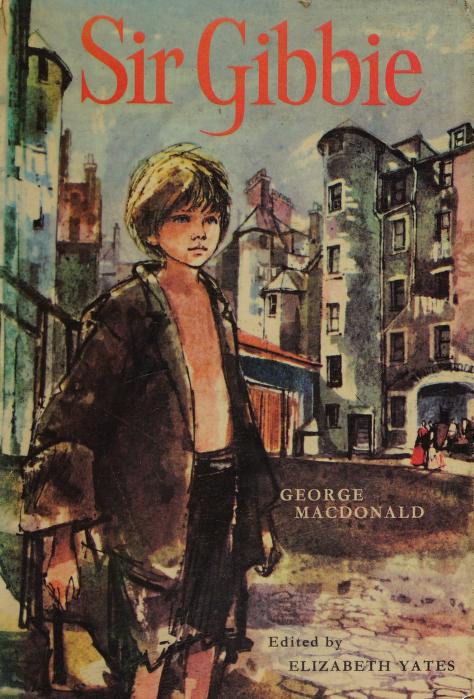

While I loved MacDonald’s Princess and the Goblin and Princess and Curdie when I was a child, I wonder what I would have thought of MacDonald’s more religious Sir Gibbie, which I missed reading only because my father had mistakenly filed it in the adult section of our family library. In any event, I read it this past year after my friend Lani Irwin mentioned it and loved his Christian vision.

In fact, it sent me to the internet, where I learned that MacDonald, at one point a Congregationalist minister, was essentially fired by his flock for not being judgmental enough. Refusing to ascribe to the Calvinist tenet that only the elect will be saved, MacDonald believed that true repentance is attainable by all. According to his biographer William Raeper, whose views are summed up in Macdonald’s Wikipedia entry, MacDonald “celebrated the rediscovery of God as Father, and sought to encourage an intuitive response to God and Christ through quickening his readers’ spirits in their reading of the Bible and their perception of nature.”

One could add that MacDonald, perhaps the preeminent Victorian fairytale author, used his children’s literature to quicken those spirits–although as he saw it, “I write, not for children, but for the child-like, whether they be of five, or fifty, or seventy-five.”

In MacDonald’s view, Christ came to earth to help us deal with “the disease of cosmic evil.” MacDonald’s God is not an angry deity seeking to punish us for our sins but a loving one who wishes all of us to discover the love within. As MacDonald rhetorically put it, did Jesus “not foil and slay evil by letting all the waves and billows of its horrid sea break upon him, go over him, and die without rebound—spend their rage, fall defeated, and cease?” In so doing, Jesus cleared the way for us to become “at one” with God.

One sees the process at work in Sir Gibbie, which is the story of a boy, born mute and in poverty, who discovers that he is of Scottish nobility. Rather than let this go to his head, however, he follows his generous spirit, which may be shielded from fallen society in part by his handicap. He is a natural Christian before encountering the Bible, and when he learns about Jesus, he finds in him a kindred spirit.

At an early age, Gibbie is orphaned in a large city, from which he flees after a friend is murdered. Finding himself in the Scottish mountains, he hears Bible stories from the poor farmers who provide refuge after he is cruelly beaten. MacDonald makes clear that the father who reads the scripture each night gets closer to the essence of the faith than do more theologically sophisticated Christians:

Now he was not a very good reader, and, what with blindness and spectacles, and poor light, would sometimes lose his place. But it never troubled him, for he always knew the sense of what was coming, and being no idolater of the letter, used the word that first suggested itself, and so recovered his place without pausing. It reminded his sons and daughters of the time when he used to tell them Bible stories as they crowded about his knees; and sounding therefore merely like the substitution of a more familiar word to assist their comprehension, woke no surprise. And even now, the word supplied, being in the vernacular, was rather to the benefit than the disadvantage of his hearers. The word of Christ is spirit and life, and where the heart is aglow, the tongue will follow that spirit and life fearlessly, and will not err.

The mother of the household, meanwhile, bypasses theology and talks about Jesus in a way that comes from the heart:

So, teaching him only that which she loved, not that which she had been taught, Janet read to Gibbie of Jesus, talked to him of Jesus, dreamed to him about Jesus; until at length—Gibbie did not think to watch, and knew nothing of the process by which it came about—his whole soul was full of the man, of his doings, of his words, of his thoughts, of his life. Jesus Christ was in him—he was possessed by him. Almost before he knew, he was trying to fashion his life after that of his Master.

About which MacDonald comments,

Should it be any wonder, if Christ be indeed the natural Lord of every man, woman, and child, that a simple, capable nature, laying itself entirely open to him and his influences, should understand him?

“Doing the will of God leaves me no time for disputing about His plans,” MacDonald writes elsewhere, and Janet lives her own life this way:

Being in the light she understood the light, and had no need of system, either true or false, to explain it to her. She lived by the word proceeding out of the mouth of God. When life begins to speculate upon itself, I suspect it has begun to die. And seldom has there been a fitter soul, one clearer from evil, from folly, from human device—a purer cistern for such water of life as rose in the heart of Janet Grant to pour itself into, than the soul of Sir Gibbie. But I must not call any true soul a cistern: wherever the water of life is received, it sinks and softens and hollows, until it reaches, far down, the springs of life there also, that come straight from the eternal hills, and thenceforth there is in that soul a well of water springing up into everlasting life.

Serving the family as shepherd, Gibbie finds the solitude of the mountains conducive to his spiritual growth. Love of nature becomes a pathway to God:

[A]s the weeks of solitude and love and thought and obedience glided by, the reality of Christ grew upon him, till he saw the very rocks and heather and the faces of the sheep like him, and felt his presence everywhere, and ever coming nearer.

Eventually Gibbie’s parentage is discovered and he is taken back to the city, where he lives with the Anglican rector who tracked him down. This leads to various satiric episodes, including one where he comes upon the man and his wife quarreling. His response first irritates but then shames them:

A discreet, socially wise boy would have left the room, but how could Gibbie abandon his friends to the fiery darts of the wicked one! He ran to the side-table before mentioned. With a vague presentiment of what was coming, Mrs. Sclater, feeling rather than seeing him move across the room like a shadow, sat in dread expectation; and presently her fear arrived, in the shape of a large New Testament, and a face of loving sadness, and keen discomfort, such as she had never before seen Gibbie wear. He held out the book to her, pointing with a finger to the words—she could not refuse to let her eyes fall upon them—“Have salt in yourselves, and have peace one with another.”

This is far from Gibbie’s only social faux pas. He insists on mingling with the lower-class urban dwellers, sometimes (with thoughts of Jesus and the tax collector in his mind) bringing them to the Sclater dinner table. He also, much to their horror, makes friends with fallen women.

If, in Ivan Karamazov’s mind (I’m thinking of Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor parable), the world would reject Christ if he were to come again, in MacDonald’s story the Christ-like Gibbie transforms the world. When he ultimately becomes lord of his Scottish estate, he turns it into a refuge

of all that were in honest distress, the salvation of all in themselves such as could be helped, and a covert for the night to all the houseless, of whatever sort, except those drunk at the time. Caution had to be exercised, and judgment used; the caution was tender and the judgment stern. The next year they built a house in a sheltered spot on Glashgar, and thither from the city they brought many invalids, to spend the summer months under the care of Janet and her daughter Robina, whereby not a few were restored sufficiently to earn their bread for a time thereafter.

C.S. Lewis, who owes a huge fantasy debt to MacDonald–one sees the influence throughout the Narnia books–says that his sermons were just as influential:

I know hardly any other writer who seems to be closer, or more continually close, to the Spirit of Christ Himself. Hence his Christ-like union of tenderness and severity. Nowhere else outside the New Testament have I found terror and comfort so intertwined. …

G.K. Chesterton, meanwhile, has noted that “only a man who had ‘escaped’ Calvinism could say that God is easy to please and hard to satisfy.”

Last Sunday I wrote about how Anglicans engage in theology, not systematically, but through literature. Though not an Anglican—in fact, he had theological battles with his Congregationalist congregation—MacDonald does use his literature to sort through his Christianity. While some will find his novel preachy—and perhaps I would have had I encountered it earlier—I now find myself buoyed by his vision.

Further note: I find fascinating Wikipedia’s list of authors who have been influenced by MacDonald, from Lewis Carroll—MacDonald apparently persuaded him to publish Alice in Wonderland—to Madeleine L’Engle and Neil Gaiman. Here’s the list:

W.H. Auden, David Lindsay, J.M. Barrie, Lord Dunsany, Elizabeth Yates, Oswald Chambers, Mark Twain, Hope Mirrlees, Robert E. Howard, L. Frank Baum, T.H. White, Richard Adams, Lloyd Alexander, Hilaire Belloc, G.K. Chesterton, Robert Hugh Benson, Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, Fulton Sheen, Flannery O’Connor, Louis Pasteur, Simone Weil, Charles Maurras, Jacques Maritain, George Orwell, Aldous Huxley, Ray Bradbury, C.H. Douglas, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Walter de la Mare, E Nesbit, Peter S. Beagle, Elizabeth Goudge, Brian Jacques, M.I. McAllister, Madeleine L’Engle and Neil Gaiman.