Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. I’ll subscribe you via Mailchimp for the weekly or email you directly for the daily (your choice). Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone.

Thursday

One of the most baffling aspects of Trump cultism for me is his enduring support amongst white fundamentalists. Don’t these people, who want to plaster the Ten Commandments on every classroom and government office wall, realize that they have pledged their fealty to someone who all his life has routinely broken every one of those commandments (well, except for murder)? Doesn’t hypocrisy mean anything to these people? Or does their fervent approval of Trump’s racism and sexism blind them to what is obvious to everyone else.

I ask the same question of those who, every two years, send my Tennessee Congressman back to Washington. Scott DesJarlais, who once was unofficially named the worst member of Congress before the competition for that honor became so stiff, is an ardent pro-life family values guy who was revealed to have urged abortions for both his ex-wife and his mistress. Yet none of this seems to matter in my heavily Christian district.

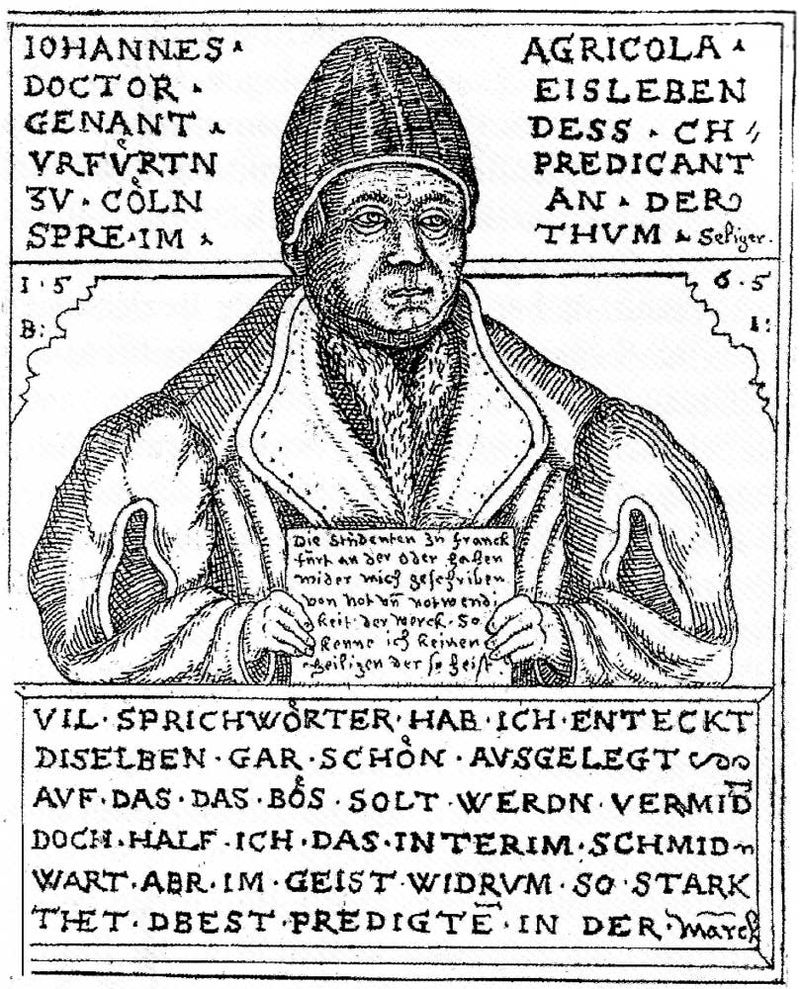

I have gained some enlightenment into this recently from a Robert Browning poem about an antinomian figure from the 16th century, leading me to wonder if there’s an antinomian strain in Trumpist Christianity. “Johannes Agricola in Meditation” is a dramatic monologue in which the speaker ponders his position in the universe.

If you don’t know what an antinomian is, you’re not alone. I only learned recently, thanks to a session with my faculty reading group where we discussed the poem, that it’s an extreme form Calvinism–with Calvinism itself providing much of the foundation of Protestant fundamentalism. As defined by Wikipedia, an antinomian

is one who takes the principle of salvation by faith and divine grace to the point of asserting that the saved are not bound to follow the moral law contained in the Ten Commandments. Christian antinomians believe that faith alone guarantees humans’ eternal security in Heaven regardless of one’s actions.

The antimonians’ faith is not only in God but in their own election by God. In the Calvinist doctrine of predestination, only God’s grace, not our good works, determines whether we go to heaven or hell. One logical extension of this is that it doesn’t matter if one sins. Or as Agricola once stated, “If you sin, be happy, it should have no consequence.” One can see how this could stem from the Calvinist view, “Once saved, always saved.”

So I’m thinking that those Christian Trumpists who believe that he has been ordained by God—and there are many of them—have no problem with giving him an automatic sin pass. Forget about Jesus’s “Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers of mine, you did for me.” That particular standard does not apply.

Browning is best known for his dramatic monologues in which the speakers inadvertently reveal their inner character as they talk about this or that. “My Last Duchess” is often taught in classrooms because students have a chance to play detective and, reading between the lines, figure out what has happened to the duke’s former wife. (Spoiler alert: He murdered her.) “Agricola in Meditation” begins with the speaker declaring that, when he looks up at the heavens, he doesn’t pay attention to the “dazzling glory” of the sun, moon and starts. That’s because, as one of the elect, he intends to bypass them and go straight to God. He is, in other words, “splendor-proof”:

There’s heaven above, and night by night

I look right through its gorgeous roof;

No suns and moons though e’er so bright

Avail to stop me; splendor-proof

I keep the broods of stars aloof:

For I intend to get to God,

For ‘t is to God I speed so fast,

For in God’s breast, my own abode,

Those shoals of dazzling glory, passed,

I lay my spirit down at last.

Because God has predestined us from before we were born—indeed, before He “piled the heavens” and “fashioned star or sun”—Agricola is sure he has nothing to worry about:

I lie where I have always lain,

God smiles as he has always smiled;

Ere suns and moons could wax and wane,

Ere stars were thundergirt, or piled

The heavens, God thought on me his child;

Ordained a life for me, arrayed

Its circumstances every one

To the minutest; ay, God said

This head this hand should rest upon

Thus, ere he fashioned star or sun.

Indeed, God has made Agricola as a tree that is destined to flourish. And like a tree, he will be “guiltless forever”:

And having thus created me,

Thus rooted me, he bade me grow,

Guiltless forever, like a tree

That buds and blooms, nor seeks to know

The law by which it prospers so:

But sure that thought and word and deed

All go to swell his love for me,

Me, made because that love had need

Of something irreversibly

Pledged solely its content to be.

Even if this tree were to be watered with poison—in other words, if it were to sin—there’s no problem. Agricola assures himself that the poison would be converted into “blossoming gladness”:

Yes, yes, a tree which must ascend,

No poison-gourd foredoomed to stoop!

I have God’s warrant, could I blend

All hideous sins, as in a cup,

To drink the mingled venoms up;

Secure my nature will convert

The draught to blossoming gladness fast:

Such is not the case, unfortunately, for those foredoomed to be gourds rather than trees. Even good water won’t help them:

While sweet dews turn to the gourd’s hurt,

And bloat, and while they bloat it, blast,

As from the first its lot was cast.

Browning’s poem doesn’t only help us understand how antinomians and their American descendants get a pass when it comes to sinning. It also gives us insight into the delight they appear to take when innocents are grabbed off the streets and carted off to Salvadoran or Sudanese concentration camps. Agricola takes positive delight in the prospect of looking down from his privileged position (“for as I lie, smiled on, full-fed”) on the non-elect burning in hell. He gets extra satisfaction from gazing at the misery of those who thought that, by doing good, they would at least keep “God’s anger in,” if not altogether win God’s approval. These poor suckers think good deeds will get them to heaven, not realizing that all their “striving” will be “turned to sin”:

For as I lie, smiled on, full-fed

By unexhausted power to bless,

I gaze below on hell’s fierce bed,

And those its waves of flame oppress,

Swarming in ghastly wretchedness;

Whose life on earth aspired to be

One altar-smoke, so pure! to win

If not love like God’s love for me,

At least to keep his anger in;

And all their striving turned to sin.

Priest, doctor, hermit, monk grown white

With prayer, the broken-hearted nun,

The martyr, the wan acolyte,

The incense-swinging child undone

Before God fashioned star or sun!

These poor souls, many apparently Catholic, don’t realize they were damned “before God fashioned star or sun.” The glee that Agricola takes in imagining a child undone may bring to mind those Trumpists unfazed by immigrant children torn from their mothers or killed in Gaza.

As is customary with Browning, the poem ends with a final twist. How would Agricola feel if God did in fact allow such souls to bargain for his love and, through the price of good deeds, end up at his right hand? Well, that would be a God that didn’t live up to the antinomian’s high standards and who would therefore lose his respect and praise:

God, whom I praise; how could I praise,

If such as I might understand,

Make out and reckon on his ways,

And bargain for his love, and stand,

Paying a price, at his right hand?

I suspect that few if any of Trump’s followers label themselves antinomian. But once you start seeing yourselves as elect and others as damned—once you have a mechanism for dismissing your own sins while condemning your enemies to hell—you reveal your kinship with Browning’s Agricola.

Of course, through the dramatic monologue genre Browning reveals his speaker to be guilty of overweening pride, the deadliest of the seven deadly sins. Agricola and many of Trump’s followers, however, would just call this faith that God has singled them out for special favor.