Friday

One of this blog’s goals is to show how an acquaintance with literature can help us through troubled moments. To that end, I love sharing stories about the poems and stories that people turn to. New Yorker’s Masha Gessen, a keen observer of life under autocrats who came to America after fleeing Vladimir Putin, recounts how she has been surfacing an Osip Mandelstam line while agonizing through the last few days.

Appalled that Donald Trump has made the race close, even after separating children from their families, lying daily, and spectacularly botching the Covid pandemic (we are now seeing 100,000 new cases daily), she has been telling herself, “We live without sensing the country beneath us.”

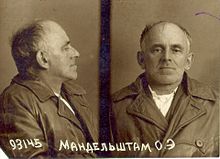

The line is from “Stalin’s Epigram,” a 1933 poem that helped send Mandelstam to the gulag, where he died in 1936. The line, Gessen says,

seemed the best way of describing the state of disorientation and disbelief that marked Tuesday night. Too much of the country wasn’t what any of us thought or hoped it was, whether “we” were my friends and family and me, the mainstream media, the pollsters, or almost anyone I’d heard speak about the election in the last weeks.

Gessen walks us through the poem, choosing from various translations dependent upon which seem more applicable to our situation:

“Our speech is inaudible at ten paces,” reads the next line. We not only don’t know what happens in our country—we cannot speak and be heard; we are deaf to one another, and we are mute. In the time of social isolation, we are indeed almost inaudible at ten paces. We are also barely visible to one another, with half of our faces obscured by masks.

“But where enough meet for half-conversation / The Kremlin hillbilly is our preoccupation” is how Scott Horton translated the next two lines. “They’re like slimy worms, his fat fingers, / His words, as solid as weights of measure.” The brute in charge is inescapable: he is our common obsession and our shared reality. Even as he continues to tear us apart, he brings us together in what conversation there is.

The second stanza, in Clarence Brown and W. S. Merwin’s translation, speaks to “the spectacle of sycophancy, the unceasing performance of dominance,” that we have been witnessing in the Trump administration:

Ringed with a scum of chicken-necked bosses

He toys with the tributes of half men.

One whistles, another meows, a third snivels.

He pokes out his finger and he alone goes boom.

“He alone goes boom” perfectly captures the narcissism, not only of Stalin and Trump, but pretty much of any autocrat.

The following lines compare the decrees of an autocrat to a kick from a horse:

David McDuff translated the next lines as follows: “He forges his decrees like horseshoes— / some get it in the groin, some in the forehead. / some in the brows, some in the eyes.” These lines evoke not only rule by decree but government as attack, as daily bodily assault. “He rolls the executions of his tongue like berries,” the translation by Brown and Merwin goes, and then the penultimate line of the poem: “He wishes he could hug them like big friend back home.”

Given Stalin’s history, “rolling the executions of the tongue like berries” sounds particularly sinister. While Trump doesn’t have the same power to mete out death, the image does get at the ego satisfaction he gets from hearing himself speak at his rallies. He loves his fans—sometimes he talks about kissing and hugging them—but it’s only because they adore him. That love can turn on a dime.

Gessen says that “Stalin’s Epigram” was circulated underground in 1960s Russia and eventually published in the west in the 1970s. Every line, she says, captures

the sense of not knowing where we live and who we share a country with; the stultifying feeling of not hearing and not being heard, of the isolation that is both the precondition and the product of totalitarianism; and most of all, the daily exercise of demonstrative humiliation and deliberate cruelty.

And in conclusion:

It has all happened before; it has been described.

Here’s the poem in its entirety:

Stalin’s Epigram By Osip Mandelstam Trans. W.S. Merwin and Clarence Brown Our lives no longer feel ground under them. At ten paces you can’t hear our words. But whenever there’s a snatch of talk it turns to the Kremlin mountaineer, the ten thick worms his fingers, his words like measures of weight, the huge laughing cockroaches on his top lip, the glitter of his boot-rims. Ringed with a scum of chicken-necked bosses he toys with the tributes of half-men. One whistles, another meows, a third snivels. He pokes out his finger and he alone goes boom. He forges decrees in a line like horseshoes, One for the groin, one the forehead, temple, eye. He rolls the executions on his tongue like berries. He wishes he could hug them like big friends from home.