Monday

It’s not every day that one sees the results of one’s literature class on national television, but such was the case with one of the members of our faculty discussion group last week.

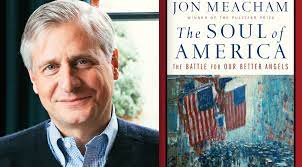

Jon Meacham, Pulitzer-prize winning historian and regular MSNBC commentator, was discussing with Morning Joe host Joe Scarborough Ukrainian president Zelensky’s address to the U.S. Congress. At one point he quoted a passage from George Eliot’s Middlemarch, a work he happened to have read in John Reishman’s Victorian Novels class when Meacham was an English major at Sewanee.

John Reishman, now retired, has led our group’s discussion of Dante’s Divine Comedy and Tennyson’s In Memoriam.

For his part, Meacham was discussing with Scarborough about how Zelensky appears to be “bending history” (Scarborough’s phrase) as he and his country sacrifice everything to hold onto their democracy. The “thrilling and terrifying thing about democracy,” Meacham replied, “is how all of us in the end have the capacity to bend history.” Democracy, he went on to say, is “the fullest manifestation of all of our heart and mind.” Sometimes the only difference between those who visibly bend history and those who don’t is that the former are given an epic scope.

He then went on to cite others who have been given this epic scope, including Winston Churchill, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, John Lewis, the feminists at Seneca Falls, the Selma, Alabama marchers, and the Tiananmen Square protesters. Meacham also mentioned St. Theresa because she is the example cited in Middlemarch. Eliot mentions Theresa in order to set up a contrast with her protagonist, Dorothea Brooke. Here’s what Eliot writes of Theresa:

Theresa’s passionate, ideal nature demanded an epic life: what were many-volumed romances of chivalry and the social conquests of a brilliant girl to her? Her flame quickly burned up that light fuel; and, fed from within, soared after some illimitable satisfaction, some object which would never justify weariness, which would reconcile self-despair with the rapturous consciousness of life beyond self. She found her epos in the reform of a religious order.

Not everyone, however, is given the epic scope of a religious order, Meacham observed—which is precisely Eliot’s point:

That Spanish woman who lived three hundred years ago, was certainly not the last of her kind. Many Theresas have been born who found for themselves no epic life wherein there was a constant unfolding of far-resonant action; perhaps only a life of mistakes, the offspring of a certain spiritual grandeur ill-matched with the meanness of opportunity…

In other words Dorothea, a remarkable woman who longs to accomplish great things, could have been a Zelensky under other conditions. Instead, she finds herself the wife of a narrow-minded pedant.

In his discussion, however, Meacham then made Eliot’s follow-up point. Everyone, he said, can make life a little less difficult for another. These are “the table stakes of democracy.” Quietly making the world a better place is what Dorothea goes on to do:

Her finely touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

Even though Meacham’s comments appeared to have strayed from Zelensky, his point was on target: Zelensky, in fighting for democratic freedom, is fighting for all of us who worry about the rise of authoritarianism, in this country as well as elsewhere. The stakes are immense because, in democracies, each of us matter, even when our acts are unhistoric. If things are “not so ill with you and me as they might have been,” it is because there have been others working invisibly on our behalf.

Democracies call for all of us to be heroic, even though only a few of us capture the limelight.

Further thought: In his remarks, Meacham associated Eliot’s observation with one that Robert Kennedy made in a speech he gave in apartheid South Africa on June 6, 1966. The speech is known as the “ripple of hope” speech because of the following passage:

Thousands of unknown men and women in Europe resisted the occupation of the Nazis and many died, but all added to the ultimate strength and freedom of their countries. It is from numberless diverse acts of courage such as these that the belief that human history is thus shaped. Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

We know about Zelensky but, as the Ukrainian president is the first to point out, he is just the face of all those unknown Ukrainians who are resisting the Russian occupation. Many are dying.