Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Tuesday

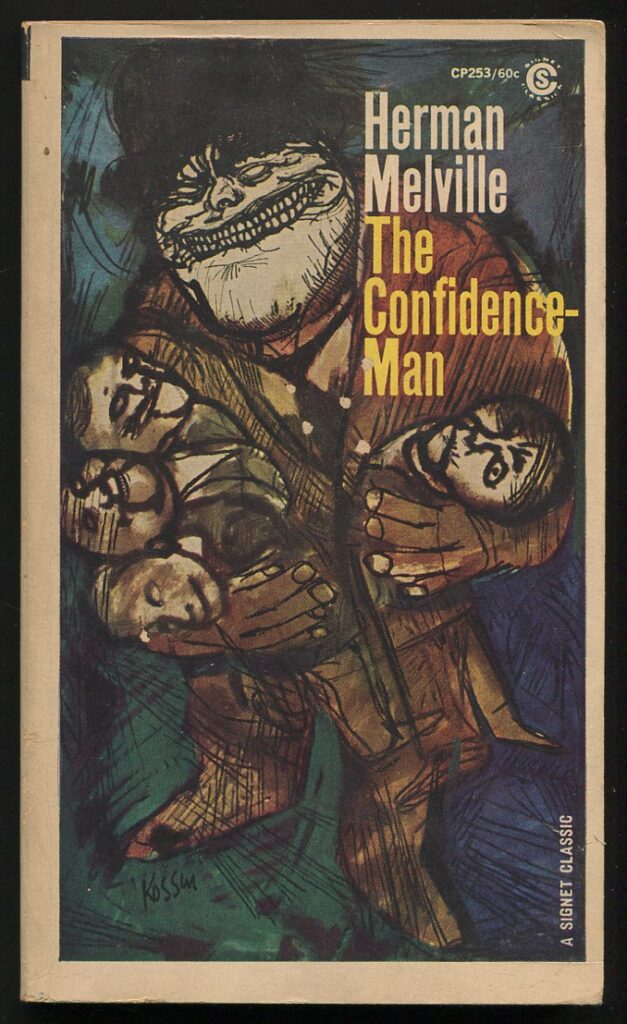

As today (August 1) is Herman Melville’s birthday, I’m reposting a blog essay I wrote seven years ago on The Confidence Man. Donald Trump was running against Hillary Clinton when I wrote it, and Melville’s challenging novel gave me some insights into his political success, although I didn’t realize at the time that his con would eventually pull millions into his orbit.

Confidence Man explains how conmen con, including how a man who has made millions from bilking people could have convinced America that he was more truthful than a former Secretary of State. Whatever her faults, Clinton was fairly honest for a politician, but it was Trump who, despite the 30,000 lies he told while president, still receives plaudits from his supporters for “telling it like it is.”

That Melville provides a compelling depiction of the type (as does Mark Twain with the King and the Duke in Huckleberry Finn) indicates that the figure of the American conman is not new. Sadly, Trump has not only tapped into this history but has taught wannabe imitators to follow suit. When Melville’s barber dismisses “sheepish” truth and declares, “Lies, lies, sir, brave lies are the lions!”, he provides a template for all those politicians and enablers who conjure up “alternate facts” out of thin air. Some of them (Steve Bannon, Roger Stone) even announced publicly and ahead of time that they would be lying about the 2020 election if it didn’t go Trump’s way. As Stone, knowing that Trump might well be ahead election night before mail-in ballots started arriving, advised,

I really do suspect it’ll still be up in the air. When that happens, the key thing to do is to claim victory. Possession is nine tenths of the law. “No, we won. Fuck you, Sorry. Over. We won. You’re wrong. Fuck you.”

French epigrammatist François de La Rochefoucauld famously said that “hypocrisy is the homage that vice pays to virtue,” but Trump has taught his wannabe imitators that they need not pay that homage. Don’t tilt your hit to being good. Just make things up.

Occasionally we have seen some accountability. Fox News has had to pay almost a billion dollars when its commentators lied about Dominion voting machines changing votes; several Trump lawyers are facing disbarment for repeating his false claims and pressing frivolous lawsuits; and those whose lies ruined the lives of two Georgia election workers may have to pay severe fines. In other words, our society hasn’t totally dispensed with truth.

But the MAGA right is certainly going after society’s truth adjudicators, especially judges, lawyers, journalists, health professionals, and academics (all of whom can be drummed out of their professions if they make baseless claims or engage in unethical behavior). If the final guardrails that separate truth from falsehood are ever removed, then power will devolve to those who can tell—and then back up with force—the most effective lies.

But for the moment, take your mind back to a time when Trump was still a longshot candidate. Literature’s ability to grasp the essence of such a man makes it yet another essential adjudicator of truth.

Reprinted from August 15, 2023

One of the most memorable lines for me from the National Democratic Convention was New York billionaire Michael Bloomberg saying about Donald Trump, “I am from New York and I know a con when I see one.” Since then, I’ve been reading Herman Melville’s The Confidence Man to see if it will give me insights into the nature of Trump’s con.

I’ll be turning to the novel a number of times during this election season, but let me start with this. Melville helps explain why, as Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times puts it, “One persistent narrative in American politics is that Hillary Clinton is a slippery, compulsive liar while Donald Trump is a gutsy truth-teller.” In a recent NBC poll, only 11% of voters chose to describe Clinton as “honest and trustworthy” (as opposed to 16% for Trump).

Even the idea that Clinton and Trump are in the same category Kristof finds to be preposterous. “If deception were a sport,” he writes, “Trump would be the Olympic gold medalist; Clinton would be an honorable mention at her local Y.”

A study by Politifact of presidential candidates since 2007 bears Kristof out. Clinton is second only to Obama in truthfulness, finishing ahead of Jeb Bush and Bernie Sanders. Trump, on the other hand, leads everyone in lying, even Michele Bachman and Ted Cruz. One of the characters in The Confidence Man explains why we may find ourselves surprised by Hillary’s high rating.

Melville’s novel is about a flimflam artist who boards a steamboat and dons a series of disguises to bamboozle the passengers. At one point he goes to work on the ship’s barber, who has put a “No Trust” sign—meaning no credit—in his window. The confidence man convinces him to start trusting people, after which he wriggles out of paying for his shave.

The barber helps us understand how Trump makes his lies compelling, even getting at the way the Trump’s flamboyant hair gives him confidence. (The barber also gets at Trump’s underlying insecurity–without such hair, the barber says, a man is shamefaced and fearful.) We also learn why Clinton’s careful word choices damage her as much as Trump’s “pants on fire” “four Pinocchios” fabrications. Responding to the question, “how does the mere handling of the outside of men’s heads lead you to distrust the inside of their hearts?”, the barber replies,

[C]an one be forever dealing in macassar oil, hair dyes, cosmetics, false moustaches, wigs, and toupees, and still believe that men are wholly what they look to be? What think you, sir, are a thoughtful barber’s reflections, when, behind a careful curtain, he shaves the thin, dead stubble off a head, and then dismisses it to the world, radiant in curling auburn? To contrast the shamefaced air behind the curtain, the fearful looking forward to being possibly discovered there by a prying acquaintance, with the cheerful assurance and challenging pride with which the same man steps cheerful assurance and challenging pride with which the same man steps forth again, a gay deception, into the street, while some honest, shock-headed fellow humbly gives him the wall!

And then the passage that explains Clinton’s problem:

Ah, sir, they may talk of the courage of truth, but my trade teaches me that truth sometimes is sheepish. Lies, lies, sir, brave lies are the lions!”

So there you have it: Trump tells brave lies whereas Hillary engages in sheepish equivocations.

The follow-up passage has relevance to the Trump campaign as well. When the confidence man accuses the barber of participating in a fraud, the man replies, “”Ah, sir, I must live.”

This sounds very much like the ghostwriter who wrote Trump’s The Art of the Deal and now, according to Jane Mayer’s remarkable, is wracked with guilt. Like the barber, he says that he did it because he had bills to pay:

Around the time Trump made his offer, [Tony] Schwartz’s wife, Deborah Pines, became pregnant with their second daughter, and he worried that the family wouldn’t fit into their Manhattan apartment, whose mortgage was already too high. “I was overly worried about money,” Schwartz said. “I thought money would keep me safe and secure—or that was my rationalization.”

What happens when we dance with a professional confidence man? We get conned. Why are we surprised?

Further thought: Professor Ruth Ben-Ghiat, an authority on strong men figures who believes that Trump is “a competent authoritarian,” cites another expert on authoritarianism to get at the danger Trump poses:

As for Trump’s grass-roots supporters, he has taken millions of them closer to a situation that the philosopher Hannah Arendt identified as critical for the success of authoritarian rule. As she wrote in The Origins of Totalitarianism, “the ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.”