I love having science majors in my literature classes. Few things dramatize the value of a liberal arts education more than seeing students use literature to sort through issues raised by evolutionary biology or particle physics. This past semester Amanda Rankin used Paradise Lost to grapple with questions prompted by her biology major.

Amanda began her essay with an eye-catching assertion:

If there were a fruit that would give me all the knowledge in the world upon tasting it, I would eat it in a heartbeat.

That at any rate is what she initially thought. As she explored Milton’s epic further, however, she began to accept that there were questions she would never be able to answer.

Amanda explained her desire for the forbidden fruit by discussing her frustrations with not being omniscient:

While I recognize [that I can’t know everything], I nevertheless find it frustrating. Throughout my life, I have struggled with the awareness that I cannot be certain of anything: that we know the truth about the distant past, that our understanding of the natural world is correct, or even that I am giving someone correct advice. I am obsessed with correctness. Uncertainty has a tendency to unnerve me since I want to always be able to do what is best and not accidentally make things worse… I want to utilize this knowledge to better the whole world, as I believe such knowledge should be used. In a way that relates more to the everyday, I often find myself wishing I could be omniscient just so I could tell people whether they are making the right decisions to achieve their happiness. I wish I could direct friends and family members toward what they truly need to be happy, without any sort of guesswork.

Paradise Lost alerted her that desires she thought were innocent were in fact motivated by pride:

[M]any pursue knowledge for ulterior motives, normally ones perceived at the time as good reasons. My desire for total knowledge is a wish to escape my inner doubts and to also act as a savior to the world. These motives reflect a lack of true faith in God as well as in myself. By asking for omniscience, I inherently believe that, with such knowledge, I could do something with it that God does not or even could not. Such a desire is deeply prideful…

Amanda made an important distinction in her discussion. There is nothing wrong with pursuing knowledge to appreciate the world more. In fact, the angel Raphael, sent to instruct Adam (but not, given 17th century sexism, Eve), points out that knowledge can be used “the more to magnify [God’s] works.” That knowledge must, however, be “within bounds”:

[S]uch commission from above

I have received, to answer thy desire

Of knowledge within bounds…

The problem occurs when humans attempt to usurp God’s place—which is to say, when we use knowledge to become God-like ourselves, thereby cutting ourselves off from God’s wisdom and goodness. Continuing his instructions, Raphael cautions Adam to abstain from inquiring further. Do not, he says, “let thine own inventions hope things not revealed.”

God is not hoarding knowledge in order to keep humans in subjection, Amanda noted, although this is what Satan claims and what Eve comes to believe. Rather, God, being God, knows what humans need to find deepest fulfillment, which is to be in harmony with God (or to be in harmony with the universe if you don’t like the word “God”). When humans seek to elevate themselves above creation, they bring destruction upon it.

Amanda was struck by Milton’s comparison of ego-motivated knowledge to gluttony:

But knowledge is as food, and needs no less

Her temperance over appetite, to know

In measure what the mind may well contain,

Oppresses else with surfeit, and soon turns

Wisdom to folly, as nourishment to wind.

About which Amanda wrote:

[G]luttony…is not being satisfied with the food the body needs and overindulging for the sake of temporary pleasure. Knowing too much will turn any wisdom seemingly acquired into foolishness, just as eating too much can cause indigestion.

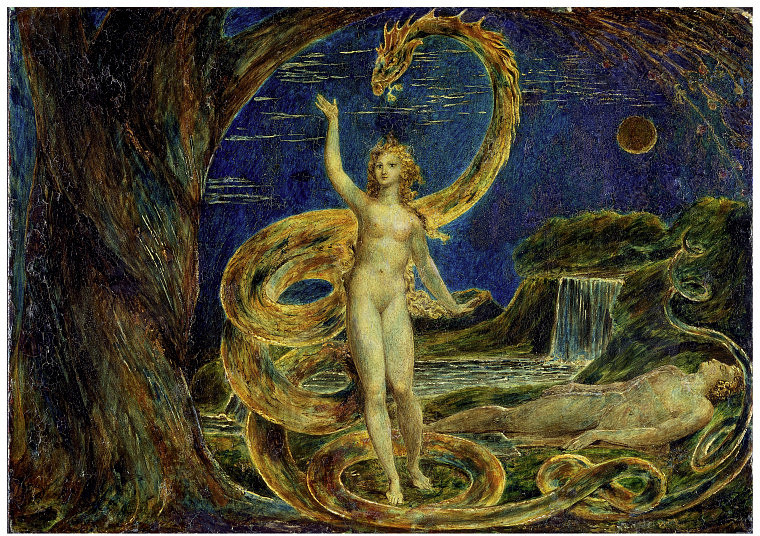

Amanda noted that, even before encountering the fruit, Eve can be seen as egotistical, as in her expressed desire to show her mettle by standing up to Satan:

Though she is right in saying they would gain honor from withstanding such temptation, she clearly wants this glory for herself individually. If she felt content with shared glory for them both, she would feel content to remain by Adam’s side. Instead, she desires to be tested and to prove true, perhaps to prove to herself that she does not need to rely fully on Adam. These ambitions get played on by Satan, disguised as a serpent with the gift of human speech, when he tells her to look on his example and see that he has eaten of the fruit and has not only lived but also gained human qualities.

Satan’s speech in praise of the forbidden fruit captures the arrogance of any number of scientists:

O Sacred, Wise, and Wisdom-giving Plant,

Mother of Science, Now I feel thy Power

Within me clear, not only to discern

Things in their Causes, but to trace the way

Of highest Agents, deemed however wise.

Eve, upon tasting the fruit, likewise turns her attention from God to her own growing wisdom:

O Sovran, virtuous, precious of all Trees

In Paradise, of operation blest

To Sapience, hitherto obscured, infamed

And thy fair Fruit let hang, as to no end

Created; but henceforth my early care,

Not without Song, each Morning, and due praise

Shall tend thee, and the fertil burden ease

Of thy full branches offer’d free to all;

Till dieted by thee I grow mature

In knowledge, as the Gods who all things know…

At one point in her essay, Amanda mentioned human restlessness, a concept she picked up from her favorite George Herbert poem, “The Pulley.” I mentioned to her that this was also the favorite poem of Robert Oppenheimer, who famously pushed scientific knowledge in a Satanic direction through his work on the atomic bomb. For Amanda to associate such restlessness with human pride means that she is undertaking a self-examination that we should wish for from all our scientists.

In our quest for knowledge, we can’t always be certain whether we are honoring the universe or simply seeking to elevate ourselves. What we can do, however, is what Amanda does: probe our own motivations and, out of that probing, make the best decisions that we can. When we do so, we are less likely to do harm. Amanda lets us know that literature in an invaluable resource in the process.

One Trackback

[…] “The Pulley,” which I’ve written about here and mentioned here, Herbert describes restlessness as intrinsic to the human condition, and it certainly shows up in […]