Tuesday

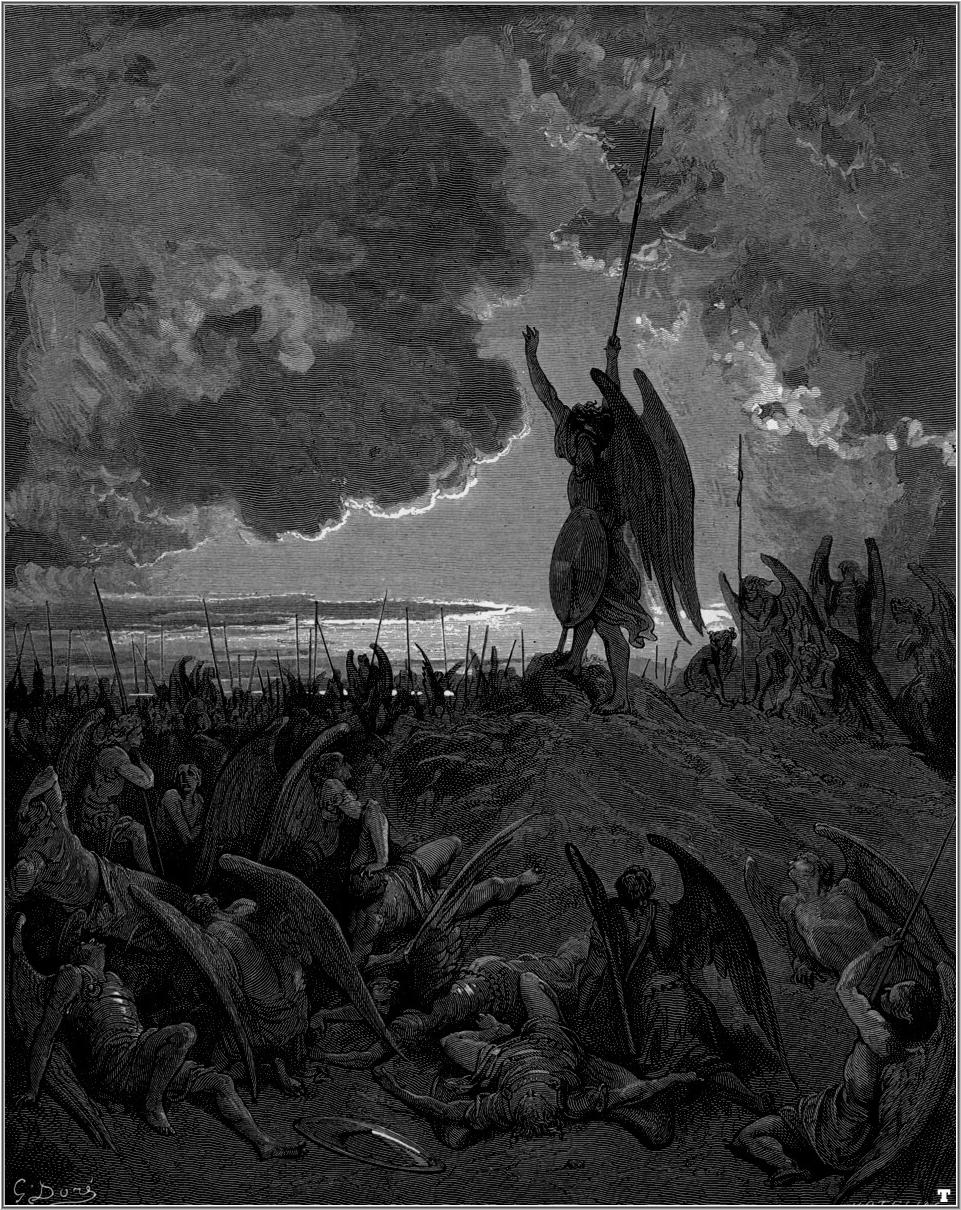

Reader Ruth Arseneault alerted me to a fine article in The Atlantic about the impact of Milton’s Satan upon the American imagination. Edward Simon shows how many of television’s most popular antiheroes, such as Walter White, Don Draper, and Tony Soprano, can be traced back to Satan, sometimes by way of Melville’s Captain Ahab. Satan, Simon argues, is quintessentially American.

Simon doesn’t mention Trump in his article, but perhaps he doesn’t need to. I’ve been making Lucifer-Trump associations for a while, however, including in my favorite post from last year. In it I argued that, just as Satan unleashes Sin and Death upon the world, so Trump gives the worst elements of America a “dark permission” to engage in hateful language and action.

Here’s what Simon has to say about Satan’s presence in America:

Curiously, the deeply modern Lucifer could also be considered one of the greatest characters in American literature, even though he was created more than a century before the United States was founded.

That’s in part because literary critics have decked Lucifer’s creator himself in red, white, and blue bunting since the 19th century. In 1845, Rufus Griswold wrote that Milton was “more emphatically American than any author who has lived in the United States.”

And:

Many of the values the archangel advocates in Paradise Lost—the self-reliance, the rugged individualism, and even manifest destiny—are regarded as quintessentially American in the cultural imagination. Milton may be a poet of individual liberty and conscience, but he was also one of the most brilliant theological explorers of the darker subjects of sin, depravity, and the inclination toward evil. Nothing demonstrates that inclination more than the long-standing appeal the charismatic Lucifer has had for audiences, an appeal mirrored by the flawed but alluring protagonists of some of TV’s greatest American dramas. What Milton’s Paradise Lost, the first version of which was published in 1667, also demonstrates is what can be so dangerous about mistaking an antihero for a hero.

And:

[Lucifer] is a conflicted, brooding, alienated, narcissistic self-mythologizer. In other words, he’s a thoroughly modern man, and in a country as preoccupied with modernity as the United States is, he’s arguably an honorary “American” as a result. Milton’s fellow countryman, the novelist D.H. Lawrence, remarked in his under-read 1923 Studies in Classic American Literature that, “The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer. It has never yet melted.” The novelist had in mind not just the pioneer clearing lands that do not belong to him, but also the honey-worded con man who can justify his crimes in the sweetest language.

I’m currently teaching Paradise Lost and we have been wrestling with Satan’s charisma. I’m always look for the point when my students begin to turn against the archangel. Often it’s when he decides to make Adam and Eve pay for his own unhappiness.

The very fact that we find ourselves attracted to Satan, however, shows just how dangerous he is. I’ve long been convinced that Blake was wrong: Milton was not of the devil’s party without knowing it but rather out to show just how seductive this con angel could be. Now that we’ve seen our own Satan con his way into the presidency, it’s worth looking at what happens next in the poem.

As long as Satan was promising his followers great things if they would follow him into battle with God, he didn’t have to face the consequences. They could imagine the fulfillment of all their desires. However, once he butted up against reality (God), everything goes bad very quickly. Although Satan’s magnificent rhetoric is able to hold onto the allegiance of the fallen angels until the very end, their lifestyle takes a severe blow. Imagine relocating from Heaven to

A Dungeon horrible, on all sides round

As one great Furnace flam’d, yet from those flames

No light, but rather darkness visible

Served only to discover sights of woe,

Regions of sorrow, doleful shades, where peace

And rest can never dwell, hope never comes

That comes to all; but torture without end

Still urges, and a fiery Deluge, fed

With ever-burning Sulphur unconsumed…

Instead of taking responsibility for his broken promises, however, Satan sees himself as the aggrieved party. It’s all God’s fault! He talks a populist line, claiming to fight for liberty against tyranny, even as he himself sits on a

a Throne of Royal State, which far

Outshone the wealth of Ormus and of Ind,

Or where the gorgeous East with richest hand

Showers on her Kings Barbaric Pearl and Gold…

(It sounds like the Trump’s gold-plated penthouse apartment.)

Above all, Satan creates his own internal reality. Simon cites and comments on a key passage:

In Mad Men’s very first episode, Don Draper memorably remarks, “What you call love was invented by guys like me… to sell nylons,” which recalls Lucifer’s famous assertion that “The mind is its own place, and in itself / Can make a heav’n of hell, a hell of heav’n.” Lucifer is not just a rebel, but also a character who has tricked himself (and many of his post-Romantic readers) into believing his very words can generate reality. Lucifer’s line is a pithy and dark summation of the American credo of self-invention. His mercurial nature and his rhetorical chicanery recall the verbal dexterity of Draper, who, like Lucifer, shed his original name.

When he proves unable to make heaven of hell, Satan doesn’t relent but doubles down. Now revenge, not any well-thought-through policy position, is uppermost in his mind. Unfortunately, he’s cunning enough to make life miserable for some decent people.

Who will save us from our own bad angels? That’s what voting is for.