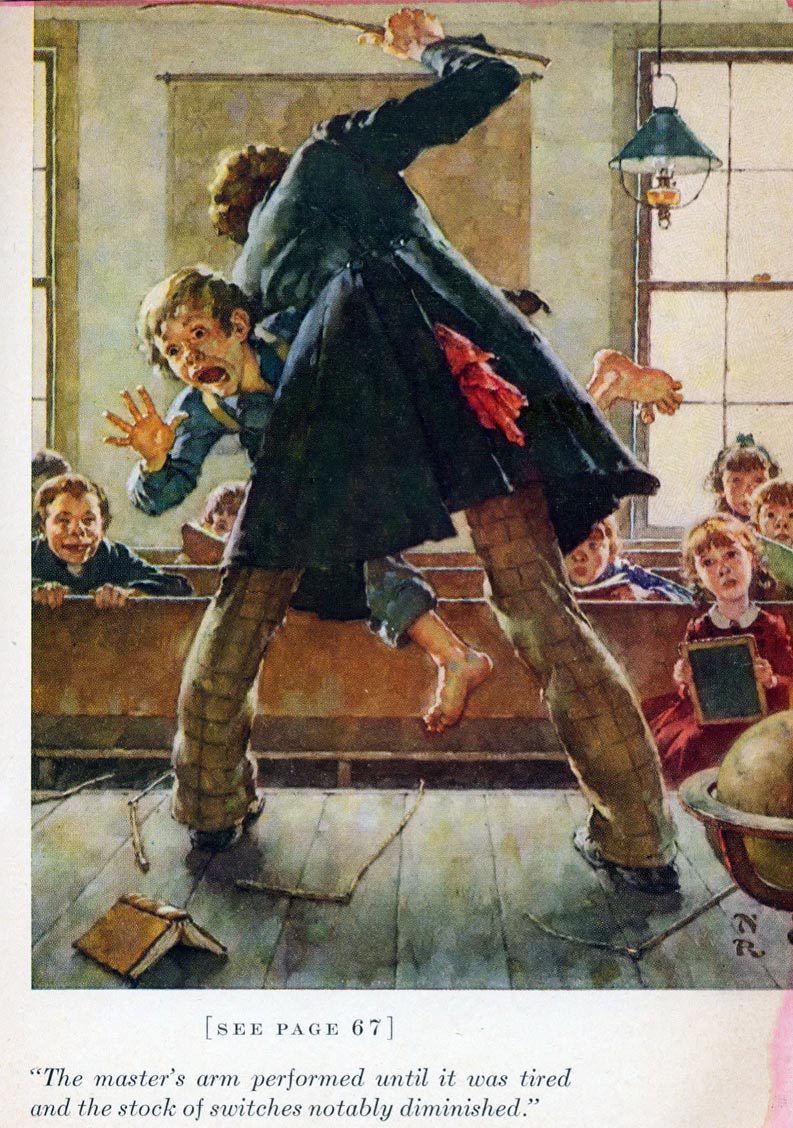

Norman Rockwell, from Tom Sawyer

Jason Blake’s guest column this week is on the issue of plagiarism. Jason’s experience matches my own: it takes more work to produce a successful plagiarism than to write an acceptable essay. Plagiarism is generally so obvious that the plagiarist resembles Tom Sawyer in the episode involving memorized Bible verses. As you may recall, students in Tom’s Sunday school get tickets for each Bible verse they memorize. Tom buys up a mass of tickets from the other kids (with proceeds he has gotten from “allowing” them to whitewash the fence) and wins the competition. Unfortunately, this means that he also must answer a question from a visiting Presbyterian elder. Asked who were the first two disciples, Tom thrashes around before finally answering, in desperation, “David and Goliath.”

By Jason Blake, University of Ljubljana, English Department

The closed world of the university and its individual courses is very game-like. There are clear rules about how grades are awarded, relatively few consequences for life beyond ENG 101, and the entire routine rests on a communal faith that discussing Hamlet for the umpteenth time in the umpteenth course is worthwhile. Classroom discussion and essays are a chance to try out ideas with relative impunity. This is the same as in the world of baseball, soccer, Risk and Monopoly, with their arbitrary rules unquestioningly and reverently accepted for the length of the game.

We even have the occasional cheater, which is pudding-proof that university is like poker at times.

In a recent opinion piece called “Plagiarism Is Not a Big Moral Deal,” Stanley Fish highlights the apartness of the campus, including its plagiarism taboo. His blog essay is less risqué than the title implies, and nowhere does he hint that plagiarizers should go scot-free. He writes about cheaters with (probably feigned) insouciance bordering on irony: “The rule that you do not use words that were first uttered or written by another without due attribution is less like the rule against stealing […] than it is like the rules of golf.” Downright kooky restrictions, it seems to the non-golfer. Fish then states that “if you’re a student, plagiarism will seem to be an annoying guild imposition without a persuasive rationale (who cares?).”

The word “plagiarism,” like “abortion,” “gun control” and “socialized health care,” makes people see red, and comments to Fish’s column were hasty and virile, even viral (no surprise, with a baiting title like the one he chose). Though obviously aware of it, Fish ignores the educational tragedy of plagiarism: if you borrow words, you’re not developing your own thinking skills and thus missing the whole point of university. To push the game or sport analogy, plagiarizing or cheating is like writing down miles in the runner’s log without having done the legwork. If the goal is to fool your coach/teacher, you might; if the goal is to improve your physical/mental abilities, you won’t.

Some have quipped that North American universities teach deadlines more than anything else. A Shakespeare course begins in September and finishes in December, come hell or high-water; on December 10, starting at 9am, you will have exactly 90 minutes to write a final test. This rigidity is like the parallel clock of many sports. If you have a bad exam day, tough luck. Tell it to the star running back who fumbles in the Super Bowl, or the sprinter who trips over the tenth hurdle on her way to Olympic glory. (Continental European universities have a much more relaxed attitude to deadlines and exams – at my university students have up to five cracks at certain exams; they have up to two years to hand in a term paper.) I’m sure the thesis has been floated that this time-pressure invites plagiarism.

In Douglas Adams’ novel Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency, Dirk makes some pocket money while studying at Cambridge by helping his classmates cheat. Sort of. He sells probable exam questions, slyly marketing them as “exam papers.” There is talk of hypnosis and automatic writing, but really young Dirk is just being a crafty student. He predicts the questions by “doing the same minimum research that any student taking exams would do, studying previous exam papers and seeing what, if any, patterns emerged, and making intelligent guesses about what might come up. He was pretty sure of getting (as anyone would be) a strike rate that was sufficiently high to satisfy the credulous, and sufficiently low for the whole exercise to look perfectly innocent.” In other words, Dirk isn’t really cheating, just lying to his fellow students.

Remember when geeky Niles on Frasier nails a basket from half-court during halftime at a Supersonics game? The same sort of thing happens with Dirk. One year “all the exam papers he sold turned out to be the same as the papers that were actually set. Exactly. Word for word. To the very comma.” Dirk avoids major punishment because nobody can prove that he actually stole the exams. This is accidental plagiarism at its finest. Statistically speaking, it is a lexical and syntactical miracle, but not impossible.

The problem with most student plagiarism is that it is boring. There is no Gently-esque spark of illicit genius or even wiliness feeding it. This is probably because stealing a paper that raises no suspicions is harder to produce than an original essay, and the plagiarist rarely has time on his side. Most students don’t steal an entire paper, which is a tactical mistake because any experienced reader can tell in an instant when the tone or style changes.

As a former lazy student, I can tell you exactly how this catch-me plagiarism happens: the student finds himself in a time-pinch, perhaps devoid of ideas or uninspired by an assignment, and hands in an ill-begotten paper just for the sake of it. (For the record, my understanding is a step removed. I never cheated. My policy was to hand in rubbish on time.) This is educational role-playing at its worst. The teacher asks for the goods, the student uncaringly coughs them up, and both can finish the term saying they’ve done their job.

What’s more, being able to say, “I caught four little cheaters this term!” is great for an educator’s reputation for strictness. Word spreads quickly: five years ago I had three or four plagiarized papers. Last year I had none. Maybe they’re just getting better.

When there is no real attempt to hide the stolen words, plagiarism is impossible to miss: the text spacing changes between paragraphs; “colour” in the introduction becomes “color” in the conclusion; the font color lightens from black to dark grey; Times New Roman, 11 becomes Courier New, 12; a hyperlink sneaks into paragraph three. All of these common examples indicate a cut-and-paste operation, and all of them bring to mind the hapless thief who leaves his wallet and ID at the scene of the crime.

What is missing here is the “sportive element,” what Leonard Bernstein (quoting another conductor) summed up as the “factor of curiosity, adventure, experiment” that exists in music-making and play of all sorts. Something that young people have in abundance. You’d hope that even (especially?) when cheating, students would show more creativity and zest, less intellectual laziness. When I see such weak plagiarism, I wonder if the cheater wants to be caught, if she’s daring me to call her bluff.

And so, in a spirit of defeat, and with a nod to the inevitability of future plagiarists, let me end with advice attributed to Martin Luther: “If you must sin, sin nobly!” Do it with pizzazz and with a nose for beating the system. If I catch you, of course, the grade is still zero. But at least make a game of it.

Be like Gloucester in the first scene of King Lear, when he admits that his bastard son Edmund “came something saucily into the world” and that “there was good sport at his making.” And please admit it right away. Floyd Landis looked ridiculous denying that he juiced up for part of the 2006 as test after test confirmed he had.

Even better, just write the paper yourself. After all, it’s your education.

Jason Blake is the author of Canadian Hockey Literature (University of Toronto, 2010).