Wednesday

This past semester, somewhat on impulse, I taught “The Existential Fantasies of Haruki Murakami” for my first year seminar course. (For years I have been teaching Jane Austen’s novels in the seminar but feared that I was becoming stale.) I didn’t know how my students would respond to Murakami but figured that there were two things in the course’s favor.

First, since the Japanese author is attracting readers all over the world, he might also attract Maryland students. Second, late adolescence is a time when young people wrestle with life’s big questions so a course on existential fantasies might hit them where they live.

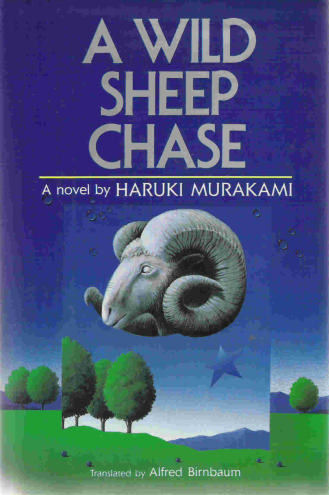

Both assumptions proved correct, as I will demonstrate in a series of posts. Today I share two students’ responses to Wild Sheep Chase (1982), Murakami’s third novel and the first one we read. The novel spoke to the ideals of an ardent Bernie Sanders supporter, and it helped another student come out of the closet, which he did in his class presentation (!).

The novel is well titled. The narrator protagonist, whom critics refer to as Boku since we never learn his actual name (Boku is the informal Japanese “I”), is living a dull life producing advertising fliers when suddenly he finds himself embarking upon a strange quest. A shadowy organization that controls Japan’s marketing industry, mass media, and government contacts him about a pastoral illustration of a strange sheep that has appeared on one of his brochures. A shadowy figure—the class called him “Mr. Big”—gives Boku a month to track down the sheep. If he fails, he will lose his business and be blackballed for the rest of his life.

It turns out (spoiler alert) that there is a strange sheep spirit on the loose looking for a capable host. Genghis Khan was a beneficiary of this sheep spirit in the past and, in the 1930s it entered a Japanese fascist, who went on to found the shadowy organization. Now, however, the man is dying, and his second-in-command, Mr. Big, wants to inherit the sheep spirit to keep the organization going. For tangled plot reasons, he needs Boku to set up the necessary contact.

The novel functions as a parable of life in contemporary Japan. Murakami sees the Japanese as sheep-like, all too ready to follow an authoritarian head ram wherever he leads them. Boku is an every man, going through a series of empty relationships and generally leading a life (to borrow from Thoreau) of quiet desperation. My Bernie supporter quoted the following passage to characterize his existence:

I was twenty-one at the time, about to turn twenty-two. No prospect of graduating soon, and yet no reason to quit school. Caught in the most curiously depressing circumstances. For months I’d been stuck, unable to take one step in any new direction. The world kept moving on; I alone was at a standstill. In the autumn, everything took on a desolate cast, the colors swiftly fading before my eyes. The sunlight, the smell of the grass, the faintest patter of rain, everything got on my nerves.

The quest to find the sheep jolts Boku out of this existence, and suddenly he is reading up on Japanese history and interacting with nature in a rural Japanese setting. Color begins to return to his life. By the end of the novel, he is able to thwart the shadowy corporation, and he begins to live life deliberately. He is no longer a placid sheep but is marching to the beat of his own drummer.

You can see why the novel would appeal to a Bernie enthusiast and, for that matter, anyone worried about leaders with authoritarian tendencies. The fact that Donald Trump is turning a lot of people into sheep means that Americans need to join Boku and push back.

My closeted student, meanwhile, learned that, to claim one’s essential identity, one must be willing to stand strong against the shadowy corporations that set the rules and appear to define reality. It took courage for him to come out, and Murakami provided him a useful narrative.

Literature can do heavy lifting, I tell my students. These two students took advantage of that potential.