Thursday

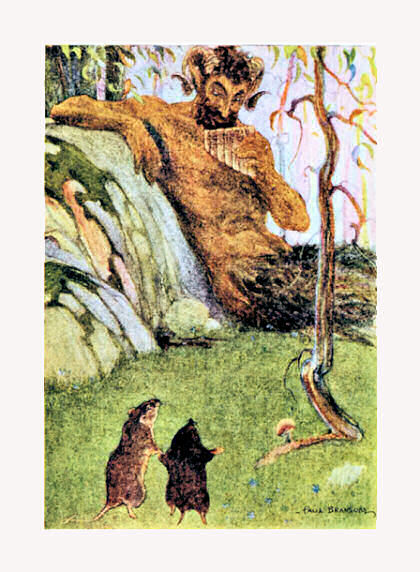

As I’m currently traveling, I’m reposting an essay I wrote seven years ago about a poem by Xavier University’s Norman Finkelstein, whom we dined with last night. Norman was my best friend in graduate school and this may be my favorite of his poems, perhaps because I too am in love with Kenneth Graham’s Wind in the Willows, especially the Pan episode in “Piper at the Gates of Dawn.”

Reposted from Nov. 18, 2012

Kenneth Grahame’s 1908 classic The Wind in the Willows has one of the most haunting literary episodes I know, an expression of early 20th century pantheism or neopaganism where Rat and Mole come face to face with godhead. The book itself owes its title to a moment in the book when Rat tries to capture on paper a distant voice that he hears. The scene inspired a wonderful poem by my best friend in graduate school, Norman Finkelstein, who gave me permission to share it with you.

In the Grahame episode, Rat and Mole have gotten up before dawn to find an otter child who is missing. Rat, who is a poet, senses the presence of divinity first, but eventually even the more pedestrian Mole picks up on it. Here they are as dawn begins to break:

Fastening their boat to a willow, the friends landed in this silent, silver kingdom, and patiently explored the hedges, the hollow trees, the runnels and their little culverts, the ditches and dry water-ways. Embarking again and crossing over, they worked their way up the stream in this manner, while the moon, serene and detached in a cloudless sky, did what she could, though so far off, to help them in their quest; till her hour came and she sank earthwards reluctantly, and left them, and mystery once more held field and river.

Then a change began slowly to declare itself. The horizon became clearer, field and tree came more into sight, and somehow with a different look; the mystery began to drop away from them. A bird piped suddenly, and was still; and a light breeze sprang up and set the reeds and bulrushes rustling. Rat, who was in the stern of the boat, while Mole sculled, sat up suddenly and listened with a passionate intentness. Mole, who with gentle strokes was just keeping the boat moving while he scanned the banks with care, looked at him with curiosity.

`It’s gone!’ sighed the Rat, sinking back in his seat again. `So beautiful and strange and new. Since it was to end so soon, I almost wish I had never heard it. For it has roused a longing in me that is pain, and nothing seems worth while but just to hear that sound once more and go on listening to it for ever. No! There it is again!’ he cried, alert once more. Entranced, he was silent for a long space, spellbound.

`Now it passes on and I begin to lose it,’ he said presently. `O Mole! the beauty of it! The merry bubble and joy, the thin, clear, happy call of the distant piping! Such music I never dreamed of, and the call in it is stronger even than the music is sweet! Row on, Mole, row! For the music and the call must be for us.’

The Mole, greatly wondering, obeyed. `I hear nothing myself,’ he said, `but the wind playing in the reeds and rushes and osiers.’

The Rat never answered, if indeed he heard. Rapt, transported, trembling, he was possessed in all his senses by this new divine thing that caught up his helpless soul and swung and dandled it, a powerless but happy infant in a strong sustaining grasp.

Further on Mole tunes in:

Breathless and transfixed the Mole stopped rowing as the liquid run of that glad piping broke on him like a wave, caught him up, and possessed him utterly. He saw the tears on his comrade’s cheeks, and bowed his head and understood. For a space they hung there, brushed by the purple loose-strife that fringed the bank; then the clear imperious summons that marched hand-in-hand with the intoxicating melody imposed its will on Mole, and mechanically he bent to his oars again. And the light grew steadily stronger, but no birds sang as they were wont to do at the approach of dawn; and but for the heavenly music all was marvellously still.

On either side of them, as they glided onwards, the rich meadow-grass seemed that morning of a freshness and a greenness unsurpassable. Never had they noticed the roses so vivid, the willow-herb so riotous, the meadow-sweet so odorous and pervading. Then the murmur of the approaching weir began to hold the air, and they felt a consciousness that they were nearing the end, whatever it might be, that surely awaited their expedition.

A wide half-circle of foam and glinting lights and shining shoulders of green water, the great weir closed the backwater from bank to bank, troubled all the quiet surface with twirling eddies and floating foam-streaks, and deadened all other sounds with its solemn and soothing rumble. In midmost of the stream, embraced in the weir’s shimmering arm-spread, a small island lay anchored, fringed close with willow and silver birch and alder. Reserved, shy, but full of significance, it hid whatever it might hold behind a veil, keeping it till the hour should come, and, with the hour, those who were called and chosen.

Slowly, but with no doubt or hesitation whatever, and in something of a solemn expectancy, the two animals passed through the broken tumultuous water and moored their boat at the flowery margin of the island. In silence they landed, and pushed through the blossom and scented herbage and undergrowth that led up to the level ground, till they stood on a little lawn of a marvellous green, set round with Nature’s own orchard-trees — crab-apple, wild cherry, and sloe.

`This is the place of my song-dream, the place the music played to me,’ whispered the Rat, as if in a trance. `Here, in this holy place, here if anywhere, surely we shall find Him!’

Then suddenly the Mole felt a great Awe fall upon him, an awe that turned his muscles to water, bowed his head, and rooted his feet to the ground. It was no panic terror — indeed he felt wonderfully at peace and happy — but it was an awe that smote and held him and, without seeing, he knew it could only mean that some august Presence was very, very near. With difficulty he turned to look for his friend. and saw him at his side cowed, stricken, and trembling violently. And still there was utter silence in the populous bird-haunted branches around them; and still the light grew and grew.

Perhaps he would never have dared to raise his eyes, but that, though the piping was now hushed, the call and the summons seemed still dominant and imperious. He might not refuse, were Death himself waiting to strike him instantly, once he had looked with mortal eye on things rightly kept hidden. Trembling he obeyed, and raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fulness of incredible colour, seemed to hold her breath for the event, he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper; saw the backward sweep of the curved horns, gleaming in the growing daylight; saw the stern, hooked nose between the kindly eyes that were looking down on them humourously, while the bearded mouth broke into a half-smile at the corners; saw the rippling muscles on the arm that lay across the broad chest, the long supple hand still holding the pan-pipes only just fallen away from the parted lips; saw the splendid curves of the shaggy limbs disposed in majestic ease on the sward; saw, last of all, nestling between his very hooves, sleeping soundly in entire peace and contentment, the little, round, podgy, childish form of the baby otter. All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.

Rat!’ he found breath to whisper, shaking. `Are you afraid?’

`Afraid?’ murmured the Rat, his eyes shining with unutterable love. `Afraid! Of Him? O, never, never! And yet — and yet — O, Mole, I am afraid!’

Then the two animals, crouching to the earth, bowed their heads and did worship.

After the moment, the vision vanishes. It is this moment, as you will see, that captures my friend’s attention:

Sudden and magnificent, the sun’s broad golden disc showed itself over the horizon facing them; and the first rays, shooting across the level water-meadows, took the animals full in the eyes and dazzled them. When they were able to look once more, the Vision had vanished, and the air was full of the carol of birds that hailed the dawn.

As they stared blankly. in dumb misery deepening as they slowly realised all they had seen and all they had lost, a capricious little breeze, dancing up from the surface of the water, tossed the aspens, shook the dewy roses and blew lightly and caressingly in their faces; and with its soft touch came instant oblivion. For this is the last best gift that the kindly demi-god is careful to bestow on those to whom he has revealed himself in their helping: the gift of forgetfulness. Lest the awful remembrance should remain and grow, and overshadow mirth and pleasure, and the great haunting memory should spoil all the after-lives of little animals helped out of difficulties, in order that they should be happy and lighthearted as before.

And now, here’s Norman’s poem, which uses as its epigraph the final line of the passage I just quoted:

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn

By Norman Finkelstein

We little animals living by the river banks

burrowers and swimmers by sandy shores:

was there ever a time when the bird’s song,

giving way in evenng to the flight of the bat,

failed to presage a momentary chill,

even on summer days?

Yes, we are full of Panic life;

it flows deep within us, nor are we out of touch

with the powers that watch us survive.

But the banks get crowded

or fall away steeply,

and someone is always getting trampled or drowned.

It’s then that the music, seeming to have gone,

glides through the reeds on its sinuous way.

The warm folds of forgetfulness

are meant to be comforting:

but how soon they cease to soothe us,

haunted as we shall always be

by the absent music, the departing hand.

And though we are not its destination,

neither are we bystanders happening along the path.

We are neither forgotten nor remembered,

but somehow have been included:

we know that for us it always comes to good

and that must be enough.

At the end of Grahame’s Pan chapter, Rat is trying to articulate what they have sensed and lost. It is a powerful description of the poetic project, which is why the episode is beloved by poets like Norman (and also my father):

`It’s like music — far away music,’ said the Mole nodding drowsily.

`So I was thinking,’ murmured the Rat, dreamful and languid. `Dance-music — the lilting sort that runs on without a stop — but with words in it, too — it passes into words and out of them again — I catch them at intervals — then it is dance-music once more, and then nothing but the reeds’ soft thin whispering.’

`You hear better than I,’ said the Mole sadly. `I cannot catch the words.’

`Let me try and give you them,’ said the Rat softly, his eyes still closed. `Now it is turning into words again — faint but clear — Lest the awe should dwell — And turn your frolic to fret — You shall look on my power at the helping hour — But then you shall forget! Now the reeds take it up — forget, forget, they sigh, and it dies away in a rustle and a whisper. Then the voice returns —`Lest limbs be reddened and rent — I spring the trap that is set — As I loose the snare you may glimpse me there — For surely you shall forget! Row nearer, Mole, nearer to the reeds! It is hard to catch, and grows each minute fainter.

`Helper and healer, I cheer — Small waifs in the woodland wet — Strays I find in it, wounds I bind in it — Bidding them all forget! Nearer, Mole, nearer! No, it is no good; the song has died away into reed-talk.’

`But what do the words mean?’ asked the wondering Mole.`That I do not know,’ said the Rat simply. `I passed them on to you as they reached me. Ah! now they return again, and this time full and clear! This time, at last, it is the real, the unmistakable thing, simple — passionate — perfect — — ‘

`Well, let’s have it, then,’ said the Mole, after he had waited patiently for a few minutes, half-dozing in the hot sun.

But no answer came. He looked, and understood the silence. With a smile of much happiness on his face, and something of a listening look still lingering there, the weary Rat was fast asleep.

Poetry strives to express the inexpressible. And while it never entirely gets there, it gets as close as language ever does.