Summer Weekly Food Series

My colleague Jennifer Cognard-Black, author of a forthcoming anthology of food literature (Words Rising: The Making of a Literary Meal) last September gave a talk for Museum Studies Week on food texts in the American colonies. The talk was sponsored by Historical St. Mary’s City, the reconstruction of Maryland’s 17th century capital that abuts our campus.

Jennifer notes that food, being perishable, presents museums and historians with a challenge. To study what and how people ate, we must look for related artifacts, including written ones. While these can take the forms of novels and poems (“foodie fiction” is becoming a genre of its own), in her talk Jennifer uses her skills of rhetorical analysis to examine written recipes.

By Jennifer Cognard-Black, English Dept., St. Mary’s College of MD

In 1635, a pamphlet entitled A Relation of Maryland was published as a means of encouraging more British citizens to emigrate to the relatively new colony of “Terrae Mariae.” In addition to other sources, the pamphlet cribbed heavily from Father Andrew White’s Briefe Relation of the Voyage unto Maryland, which had been published the year before and was the first travel narrative written about this place where we are: namely Historic St. Mary’s City.

In 1635, a pamphlet entitled A Relation of Maryland was published as a means of encouraging more British citizens to emigrate to the relatively new colony of “Terrae Mariae.” In addition to other sources, the pamphlet cribbed heavily from Father Andrew White’s Briefe Relation of the Voyage unto Maryland, which had been published the year before and was the first travel narrative written about this place where we are: namely Historic St. Mary’s City.

A Relation of Maryland contains many pieces of information about the new colony, including the attractiveness of the country, its salubrious climate, the peaceful nature of the Piscataways (the Indians indigenous to this region), and comments about the abundant flora and fauna of the area, including native edibles such as “Strawberries, raspires, fallen mulberrie vines, acchorns, walnutts, [and] saxafras. . .[ all] in the wildest woods” (Jameson 45). In addition, the pamphlet gave specific directions to British “adventurers” about what they should bring along with them for a trans-Atlantic voyage to Mary Land, including apparel, household effects, arms, implements, and, of course, food.

In listing the “Provision for Ship-board,” the compiler of A Relation of Maryland itemizes the following:

Fine Wheate-flower, close and well packed, to make puddings, etc. Clarret-wine[,] burnt. Canary Sacke. Conserves, Marmalades. . ., and Spices. Sallet Oyle. Prunes to stew. Live Poultry. Rice, Butter, Holland-cheese. . ., gammons of Bacon, [and] Porke. . ., Beefe packed up in Vinegar, some Weather-sheepe. . ., [and] Leggs of Mutton minced, and stewed, and close packed up in. . .Butter, in earthen pots. . . . [etc.]

What we know in part, then, about the first colonists to Maryland is that they had “mutton mouths”—by which I mean that they brought with them many of the British foods (including mutton) that they were familiar with in hopes of starting new flocks and herds as well as planting their culinary staple, wheat (which, as it turned out, didn’t grow particularly well in the New World).

And yet, if we were to try to establish a Colonial Food Museum to display burnt “Clarret-wine” or “Sallet Olye” or “Bacon gammons,” we would have a hard time of it. Food is ephemeral. It grows. It ripens. It rots. And while we might be able to stew a few prunes and make a wheel of Holland-cheese and lacquer the hell out of them so that they could be viewed by museum-goers, unless we were willing to replace the food objects within our exhibit fairly often, eventually our display would—in the words of an eighteenth-century recipe-writer, Jonas Green—become “ever so stinking.

So how do we represent the history of food in the context of museums and archives? Museums and archives, after all, are dependent upon material culture: the only way to preserve human memory is through keeping objects that somehow fix and contain some aspect of human experience. And when it comes to exhibiting human foodways, the archivist or the curator is bound by the problem of the “butter body.” For bodies are the true museums of food; we all incarnate the histories of our collective dinners—be they student dining room stir-frys or local pizzas or “Leggs of Mutton minced, and stewed, and close packed up in…Butter.”

Of course, archivists and curators get around the “butter body” problem by looking to the vast material culture that food is dependent upon for its production, preparation, and consumption. Thus, we see displays of farm or kitchen technologies in various history museums, such as the famous Julia Child Kitchen which has been on view at the Smithsonian since 2001. Or we have exhibits that relate food to place and space, such as this summer’s controversial Frito-Lay Farm Tour, which included a mobile greenhouse “potato gallery” designed to introduce a rural experience to urban dwellers, with some of Frito-Lay’s own potato-chip farmers on hand to answer questions.

Or there are foundations that create living history museums where food cultivation, preservation, and preparation is observable in an on-going and dynamic format. A close-by example are the gardens at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello in Virginia, where Jefferson’s own techniques are still used to grow 250 varieties of vegetables on site, including species that he himself brought back from France, Italy, and Mexico and other heirloom varieties that he developed through cross-pollination. (An heirloom seed itself might be thought of as a kind of museum: a bit of genetic memory brought back into the “now” through planting and harvesting.)

Still yet another means of preserving food and cookery is to collect texts that contain various forms of food writings. As an English teacher and scholar, I’m most interested in these culinary records. While there are many rhetorical forms that fall under the designation of “food records” or “food writing”—

–from menu poems

–to cookbook memoirs

–to foodie fictions like Fried Green Tomatoes

–to cookbooks themselves

—perhaps the most fundamental food text is the recipe.

The Recipe

Whether written on notecards, published in cookbooks, or posted on-line, recipes articulate food cultures and contain food memories. The recipe is a documentation of food traditions, where culture and history are transmitted as well as transformed—as practices of sharing, preparing, and eating food that both create and convey human interaction.

The recipe reveals that food and foodways are both elastic and contradictory. For instance, a recipe can symbolize birth or death. Not only can it be a record of a cake made for a christening or potatoes prepared for a funeral, if the recipe itself was written by someone who is now dead, when the text is followed and the dish is prepared, that deceased author lives again in Scottish scones warm and waiting on a plate.

A recipe also can represent the natural as well as the artificial—just think of the difference between a home-grown ingredient such as a peach and a peach-pie recipe calling for the use of what Michael Pollan has dubbed a “foodlike substance,” such as artificial vanilla extract made in a lab by a “flavorist.

Indeed, a recipe can convey health and poison, war and peace, surfeit and hunger, art and commodity. Recipes are multifaceted in terms of their content, and yet they’re also complex in their purpose—thus reflecting the intricacies of the cooks and eaters who use and enjoy them.

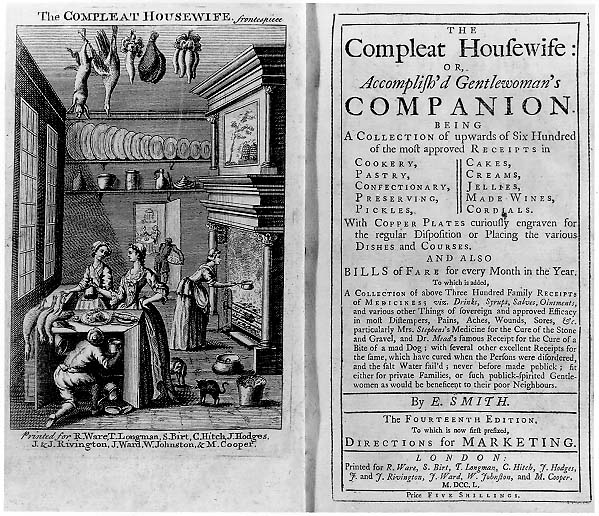

In North America, the first published recipes appeared in cookbooks such as Eliza Smith’s 1742 Compleat Housewife, believed to be the first cookbook printed in America, although it was written by an English author. The first American-written cookbook was by Amelia Simmons in 1796, who published a book entitled American Cookery, or the Art of Dressing Viands, Fish, Poultry and Vegetables, and the Best Modes of Making Pastes, Puffs, Pies, Tarts, Puddings, Custards and Preserves, and all kinds of Cakes, from the Imperial Plumb to the Plain Cake, Adapted to this Country, and all Grades of Life. Whew!

Simmons, a domestic worker herself and so a woman who had first-hand knowledge of cookery, was interested in producing a book specifically for a Colonial audience—with attention paid to American tastes, ingredients, and necessities. Originally self-published, the book was inexpensive, selling for only two shillings, three pence—a price which, as modern-day editor Mary Wilson points out, “justified its purchase even in homes where the family income would permit the buying of little printed matter besides the yearly almanac.”

What is of great interest in the Simmons book is how she truly attempted to adapt recipes “to this Country”—including five “receipts” using corn meal, the inclusion of a “Pompkin” pudding (what we would now recognize as “pumpkin pie”), still another “receipt” for “brewing Spruce Beer,” and the inclusion of the “Jerusalem artichoke” among the book’s “Directions for…Procuring the Best Viands, Fish, & c.”—a North American root vegetable that Julia Child would dedicate no less than twelve pages to in her 1961 classic, Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

The Simmons’ “receipts” don’t look much like recipes we see in modern cookbooks, although they do have certain elements that define the genre and create an idea about what is meant by eighteenth-century “cookery.” For instance, the Simmons’ recipe for “Pompkin pudding” is structured in terms of offering two variations (labeled “number 1” and “number 2”) and starts with a list of ingredients (notably an artery-clogging “9 beaten eggs”), then adds a few spare instructions on how to prepare said ingredients (by “crossing” and “chequering” the dough), and finishes with precise information on how to bake the pudding (“in dishes [for] three quarters of an hour”).

This form reveals that Simmons’ readers were Enlightenment thinkers: they appreciated a rational, “how-to” approach that utilized a specialized language (“stewing,” “straining,” “beating,” “crossing,” and “chequering”) to distinguish this text as one that fits the cultural category of “Colonial kitchen.”

Yet beyond the recipe’s form, if I were to work with this piece of writing in the context of one of my own Books that Cook classes, I would ask students to consider how this “receipt” for “Pompking Pudding” is expressing traditional femininity through its voice; is embedding technologies that already complicate distinctions between “homemade” and “manufactured” foods; is relying on spices that reveal an imperial economy; and is appropriating a Native American method for baking squashes into pie-like breads. As a cultural symbol—and one that eventually becomes a metonym of American nationhood as part of a Thanksgiving dinner—this brief eighteenth-century recipe for a pumpkin pie is conveying a tremendous amount of cultural context: the kinds of knowledge articulated by museums.

Yet a curator at a Recipe Museum wouldn’t want to limit herself to culinary information found in published sources, for in addition to “public” recipes such as Simmons which are printed in mass-market cookbooks, of course there are also “private” recipes kept by individuals on index cards, in commonplace books, and (increasingly) on computers as part of personal cooking files (mine is called “Sweet & Savory Stuff for Summer” since I never seem to have time to try new recipes during the year). Moreover, private recipes carry the distinction of being unique objects—one-of-a-kind artifacts that museum curators tend to prize.

Jennifer has also authored “The Feminist Food Revolution” (Ms Magazine, Summer 2010) and “Books that Cook: Teaching Food and Food Literature in the English Classroom” with Melissa Goldthwaite (College English, Winter 2008). A description of the “Books that Cook” course she teaches at St. Mary’s can be found here.

Go here to subscribe to the weekly newsletter summarizing the week’s posts. Your e-mail address will be kept confidential.

2 Trackbacks

[…] gave me the idea for the series in the first place. (See her earlier posts on the subject here and here.) Jennifer is allowing me to run an excerpt from the introduction to a book that she is co-writing […]

[…] is my colleague Jennifer-Cognard Black, who has contributed posts to this blog in the past (here and here). A number of the authors included in the book were there to read from their work. What […]