Wednesday

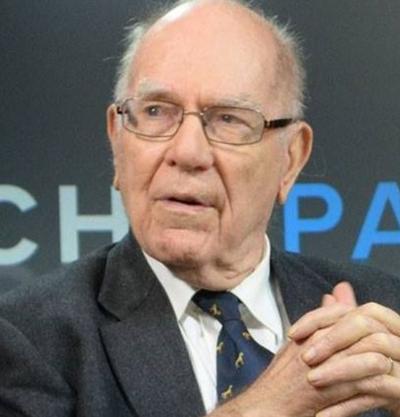

Here’s a story that most people missed but that registered with me: Lyndon LaRouche died last week at 97. I was never a “LaRouchie,” but for a few months as a graduate student I took his ideas seriously. That’s until I discovered he was a fanatic.

I learned about LaRouche from a friend who had friends who were followers. Intellectuals who operated at a higher level than I did—one a scholar and poet, one a scholar and musical composer—they liked the weight he gave to art and ideas. As LaRouche saw it, intellectual forces either advanced or retarded history.

I still have the issue of Campaigner, LaRouche’s publication, where he sets forth his view of intellectual influence. Entitled “The Secrets Known Only to the Inner Elites,” the article argues that all of Western history can be seen as a battle between two groups, one originating in Socrates and Plato, the other in Aristotle. As LaRouche puts it,

Through three millenia of recorded history to date, centered around the Mediterranean, the civilized world has been run by two bitterly opposed elites, the one associated with the faction of Socrates and Plato, the other with the faction of Aristotle. During these thousands of years, until the developments of approximately 1784-1818 in Europe, both factions’ inner elites maintained in some fashion an unbroken continuity of organization and knowledge through all of the political catastrophes which afflicted each of them in various times and locales.

In LaRouche’s mind, Plato the idealist is good because he has an expansive utopian vision while Aristotle the empiricist is bad because he chops everything into pieces. Every intellectual and artist is either an idealist or an empiricist and is to be judged accordingly.

I won’t go into detail about how all this works because it becomes a bit of a bore. The autodidact LaRouche may be widely read—he cites philosophy, intellectual history, literature, the arts, political science, economics, mathematics and other disciplines—but he reductively fits everyone into one of the two camps. It’s a bit like choosing up sides, putting those you like on one side and those you don’t on the other. I include just a smattering of LaRouche’s likes and dislikes below:

Likes: Homer, Aeschylus, Socrates, Plato, Euclid, Alexander the Great, Paul of Tarsus, St. Augustine of Hippo, Bruno, Galileo, Descartes, Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare, John Milton, Rembrandt, Oliver Cromwell, John Winthrop, William Penn, Benjamin Franklin, George Washington.

Dislikes: Aristotle, Ptolemy, Emperor Justinian, Thomas Aquinas, Luther, Calvin, Ignatius Loyola, Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Isaac Newton, David Hume, Adam Smith, Jeremy Bentham, Woodrow Wilson.

I wanted so badly to think that philosophy and the arts could have a tangible impact on history that I read LaRouche’s journal and also his book Dialectical Economics. No one else I had encountered talked this way. Here’s a sampling from the “Inner Elites” article, which pulls no punches:

It is relevant to all these points [Bruno’s support amongst such British figures as Sidney, Shakespeare and others] that Christopher Marlowe wrote Doctor Faustus in behalf of an effort to rescue Bruno from the Guelph Inquisition, and that English Tudor poetry, drama and music were based on the Platonic dialogue as a method, a matter in which Bruno’s influence was direct and potent.

Bruno of the late sixteeth century is the key, common link for all humanist networks of the seventeenth century. As such, he is the dominant figure of that period…

In England, more broadly, than just among those figures cited, his orbit was known as the “Italians,” a circle to which William Shakespeare was junior…

Directly opposite to Bruno and his allies in England was the evil Cecil, and Cecil’s appendage, the evil Francis Bacon. Elizabeth I vacillated…After the wretched Essex affair, the balance was tilted badly. With the accession of the wretched Stuart, James I, and James’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, Francis Bacon, an inquisition was launched against the humanists, the English economy was set back, and the circumstances leading to the belated beheading of Charles I set into motion.

For LaRouche, it’s not just that people are influenced by ideas. There are actual cabals at work, both for good and for bad. Once I realized LaRouche thought this way, I started to pull back. He sounded too much like a whacko conspiracy believer.

My misgivings were confirmed when I met a LaRouchie at a book fair. After I expressed interest, I was greeted with a three-hour monologue that was free of any self-doubt. At that point I had had enough.

I noted, however, whenever LaRouche showed up in the news, as he occasionally did. Initially Marxist, LaRouche became increasingly associated with conservatives as he embraced unfettered development. His followers in airports would display such signs as “nuclear reactors are better built than Jane Fonda.” They proclaimed nuclear fusion as the energy source that would save the world.

Then a LaRouchie won a Democratic primary somewhere in Illinois, prompting the Democratic Party to disavow him (the opposite of what happened with David Duke in Louisiana). Then LaRouche and some of his followers were jailed for credit card fraud, and he slipped from my mind. Until last week’s news, I hadn’t thought about him for years.

How can I excuse my brief flirtation other than to say that I was young and desperate for proof that intellectual ideas can have a tangible impact on world events?

I’m still looking for evidence. I’m more cautious about my fellow travelers, however.