Wednesday

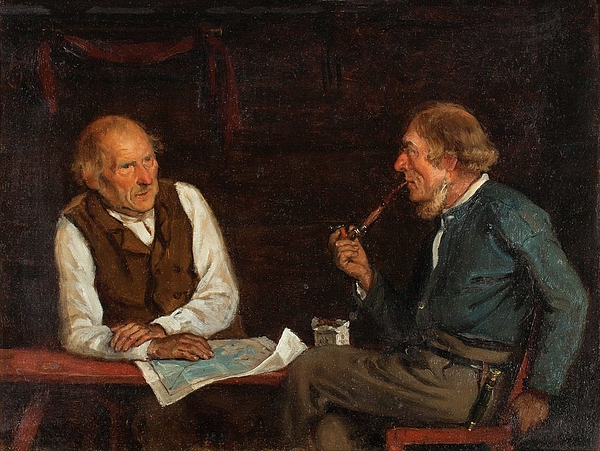

I write this post after having returned from a dinner with my old Slovenian friend Mladen Dolar, who I got to know when first visiting Slovenia (then Yugoslavia) in 1987 and have stayed friends with ever since. Since we hadn’t seen each other for ten years or so, we talked for seven hours, the last three hours in a restaurant featuring traditional Slovenian cuisine. Although trained as a philosopher, Mladen regularly teaches literature, so we did a version of Yeats’s conversation in “Adam’s Curse”:

We sat together at one summer’s end,

That beautiful mild woman, your close friend,

And you and I, and talked of poetry.

For instance, Mladen described the course he taught recently about Modernism to University of Chicago graduate students in the German department. The course focused on Kafka, Freud, and Samuel Beckett. Mladen sees Kafka representing the beginning of modernism and Beckett the end and believes that Beckett is more complex than people think.

Mladen describing his course grew out of a discussion we had been having about American politics. With each of the past three Republican presidents, he said (excluding H.W. Bush), we thought that things couldn’t get any worse, and in each case they did. I responded with Edgar’s quotation in King Lear upon encountering his recently blinded father: “And worse I may be yet: the worst is not/So long as we can say ‘This is the worst.” Mladen replied that he had just taught Beckett’s Worstward Ho, which draws its title from the line.

At another point in the evening, Mladen told me a fascinating story about his father’s run-in with an old Stalinist in the early 1950’s, a few years after Tito had broken with the Soviet Union. Mladen’s father was heading the theater in Maribor and had somehow gotten away with staging works by the French existentialists Camus and Sartre. So far, so good. He got into trouble, however, when he staged a play by 18th century French playwright Marivaux, who the French had rediscovered. Suddenly Dolar was challenged about why the workers should pay for a play written during the ancien regime. Uninterested in fighting such a fight, especially with a man who had been imprisoned horribly by Tito, Dolar left the theater for the national library.

While the attacks on his father’s artistic choices were unfortunate, Mladen and I both agreed that there is something positive about people finding a work so powerful that they feel the need to ban it. At least they take such works seriously. Mladen, who has written important books on “the voice” and on opera, is fascinated by those instances when riots have broken out over dramatic moments in music history, as they did when Stravinsky introduced Rite of Spring and Schoenberg the 12-tone scale. Regular readers of this blog know that I light up whenever I encounter such moments in literary history.

This led to a conversation about Plato banning poets from his ideal republic. Since I am writing about this in my current book project, I jumped at the chance to query an actual philosopher on my reading of Plato. Did Plato really believe, for instance, that Hesiod’s account of quarreling gods and Homer’s description of the underworld (also of Odysseus feasting) would corrupt young men?

Mladen agreed that Plato’s attacks on Greek myths and Homer are startling but noted that, unlike the reasonable Aristotle, Plato periodically tries out over-the top-ideas. For all of Plato’s suspicion of passion, Mladen said that deep passions often drive his work.

I said this makes a lot of sense when one looks at his interactions with Homer. Plato’s Socrates may decry the influence of Homer, but he himself knows Homer so intimately that he can quote long passages. I was reminded of Wayne Booth’s observation that, to truly understand a work, we must surrender to it—but that once we do, we are vulnerable to whatever influence it can wield. What if Plato is suspicious of Homer because, when engaging with Iliad or Odyssey, he feels himself not in control.

Mladen detected a certain “panic” in Plato, and that struck me as right, especially when I think of how, in Ion, Plato compares people caught up in artistic inspiration to mad Dionysian revelers. The word panic stems from the great god Pan, the Roman version of Dionysus. Mladen noted that Plato prefers the sedate lyre of Apollo to the maddening pan pipes of Dionysus.

I shared my own observation that, throughout the ages, literature’s power to immerse us in its world has both enthralled and frightened people. Christian parents might not attack Harry Potter were young people less passionate about it.

At another point, we talked about Shakespeare’s problem plays, and Mladen alerted me to Peter Gross’s Shylock, which looks at how Merchant of Venice has been staged through the ages, including by German Nazis. This after I described a staging of the play that made me sick to my stomach (but in a good way) over the mob hounding of Shylock.

And then we talked about important work that Mladen is doing on Sophocles’s Oedipus at Colonus, which he convincingly said works as a sequel to King Lear.

And so we talked on into the evening. Of course, we had to bring each other up to date on our families and our careers. But the deep dive into ideas is lifeblood to intellectuals, and I realized how starved I have been for a kindred soul with whom to have such a talk.