Spiritual Sunday – First Sunday in Lent

Lent is a time when, taking my cue from poet priest Malcolm Guite, I immerse myself in an extended work of poetry. Guite says that Lent is a good time for poetry since, through poems, we can arrive at “clarification of who we are, how we pray, how we journey through our lives with God and how he comes to journey with us.” Guite draws on Seamus Heaney and Samuel Taylor Coleridge to make his point:

Lent is a time set aside to re-orient ourselves, to clarify our minds, to slow down, recover from distraction, to focus on the values of God’s Kingdom and on the value he has set on us and on our neighbours. There are a number of distinctive ways in which poetry can help us do that…

Heaney spoke of poetry offering a glimpse and a clarification, here is how an earlier poet Coleridge, put it, when he was writing about what he and Wordsworth were hoping to offer through their poetry, which was

“awakening the mind’s attention to the lethargy of custom, and directing it to the loveliness and the wonders of the world before us; an inexhaustible treasure, but for which, in consequence of the film of familiarity and selfish solicitude, we have eyes, yet see not, ears that hear not, and hearts that neither feel nor understand.”

In the past, I have spent various Lents reading the collected poetry of George Herbert, John Milton’s Paradise Regained, the religious poems of T. S. Eliot, and Dante’s Paradiso. This year I am immersing myself in Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene.

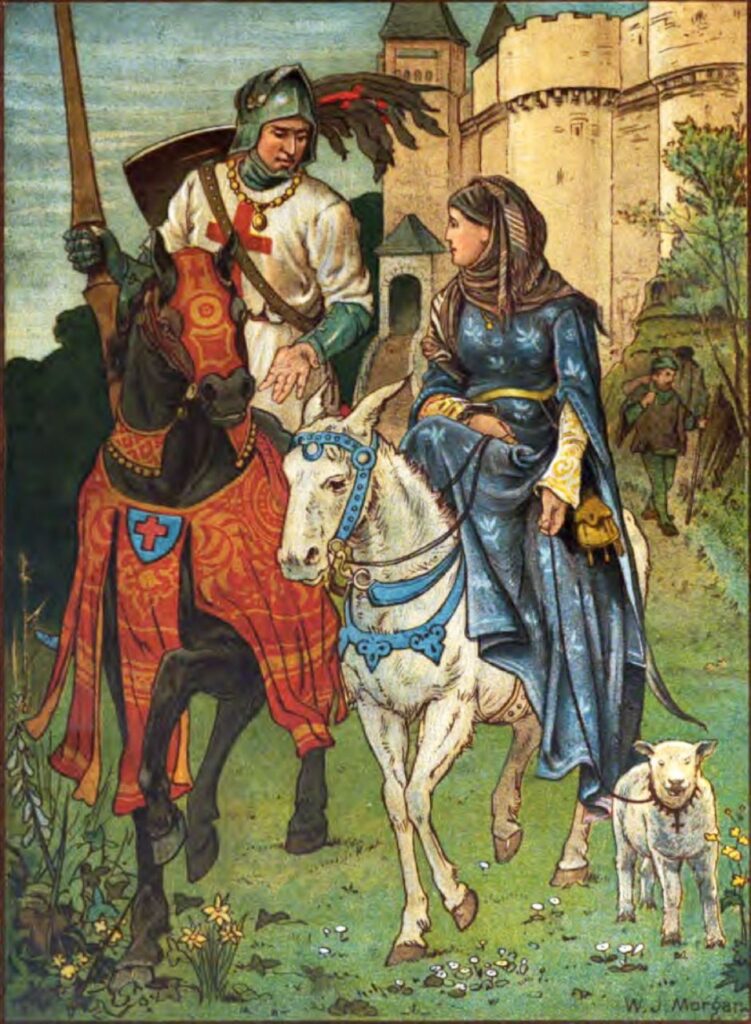

I’ve just been introduced to Red Cross Knight, whom Spenser, purposely using an archaic form of English to sound like Chaucer from 200 years earlier, describes as follows:

And on his brest a bloudie Crosse he bore,

The deare remembrance of his dying Lord,

For whose sweete sake that glorious badge he wore,

And dead as living ever him ador’d:

Upon his shield the like was also scor’d,

For soveraine hope, which in his helpe he had:

Right faithfull true he was in deede and word,

But of his cheere did seeme too solemne sad;

Yet nothing did he dread, but ever was ydrad.

Like Dante, Red Cross (along the Lady Una, who stands for the one true Church and whose cause he has taken up) finds himself lost in a dark wood and will soon be battling the monster Error:

They cannot finde that path, which first was showne,

But wander too and fro in wayes unknowne,

Furthest from end then, when they neerest weene,

That makes them doubt their wits be not their owne:

So many pathes, so many turnings seene

That which of them to take, in diverse doubt they been.

The tangled wood of theology and disputed dogma is indeed daunting, so that even the most well-intentioned souls can find themselves lost. I’ll report from time to time on how Spenser’s various adventurers handle it. Stay tuned.