Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share it with anyone else.

Thursday

Of all the Trump associates who are in legal trouble, I’ve been particularly fascinated by Peter Navarro, the former Trump advisor who was just convicted of defying a Congressional subpoena. Maybe it’s because he’s a former professor and I recognize in him some of the arrogance characteristic of certain academics, especially at research universities. Be that as it may, applying H.G. Wells’s Invisible Man to Navarro provides some insight into why Trump has been able to attract into his circle some supposedly intelligent people.

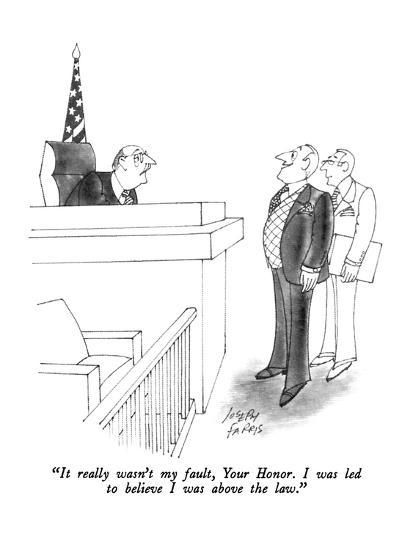

The above Joseph Farris cartoon also helps. In case you are reading this without the illustration, it features a well-dressed and supremely confident man informing a skeptical judge, “It really wasn’t my fault, your honor. I was led to believe I was above the law.”

Navarro is noteworthy for having proudly revealed “the Green Bay Sweep” on Ari Melber’s MSNBC show The Beat. The plan called for members of Congress to disrupt the counting of electoral votes so as to cause a historic delay. This, the plotters hoped, would get media attention and allow public pressure to build for then-Vice President Mike Pence to send electoral votes back to the six contested states. To which Melber responded, “Do you realize you are describing a coup?”

While Navarro may yet be held responsible for working to overturn the election, his recent conviction was for defying a subpoena from the Congressional committee investigating the coup. Arguing that Trump had granted him “executive privilege” (even though Trump has never confirmed this), Navarro declined to offer any defense or to call any witnesses. A jury quickly found him guilty, and he could face a year in jail and a $100,000 fine for each of the two counts against him.

Navarro has complained bitterly that the court costs and the fines are impoverishing him, but he could have avoided it all by simply showing up to the Congressional hearing. If he had decline to answer their questions, he would have faced no penalty (on the grounds of self-incrimination).

But to have done so would have meant acknowledging that he was answerable to another authority. I suspect the fantasy of thumbing one’s nose at the law with impunity may explain much of Trump’s popularity. Of course, the way that Trump articulates deep racial, ethnic, and sexual grievances is also part of his allure. But that’s a feeling that churns in the gut whereas defying rules and regulations gives one the sense that one can soar above earthly accountability.

Which brings me to Invisible Man, a work I’ve applied multiple times to Trump and other authoritarian figures. To revisit some of those ideas here, I’ve noted that Griffin describes a “feeling of extraordinary elation” when he realizes that people can’t see him. Confiding his history to his college friend Kemp, he says he immediately burned down the house where he made his discoveries so that others wouldn’t discover his secrets:

“You fired the house!” exclaimed Kemp.

“Fired the house. It was the only way to cover my trail—and no doubt it was insured. I slipped the bolts of the front door quietly and went out into the street. I was invisible, and I was only just beginning to realize the extraordinary advantage my invisibility gave me. My head was already teeming with plans of all the wild and wonderful things I had now impunity to do.

He uses the word “impunity” again further on:

Practically I thought I had impunity to do whatever I chose, everything—save to give away my secret. So I thought. Whatever I did, whatever the consequences might be, was nothing to me. I had merely to fling aside my garments and vanish. No person could hold me.

In the past, I’ve compared Griffin’s behavior to that of bad cops who bang suspects’ heads against car door frames (as Trump recommended), severely beat suspects, and sometimes shoot unarmed men. Griffin undergoes a similar trajectory, beginning with minor social infractions:

My mood, I say, was one of exaltation. I felt as a seeing man might do, with padded feet and noiseless clothes, in a city of the blind. I experienced a wild impulse to jest, to startle people, to clap men on the back, fling people’s hats astray, and generally revel in my extraordinary advantage.

With each action, Griffin becomes hungry for more, confirming the old adage that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. When Kent asks about “the common conventions of humanity,” Griffin replies that they are “all very well for common people.”

Griffin’s dark ambitions grow with his madness. Thinking he has successfully enlisted Kemp, he plots ways to wield total power:

“And it is killing we must do, Kemp.”

“It is killing we must do,” repeated Kemp. “I’m listening to your plan, Griffin, but I’m not agreeing, mind. Why killing?”

“Not wanton killing, but a judicious slaying. The point is, they know there is an Invisible Man—as well as we know there is an Invisible Man. And that Invisible Man, Kemp, must now establish a Reign of Terror. Yes; no doubt it’s startling. But I mean it. A Reign of Terror. He must take some town like your Burdock and terrify and dominate it. He must issue his orders. He can do that in a thousand ways—scraps of paper thrust under doors would suffice. And all who disobey his orders he must kill, and kill all who would defend them.”

Note that he uses one of Trump’s favorite words here: “dominate.” He’s prepared to use violence if necessary.

While I don’t know if I can attribute Griffin’s sadism to Navarro, some Trump followers feel as though he’s given them permission to act out their dark impulses. The thrill that comes with asserting your dominance over others is a sensation familiar to rapists.

But putting that aside, Navarro may have felt so exhilarated at thumbing his nose at Congress—something his idol has done regularly—that the rush overwhelmed common sense. What a sensation for someone who, all his life, has had to follow the rules.

To be sure, there’s another explanation for his behavior, something slightly more rational than an emotional Trumpian high. As John Stoehr of Editorial Board points out, Navarro may have just been making a calculated gamble, one that came perilously close to succeeding:

[Navarro] is where he is, because the plan failed. If it had succeeded, there’d be a Trump White House and a Trump Department of Justice. There’d be no accountability, “because I’m a Trump guy!”

Indeed, Navarro’s throw of the dice may still be rewarded if Trump is reelected, pardons him, and awards him a high position. Many Trumpists are convinced that their man will wipe the floor with “senile” Joe Biden.

Such gambles have succeeded in the past, as Steve Bannon well knows. Bannon, the Trump whisperer who will also be going to jail for defying a Congressional subpoena, points to figures like Lenin, Mao and Castro, who risked everything and came out on top. And they got satisfying payback as well.

This is why the court cases against Trump and his confederates are so important. Sometimes applying justice to a rich and powerful man can itself feel like a gamble, but the arrogance of Trump and his lawbreaking associates can only be stemmed if they are brought to justice. As it is, Trump is desperately attempting to taint the jury pool and to regain the pardon power that comes with the presidency. Wrestling with him can feel like wrestling with someone who is everywhere at once–that’s what it’s like to fight the Invisible Man at the end of Wells’s novel–but in the end the forces of good prevail.

Pray that our own story ends similarly.