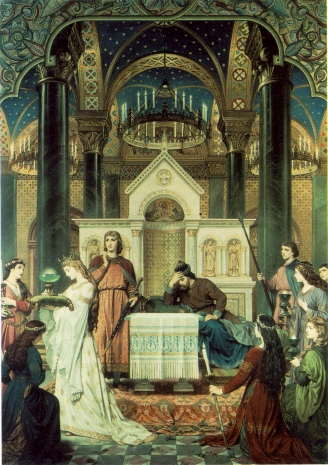

A. Spiess, “Parsifal in Montsalvat, the Castle of the Holy Grail”

I wrote last Thursday about neuro-lit, which an article in the New York Times has trumpeted as English’s “best new thing.” Certain practitioners are analyzing the way readers become absorbed in stories—fictional identification—by scanning their brains as they read. Practitioners of this new approach are contending that fictional identification has played a key role in the evolution of the brain.

Some of them are also contending that neuro-lit will “rescue literature departments from the malaise that has embraced them over the last decade and a half.” Here’s what one enthusiast has to say:

Jonathan Gottschall, who has written extensively about using evolutionary theory to explain fiction, said “it’s a new moment of hope” in an era when everyone is talking about “the death of the humanities.”

I don’t know who this “everyone” is, and as far as malaise is concerned, my department isn’t experiencing it. The excitement reminds me of one of the final scenes in David Lodge’s novel Small World: An Academic Romance, a campus novel that satirizes literary scholars.

Lodge’s novel alludes throughout to the Arthurian wasteland myth. In Chretien de Troye’s version of the myth, Percival, a knight of the Round Table, comes upon the “fisher king,” who has a wound that has rendered him impotent and turned his kingdom into a wasteland. At the banquet table Percival witnesses what proves to be the grail, but because he remains silent, the king and land remain infertile.

The hero in Small World is an English grad student named Persse McGarrigle. The world of literary studies is portrayed as a sterile affair where scholars hop from one international conference to another delivering the same worn-out lectures. The key figure in this world is Kingfisher, who may be modeled on one of the deconstructionist superstars (Jacques Derrida, Paul DeMan) who reigned in 1984 when Small World was written. The scene that I have in mind occurs at the end of the book when Persse is attending yet another deadly conference session, which is also to be the occasion where a prestigious “UNESCO Chair” will be awarded to a deserving scholar. As the panelists drone on, Kingfisher appears to get more and more depressed.

Unlike his Arthurian precursor, however, this time Persse does not remain silent. “What do you do if everybody agrees with you?” he asks the panelists during the question and answer session.

The question has never been asked before and everyone is stumped. Kingfisher, however, perks up and declares it a good question. Suddenly the room

erupted with a storm of applause and excited conversation. People jumped to their feet and began arguing with each other, and those at the back stood on their chairs to get a glimpse of the young man who had asked the question that had confounded the contenders for the UNESCO Chair and roused Arthur Kingfisher from his long lethargy. “Who is he?” was the question now on every tongue. Persse, blushing, dazed, astonished at his own temerity, put his head down and made for the exit. The crowd at the doors parted respectfully to let him through, though some conferees patted his back and shoulders as he passed—gentle, almost timid pats, more like touching for luck, or for a cure, than congratulations.

New life flows in the sterile wasteland of literary studies as the question promises to open up new lines of inquiry.

Will neuro-lit save literary studies from its wasteland malaise? Scholars are excited because it promises to give their field a new prominence. If it can be proved that a process fundamental to interpreting stories is also fundamental to evolution, then we literature folk can walk with an extra swagger.

The last time we walked with such swagger was during the 1980’s when the deconstructionists said there was nothing “outside of text” and that everything in culture can be interpreted the way a book can be interpreted. (If everything is a sign system, then English teachers will do well because we are good at reading sign systems.) Some of the ideas that came out of the deconstruction movement have become commonplace today. For instance, we frequently talk about politics as narrative, saying that politicians are successful to the extent that they can “control the narrative.”

I’m not unsympathetic with research English departments looking for “the next big thing.” Those people define themselves by the new ground they break, and some decades provide more exciting new territory to explore than others. The same thing occurs in all the disciplines. In the sciences for instance, sometimes physics is king, sometimes biology. (Currently, because of genetics, it is biology.)

By contrast, those of us teaching at small liberal arts colleges have the luxury of borrowing those ideas from the academic superstars that we like while ignoring the rest. Because we have students to teach who haven’t yet read Emma or King Lear, we have lots of exciting work to do. No malaise here.

For the record, I’m okay with the urge to find a biological basis to storytelling. If you look at my website’s mission statement, you will see that I claim that literature is as foundational to our lives as food or shelter. I could use the new research as added proof.

After all, if I can point to scientific studies that say we are hardwired for stories, then my claim takes on an extra credibility. So by all means, literary scholars should look into the biology of literature.

But neuro-lit will have limited application. Practitioners of neuro-lit are not going to open as many new insights into works as did, say, feminist or post-colonialist or reader response theories did. In fact, as far as I can tell, they are going to have little to say about individual works of literature, just literature as a whole. Even if the brain did scan differently for a Shakespeare play than it did for a Jane Austen novel, I’m not sure we would get anything very meaningful out of the contrast.

In short, neuro-lit is no Galahad, and those English Departments that are in a fisher king funk may have to keep waiting for a savior.

2 Trackbacks

[…] Pippin is particularly critical, as I have been, of those who try to turn literary criticism into an actual science. Check out my two critiques of neuro-lit here and here […]

[…] I’ve written a couple of times (here and here), I’m not enamored with neuro-criticism because I don’t think it adds much to an understanding […]