In Saturday’s post I predicted that our Commencement ceremony would feature a reading of Lucille Clifton’s “the blessing of the boats (at st. mary’s).” As it turns out, a poem was read but my colleague Jeff Coleman instead chose to read the final section of Derek Walcott’s “Bounty.”

Before I comment on the Walcott poem, it’s worth noting why we read poetry at our graduations. Years ago we used to have a non-denominational prayer delivered by the rector from the Episcopal Church that abuts the campus. (Despite our name, St. Mary’s College of Maryland has no religious affiliation—we are named after St. Mary’s City.) But one year the rector upset a number of faculty by concluding his prayer with “in the name of Jesus Christ” (I remember a Jewish colleague particularly complaining). Couple that with the fact that the College was having a boundary dispute with the Church at the time and the prayer got dropped. For several years we sang “America the Beautiful” and then we evolved to Lucille’s poem. Now we choose any poem.

What I find of interest is the felt need for poetry, which now appears to have become a feature of presidential inaugurations as well. Matthew Arnold, who saw art as the successor to religion, understood how poetry performs a vital spiritual role in public life.

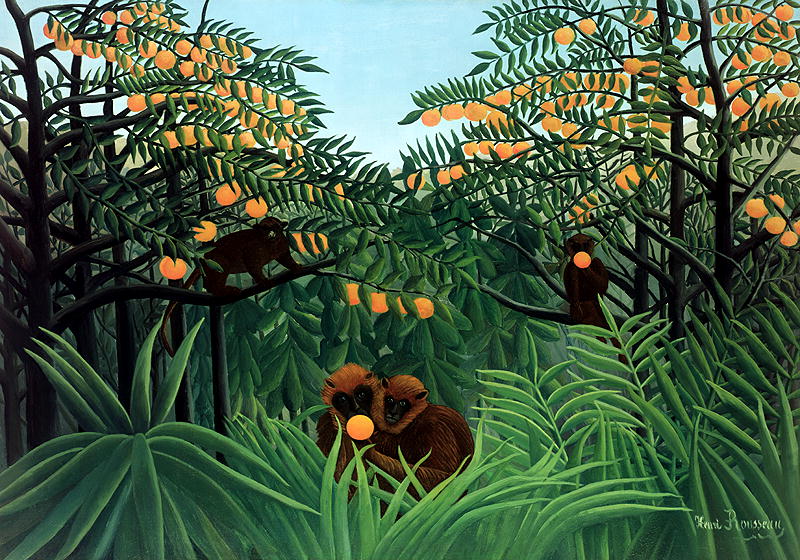

Back to Walcott’s poem, which proved to be appropriate given that it describes an Edenic landscape that is not unlike our own. We too have many of the creatures mentioned, such as crows, voles, otters, deer, squirrels, hares, crabs, and blackbirds. But no bears.

Introducing the poem, my colleague said he chose it several months ago. We were in the grip of an unusually cold and snowy winter and he was dreaming of spring.

Although “Bounty” is an elegy to Walcott’s mother, it works unexpectedly well as a graduation poem as students wave farewell to their alma mater–which is to say, their “fostering mother.” In the final section of the poem, Walcott says that we should not mourn his mother’s passing—or, we could say, students should not mourn leaving the college—but rather focus on this “bountiful day.” Gazing like those mad nature poets Tom O’Bedlam and John Clare upon the minutiae of nature, the poet says we must learn all that is to be learned from the bounty that is before us.

The bounty includes even the ants, whose long lines remind Walcott of his poetic “business and duty,” which is to write long lines of words. This is the “lesson you taught your sons,” he tells his mother: “to write of the light’s bounty on familiar things/that stand on the verge of translating themselves into news.”

The Bounty

By Derek Walcott

7

In spring, after the bear’s self-burial, the stuttering

crocuses open and choir, glaciers shelve and thaw,

frozen ponds crack into maps, green lances spring

from the melting fields, flags of rooks rise and tatter

the pierced light, the crumbling quiet avalanches

of an unsteady sky; the vole uncoils and the otter

worries his sleek head through the verge’s branches;

crannies, culverts, and creeks roar with wrist-numbing water.

Deer vault invisible hurdles and sniff the sharp air,

squirrels spring up like questions, berries easily redden,

edges delight in their own shapes (whoever their shaper).

But here there is one season, our viridian Eden

is that of the primal garden that engendered decay,

from the seed of a beetle’s shard or a dead hare

white and forgotten as winter with spring on its way.

There is no change now, no cycles of spring, autumn, winter,

nor an island’s perpetual summer; she took time with her;

no climate, no calendar except for this bountiful day.

As poor Tom fed his last crust to trembling birds,

as by reeds and cold pools John Clare blest these thin musicians,

let the ants teach me again with the long lines of words,

my business and duty, the lesson you taught your sons,

to write of the light’s bounty on familiar things

that stand on the verge of translating themselves into news:

the crab, the frigate that floats on cruciform wings,

and that nailed and thorn riddled tree that opens its pews

to the blackbird that hasn’t forgotten her because it sings.

The images of crucifixion in the final stanza may speak of the poet’s suffering over the loss of his mother. She appears to have taken time with her. But in focusing on the bounty of the day, he reminds us that, even in the sadness of departures, the song goes on. The thorn-riddled tree becomes a church for the blackbird, pointing to resurrection.

Just because my students go on to sing other songs, St. Mary’s will not be forgotten. We had them write long lines of words, and their experiences here will always reside somewhere within their singing.