Monday

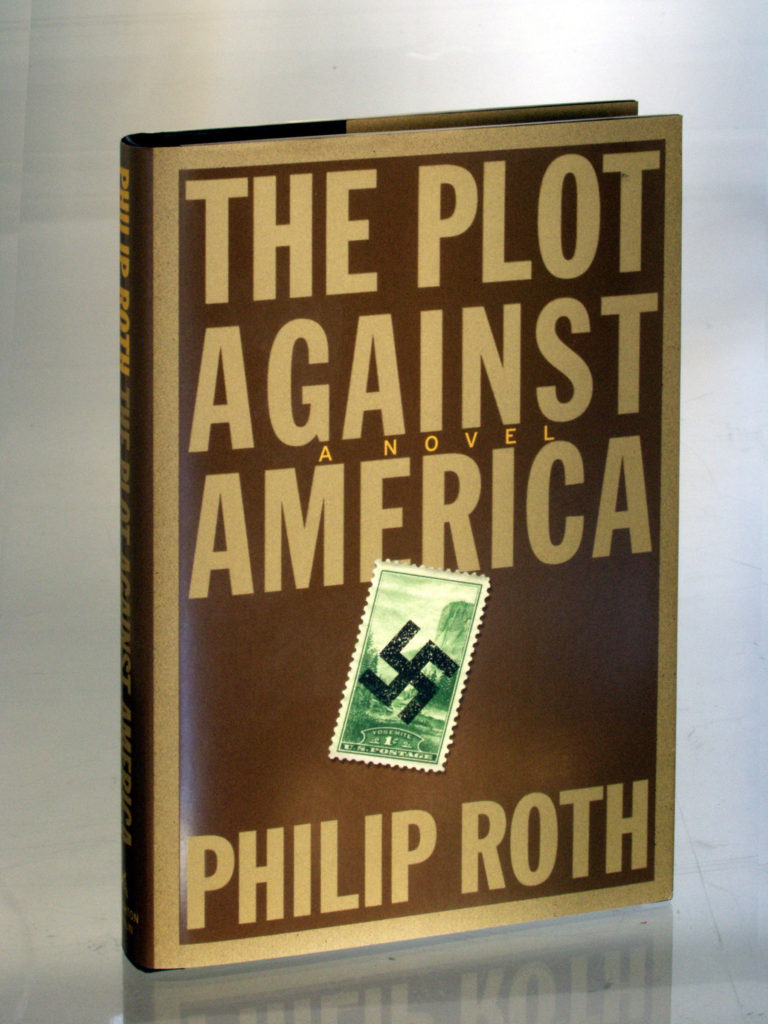

A few months before Donald Trump was elected president, Carlos Lozada of the Washington Post compared Trump’s rise to two novels about a fascist takeover of America, Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here (1935) and Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America (2004). I’m very impressed with how much the novels helped Lozada see clearly what a Trump presidency would look like.

If the novels are prescient, it’s because Lewis and Roth understand at a deep level the dark strain that has always been present in the American experiment. Although not everything the novels describe has come to pass, we also haven’t yet seen a second Trump term. We have not yet seen concentration camps (other than immigrant families in cages), a state takeover of the media (other than Fox News, where the relationship is more reciprocal), or executions (other than a few killings and attempted killings by rightwing terrorists and racist cops). I’m not confident, however, that we will avoid such a future in a second Trump term.

It Can’t Happen Here, Lozada notes,

features a populist Democratic senator named Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip who wins the White House in the late 1930s on a redistributionist platform — with a generous side order of racism — and quickly fashions a totalitarian regime purporting to speak for the nation’s Forgotten Men.

Just as Trump has Art of the Deal, so Windrip

has a best-selling book, Zero Hour — “part biography, part economic program, and part plain exhibitionistic boasting” — that is required reading among the faithful. The leader also delivers awful yet captivating speeches. Doremus Jessup, the aging, small-town newspaper editor and hero of Lewis’s novel, marvels at Windrip’s “bewitching” power over large audiences. “The Senator was vulgar, almost illiterate, a public liar easily detected, and in his ‘ideas’ almost idiotic.” But he captivates supporters, addressing them as if “he was telling them the truths, the imperious and dangerous facts, that had been hidden from them.”

Plot against America, meanwhile,

offers a similarly harsh vision of that era, imagining the slow implosion of a working-class Jewish family when the Republican Party nominates aviator Charles Lindbergh for the presidency in 1940. The victorious Lindy strikes a pact with Hitler, launches federal programs that break apart and resettle Jewish communities, and promotes anti-Semitic thuggery.

Lozada observes,

Much as Trump claims that only he is tough enough to restore national glory, in The Plot Against America Lindbergh is hailed as a “man’s man who gets the impossible done by relying solely on himself.” Republican Party leaders despair over Lindy’s refusal to take any of their wise advice on how to run his campaign. Defenders believe that Lindbergh’s strength of personality will enable him to strike deals — great ones, the best ones — with the world’s bad guys. “Lindbergh can deal with Hitler, they said, Hitler respects him because he’s Lindbergh.”

From reading Lewis in July, 2016, Lozada could foresee Trump’s relentless attack on the press, which was already well underway during the 2016 campaign:

Like Trump, Windrip works hard to discredit the journalists covering him. “I know the Press only too well,” he declares. “Almost all editors hide away . . . plotting how they can put over their lies, and advance their own positions and fill their greedy pocketbooks by calumniating Statesmen who have given their all for the common good.” As the novel progresses, Windrip detains them and takes over their publications, producing puff stories exalting the governing “Corpos,” members of the newly created American Corporate State and Patriotic Party.

Lewis also foresees how the GOP and others would underestimate Trump, thinking they could control him. In other words, they ignored Masha Gessen’s major maxim, “Believe the autocrat. He means what he says”:

That hope [that a president Trump would become presidential] recurs in the literature of totalitarianism. In It Can’t Happen Here, Jessup hears all the time that he needn’t worry. “You don’t understand Senator Windrip,” Jessup’s son Philip, a lawyer, lectures him. “Oh, he’s something of a demagogue — he shoots off his mouth a lot about how he’ll jack up the income tax and grab the banks, but he won’t — that’s just molasses for the cockroaches.” And the father believes it for a while, in denial even after Windrip imposes martial law. “The hysteria can’t last; be patient, and wait and see, he counseled his readers. It was not that he was afraid of the authorities. He simply did not believe that this comic tyranny could endure.”

Just as we have seen members of historically oppressed groups collaborating with this president (most notably the Jewish Stephen Miller and African Americans like Hermann Cain, Ben Carson, and those who vouched for Trump at the Republican National Convention), so we encounter collaborators in the two novels:

The editor’s in It Can’t Happen Here and the genial rabbi in The Plot against America make their choices, finding accommodation with their new leaders mainly out of self-interest. As Jessup grows radicalized in his opposition to Windrip, his son feigns concern, warning Jessup that he’s going to get into trouble if he keeps opposing local Dorpos. But soon Philip’s motive emerges: The government is offering him an assistant judgeship, he admits, and the appointment could suffer over his father’s intransigence. Rabbi Bengelsdorf, meanwhile, reaches the highest ranks of the Lindbergh administration, the token Jewish adviser, counseling the first lady and running the Office of American Absorption.

We also see an asymmetry in how people respond, with liberals far less likely to wield guns than the right—and even when they arm themselves, finding themselves pitted against the police in a way that rightwingers are not:

In The Plot Against America, a New Jersey Jewish community begins an armed self-defense patrol — the Provisional Jewish Police — which ends up clashing, fatally, not with anti-Semitic Lindbergh supporters but with local police. Herman, hiding with his family in a neighbor’s home as fighting stalks their block, declines to wield a gun. “I believe in this country,” he says simply.

The left also believes much more deeply that they will be saved by America’s institutions:

Trump feels like an American hallucination: wealth, sex, reality television, social media — he is every national fixation in excess. Yet, more than electoral college math or the Democratic nominee, what stands against his brand of politics is America itself, its self-perception and self-knowledge. That is what the fictional Roth family concludes in a visit to Washington, where they encounter anti-Semitic Lindbergh supporters but soak in the historic buildings and recite hallowed inscriptions on national monuments. “It was American history, delineated in its most inspirational form, that we were counting on to protect us against Lindbergh,” Herman’s youngest son decides.

So far, that faith is not entirely misplaced, with journalism, the judiciary, and the intelligence services holding firm. How much more pressure they can withstand is an open question, however.

Neither Lewis nor Roth include a major crisis like Covid-19. For that, one must turn to Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale, in which Christian extremists seize power following some kind of nuclear catastrophe. Our own version of this is the Trump administration using the pandemic to undermine the election, education, the post office, and social security (by attempting to end the payroll tax).

It Can’t Happen Here and The Plot to Save America are all the more disturbing, however, because they show one doesn’t need extraordinary circumstances to get a Trump. Unless having had a black president was an extraordinary circumstance.